The Pasvik River

One river - three states

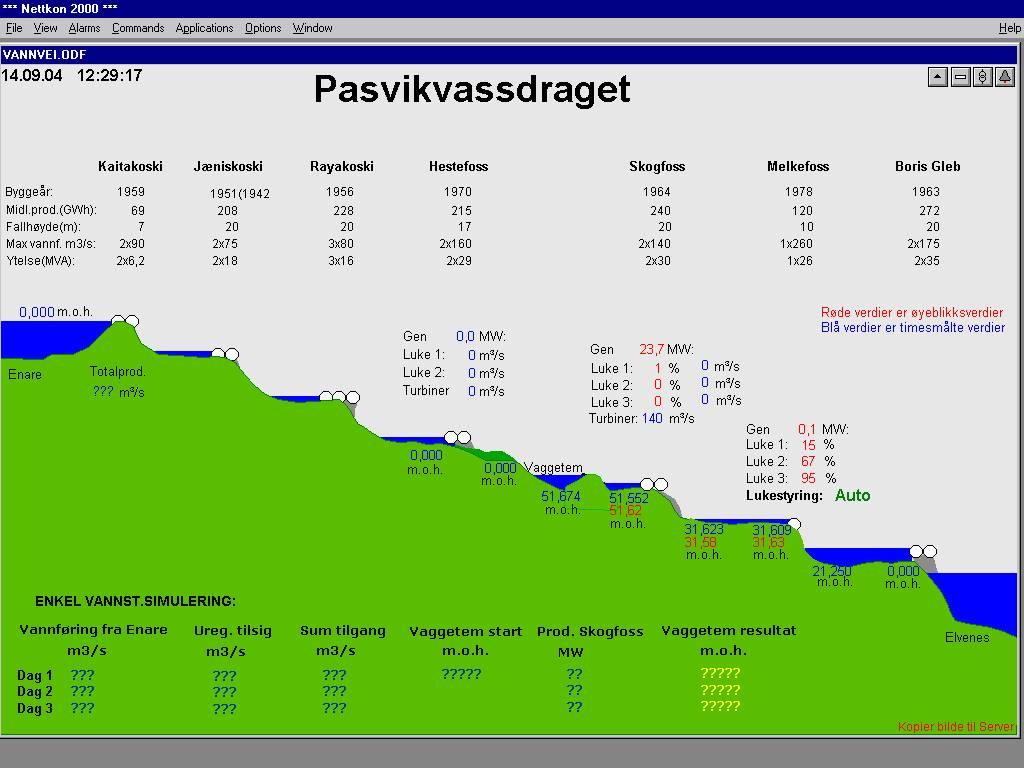

The Pasvik river flows from the Inari lake in Finland. The Pasvik river system has been developed with seven hydro-electric power stations, four of them along the Norwegian-Russian border. These four power stations were built during the Cold War, when Russia was the Soviet Union and relations between East and West were extremely cool. Norway and the Soviet Union nevertheless managed to co-operate well and closely on the Pasvik river development.

|

|

|

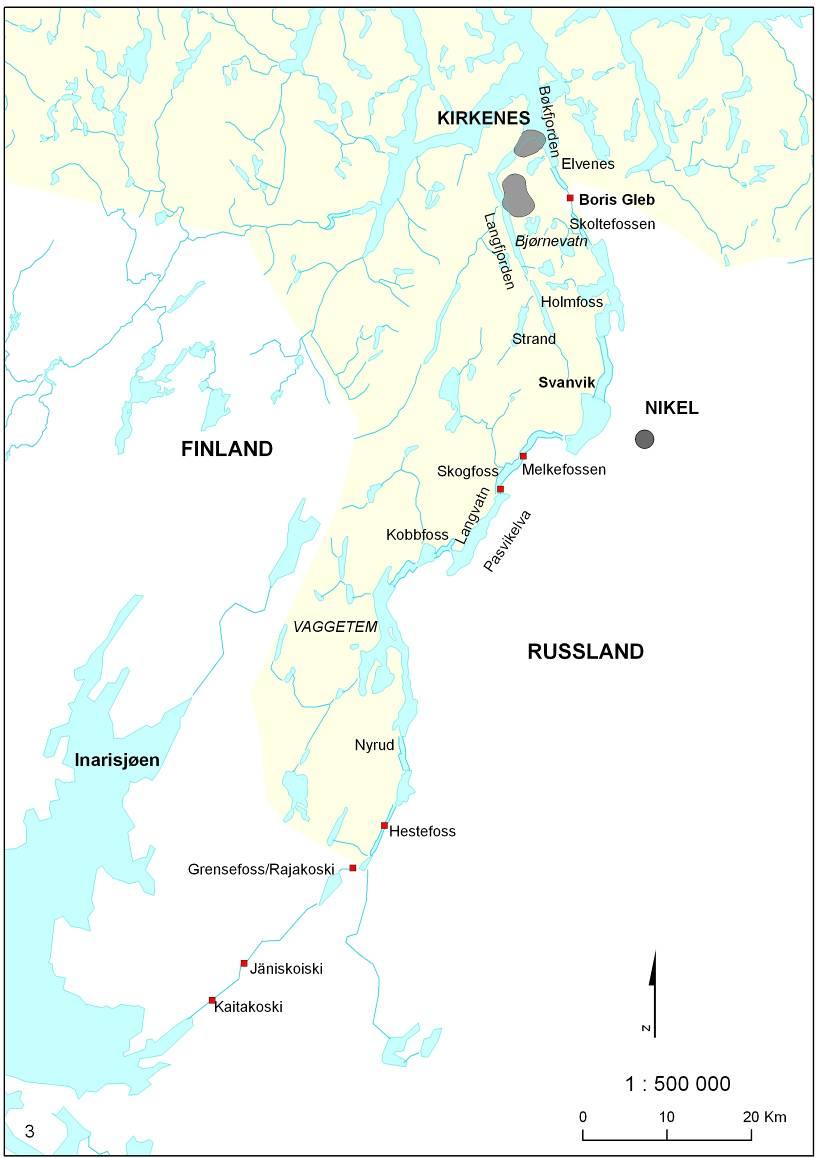

Today, the Pasvik river forms the border between Norway and Russia. The source of the river is the enormous Inari lake in Finland. There are in addition many smaller river systems flowing into the Pasvik river, which runs out into Bøkfjorden near Kirkenes. Russia has a total of five power stations on the river, while Norway has two. The power stations on the Pasvik river

Much of the work done on the Russian power stations at Hestefoss and Boris Gleb was carried out by Norwegian contractors. The two countries surrendered areas of land to one another in connection with the development of the Pasvik river. The collaboration on the development project between Norway and the Soviet Union went on during the Cold War. 1.4 TWh of hydropower are produced in the Pasvik river system, sufficient for as many as 55,000 households. Of this, the Norwegian share is 387 GWh, enough to provide power for 15,000 households.

The Pasvik riverToday, the broad Pasvik river flows peacefully through the Pasvik valley. It is not a steep river valley, but wide and relatively shallow. There are a few rapids left, whereas all the waterfalls have been developed. The fall in the river is very slight; Vaggetem, in the very south of the Pasvik valley, is only 51.7 metres above sea level. In many places the river is several kilometres wide. The border line between Norway and Russia largely follows the deepest channel in the bottom of the river. Biological diversityThe Pasvik river system is the life nerve in this far-flung forest landscape. The river, the lakes and the wetland areas provide a home for a great many fish, birds and animals. The area attracts a number of species of waterbirds such as ducks, geese, waders and whooper swans, and provides a landing place for several species of migratory birds. The river system is extremely rich in fish, and has the highest number of species, 15, on the entire North Calotte. The most common species are whitefish, perch, pike, vendace, grayling and trout. |

Hydropower regulationThe development of hydro-electric power stations and dams has caused a marked change in the character of the river system. Several waterfalls and rapids were eradicated with the regulation of the river, which has greatly reduced populations of otter and dipper birds in the main watercourse. In addition, the regulation has led to fish species like whitefish, perch and pike, which are lake-dwellers, taking over the territory of fish that thrive in fast-flowing rivers, such as grayling and trout. Life nerve and connecting linkThe Pasvik river has been the life nerve of, and of great importance for, the population of the valley down through the centuries. With its rich fish resources, the river was an important source of food. Traffic on the river was by river boat and ferry, and the river formed a vital traffic artery before the arrival of roads and motor vehicles. In winter, people drove sleighs on the ice-covered river, pulled by horses or reindeer. Today, the snow scooter dominates, while dog- or reindeer-drawn sleds and sleighs are used mostly for tourism. In the days when forestry was an important industry, logs were floated all the way down the river from Finland to Bøkfjorden. From unrestricted traffic to strict rulesIn the years before the Soviet Union became our neighbour, traffic was unrestricted and people would often row over the river to visit their neighbours on the other side. There was good contact between Finland and Norway, and some people found their sweethearts across the Norwegian-Finnish border. Today, it is not permitted to cross the border that runs in the river. The rules governing river traffic have been regulated through agreements between Norway and Russia. Although relations between Norway and our neighbours in the east have changed since the Soviet era, the rules governing traffic on the river are almost as strict as during the Cold War. There is only one official border crossing place between Norway and Russia − at Storskog, not far from Elvenes.

Ivalojoki. The river at Ivalo in Finland is one of several large rivers that run out into the Inari lake. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Inarijärvi (Inari lake), Finland’s third biggest lake at 1043 km². It is 50 km wide, 80 km long and 92 metres deep at its deepest point. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Autumn evening by the Pasvik river. The broad river flows slowly on its journey to the sea. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum))

The Inari lake and some of its 3,318 islands. The island of Ukonkivi is visible on the horizon. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

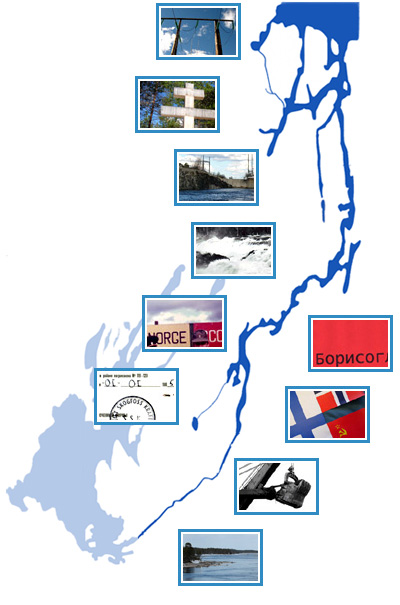

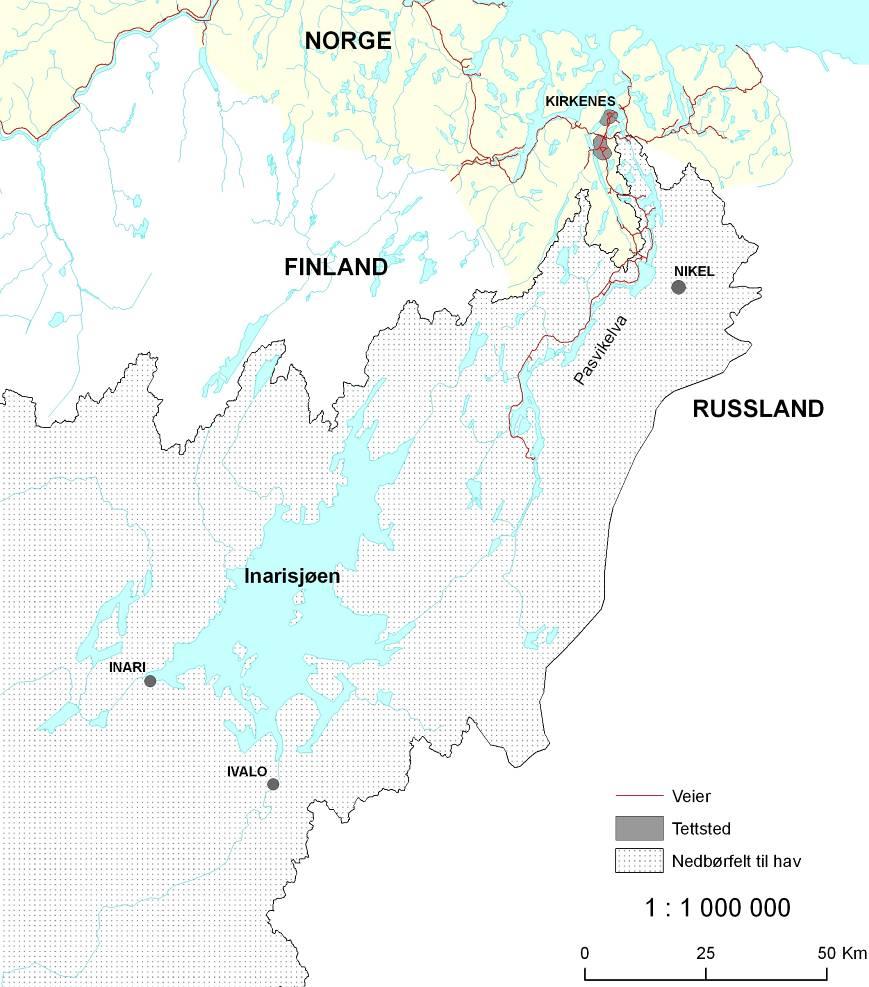

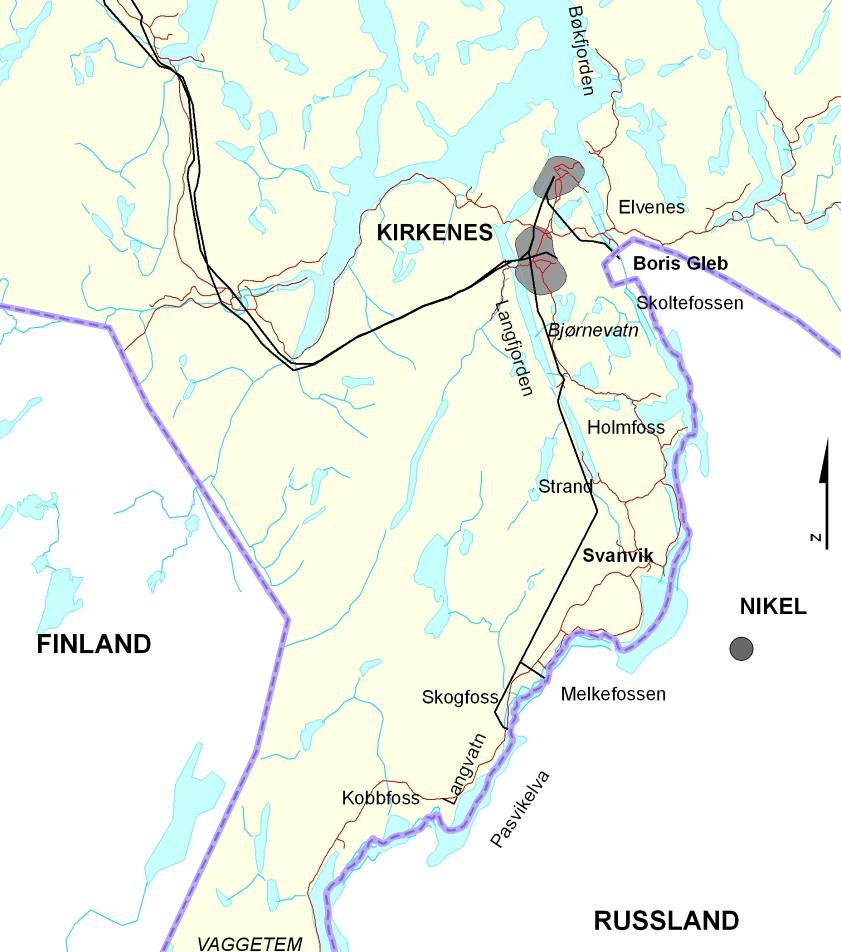

The water without borders – the Pasvik river. Red dots show the power stations along the river. The main watercourse measures 380 km. This includes the inflow to the Inari lake, Ivalojoki and its sources. Among Norwegian rivers only the Glomma is longer, at 617 km. From its source at the Inari lake the Pasvik river runs 140 km to Bøkfjorden near Kirkenes. 112 km of the river form part of the national border between Norway and Russia. (Map: NVE)

Parts of the Pasvik watercourse’s field of precipitation. The total precipitation field measures 18,344 km², most of which is in Finland and Russia. In Norway the precipitation field measures 1,044 km². Only the Glomma river has a larger field of precipitation than the Pasvik river. (Map: NVE)

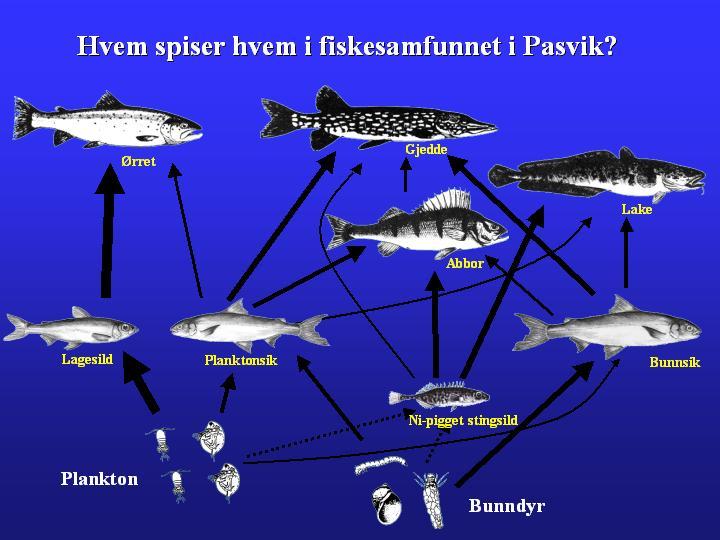

With 15 registered species of fish in the watercourse, the food chain has many levels. The most important species at the top of the food chain are trout, pike and burbot. Vendace is a new species that has become established in the watercourse. In only a few years it has become a dominant species, having a great impact on the original eco-system. Vendace competes hard for food with plankton whitefish and is also an attractive food for trout. (Illustration: Per-Arne Amundsen, Norwegian College of Fisheries Science)

Towards the end of April whooper swans arrive on the Fjærvann lake in Upper Pasvik. Fjærvann’s shallows are free of ice in the early spring, and here the birds can find food while waiting for the snow and ice to melt from their nesting areas. At the beginning of September the whooper swans gather again and begin their long journey south, to warm, ice-free areas. (Photo: Ragnar Våga Pedersen, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

The Pasvik river runs out in Bøkfjorden at Kirkenes. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum) |

|

The early 1900s saw the development of industry in Sør-Varanger with the establishment of the mining company Aktieselskapet Sydvaranger, and the population also grew dramatically in the ensuing decades. The new industrial works required a great deal of energy and it was necessary to start developing the river system to provide hydro-electric power. The power stations Tårnet Kraftverk and Kobbholm Kraftverk were built. The network of power lines was gradually expanded and in 1936 an interconnector was built up to Svanvik. Plans to collaborate on the development of the Pasvik river system were stopped by World War II. Ore findsIn 1866, Tellef Dahll was in North Norway to make a geological map of the area, and in Pasvik he discovered ore. The ore was very poor in iron, and with the technology of the time the iron could not be extracted. However, new inventions towards the end of the 1800s made it possible to extract the iron. Christian Anker, a merchant, was willing to invest money in the enterprise. Establishment of Aktieselskabet SydvarangerIn 1906, the mining company Aktieselskapet Sydvaranger (A/S Sydvaranger) was established, and was largely responsible for both the economic and cultural development of Sør-Varanger over the next 90 years. The mining activity started in 1907. Workforce numbers fluctuated in the first few years, partly because of extremely difficult climatic conditions. In 1910, mining operations started and the business was successful until World War I. The business led to a sharp increase in the population in Sør-Varanger, from 1,912 persons in 1900 to 4,800 in 1920. After World War I, there was a decline in the need for iron and in 1925 the company went bankrupt. New operations at the worksOperations resumed quickly again after the bankruptcy, and in 1927 the company began regular operations once more. The company struggled up until the mid-1930s, when the likelihood of a new world war created great demand for iron. A boom period and strong German capital in the company created good conditions for A/S Sydvaranger. The company was controlled by the Germans during World War II, and the Kirkenes works were bombed to destruction by the Allies.

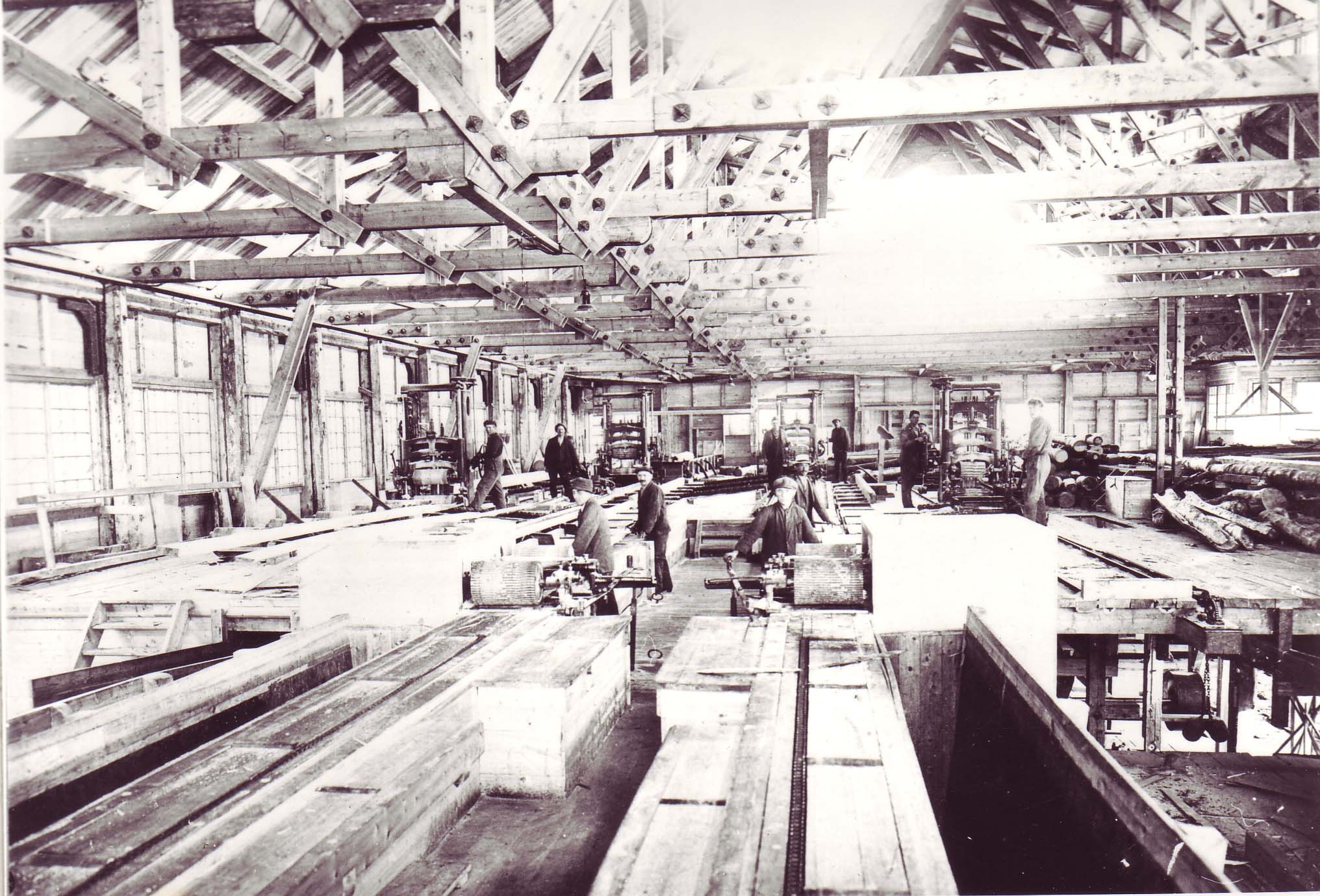

The need for energyDuring the building of A/S Sydvaranger’s works, electricity made its breakthrough and it was clear that the works would need a lot of electricity. There were plans to develop the Pasvik river to supply hydropower right from the start, but this was difficult because of the border conditions. A/S Sydvaranger therefore built its own steam electricity plant, Dampsentralen, which was finished in 1910. In the beginning Dampsentralen managed to supply both the works and the houses owned by A/S Sydvaranger, but it became clear early on that the electricity supply would be insufficient. The company decided to develop one of the watercourses in the area. Watercourse developmentIn 1919, A/S Sydvaranger began work on developing the Tårn river system to supply the energy for its works. The regulation of the river comprised three lakes and the intake to the Tårnet Kraftverk power station was sited at Rundvatn lake. The power station was in operation right until 1979, when the dam at Storvannet lake burst and the water masses did a great deal of damage to the surrounding countryside. The power station was never rebuilt. At the end of the 1920s, Kobbholm power station was built in Kobbholmfjord between Jarfjord and Border-Jakobselv.

|

Electricity to the peopleThe people who lived in A/S Sydvaranger’s houses got electric light early in the 1900s, while the rest of the population lived without any mains connection to electricity. The municipal council was obliged to buy power from A/S Sydvaranger and the power line network was developed. Initially, the network covered only the Kirkenes-Bjørnevatn area. The people living closest to Tårnet power station also benefited from the electricity. The Sandnes area was connected to the network in 1934 and two years later the power line was extended to cover Svanvik.

Harefossen KraftaksjeselskapThe power company Harefossen Kraftaksjeselskap was formed in 1939. The old plans to develop the Pasvik river were again relevant and, prior to the company being established, contact was made with both the Finnish and Norwegian authorities to negotiate an agreement to develop the waterfall at Harefoss. The project was put on ice when war broke out in 1940. The power station in Jäniskoski is builtFrom 1920 and until after World War II, the east side of the Pasvik river was Finnish and they also had a need for electricity. The mining company Petsamon Nikkeli Oy needed energy, so the power station in Jäniskoski was built. The construction period was from 1938 to 1942. With that, the first power station in the Pasvik river system was a reality. A dam was also built at Niskakoski to increase the station’s utilisation of energy. The Pasvik river has its source in the Inari lake, which then as now lies in Finland, and it was clear that there would have to be rules and regulations to regulate the lake. These regulations were drawn up in 1943.

Kirkenes, 4 June 1899. This was before the mining company A/S Sydvaranger was established. In the following decades the town developed at an enormous rate. The population were mostly Sami, Finns, Russians and a few Norwegians, including Dr. Wessel and his wife. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

During the building of the works in Kirkenes. A/S Sydvaranger’s operations formed the basis for the development and expansion of Kirkenes. The company occupied large parts of the headland and the rest of the town’s buildings were built around the company’s buildings. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

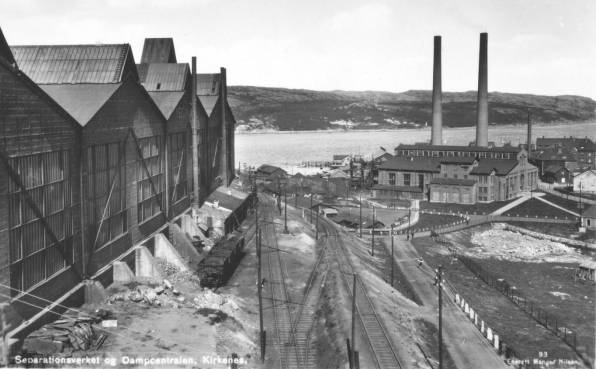

The plant built by the steam electric company Aktieselskabet Sydvarangers Dampsentral was finished in 1910. Until the development of the Tårn river system in 1920, the company supplied electricity to A/S Sydvaranger’s mines and works and employees’ homes. The electricity plant was bombed and left in ruins by the Allies during World War II. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Construction workers at the mines in Bjørnevatn. It was heavy work and in the early days the workforce fluctuated a great deal, owing to the difficult climatic conditions. By the end of 1907, there were 450 employees. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

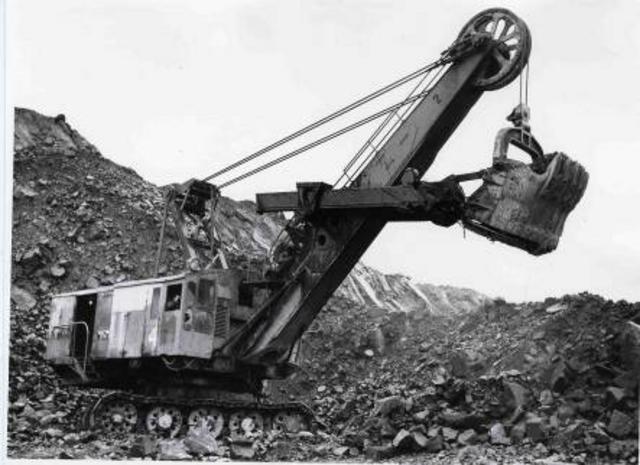

In order to obtain the iron ore from the mines in Bjørnevatn, a lot of gangue (the worthless rock in which the ore was found) had first to be blasted out. Huge machines had to be used for this work. The employees received all their training from A/S Sydvaranger and in many areas the company did pioneering work. A/S Sydvaranger became not only a workplace for the employees but also an educational institution. The company also provided other benefits: the employees had electric lighting in their homes long before the rest of the municipality, they were given cheap loans to build houses, and they received magnificent Christmas gifts that provoked envy among those of the local community who did not work in the mines. In addition, the company organised a number of welfare initiatives that benefited the entire community, building an indoor swimming pool, a cultural centre and a cinema. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

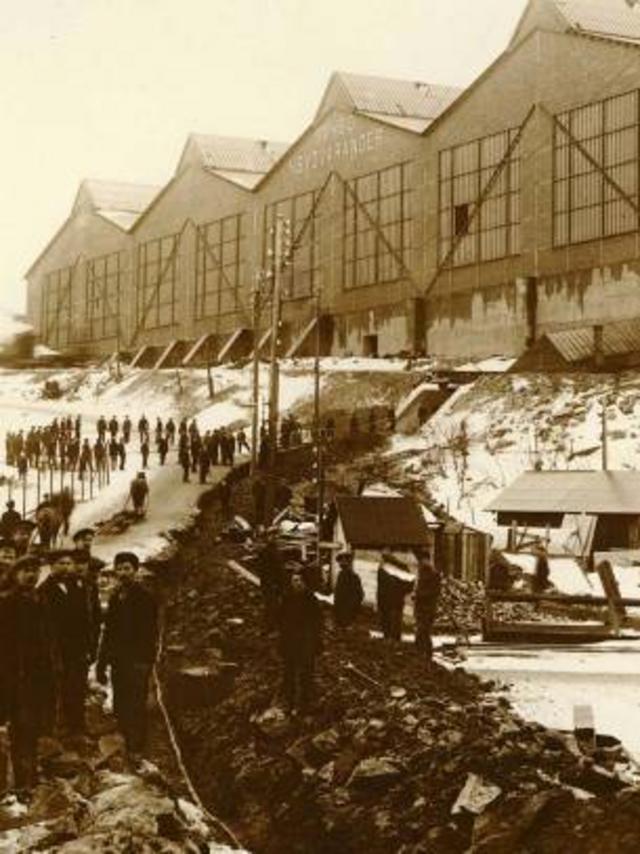

The famous façade of the briquette works in Kirkenes. The employees worked shifts at the works, enabling them to operate continuously, and this photograph was taken at the end of a shift. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

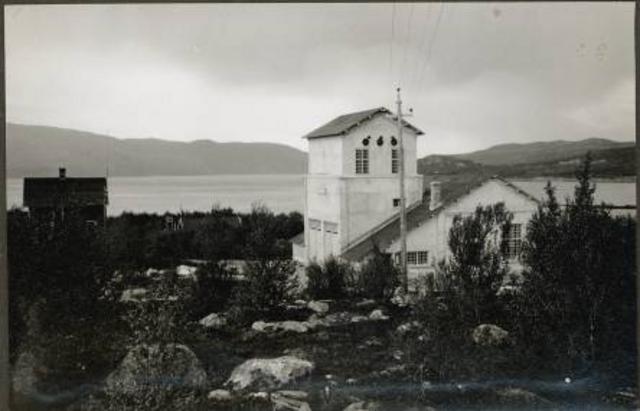

Tårnet power station when it was finished in 1920. This was A/S Sydvaranger’s first watercourse development project. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The old steam electricity plant today. The once so enormous building is dwarfed next to the Kimek hall. Kimek now owns the old plant and has turned part of it into open-plan offices. Kimek is a shipyard and many of its customers are Russian trawlers. (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

A nine-kilometre railway was built to transport the ore from Bjørnevatn to Kirkenes. This is the most northerly railway in the world, and here we see the DE-100 locomotive pulling the wagons filled with ore. (Photo: Ørjan Jerijervi) |

|

Collaboration on the joint development and utilisation of hydropower in the Pasvik river system is an old idea. Owing to difficult border conditions, nothing was done about these plans until after World War II. The unusual thing was that this collaboration began in the middle of the Cold War, when co-operation between East and West would otherwise have been considered impossible. There was an increased need for energy on both sides of the border, both for homes and industry. The hydropower development began in the 1950s. Seven power plants were built in the river system over a number of decades. Cold WarAfter World War II, the world entered the period known as the Cold War. East stood against West and co-operation between the two poles of power was not possible. After World War II, Petsamo came under Soviet rule and it became impossible to cross the Pasvik river. What had hitherto been a connecting link between neighbours now became a barrier. Major political power games have consequences right down at local level, and Sør-Varanger found itself in the middle between the two superpowers of the Soviet Union and the USA. It seemed that the old plans for a joint development of the Pasvik river would have to be buried for good.

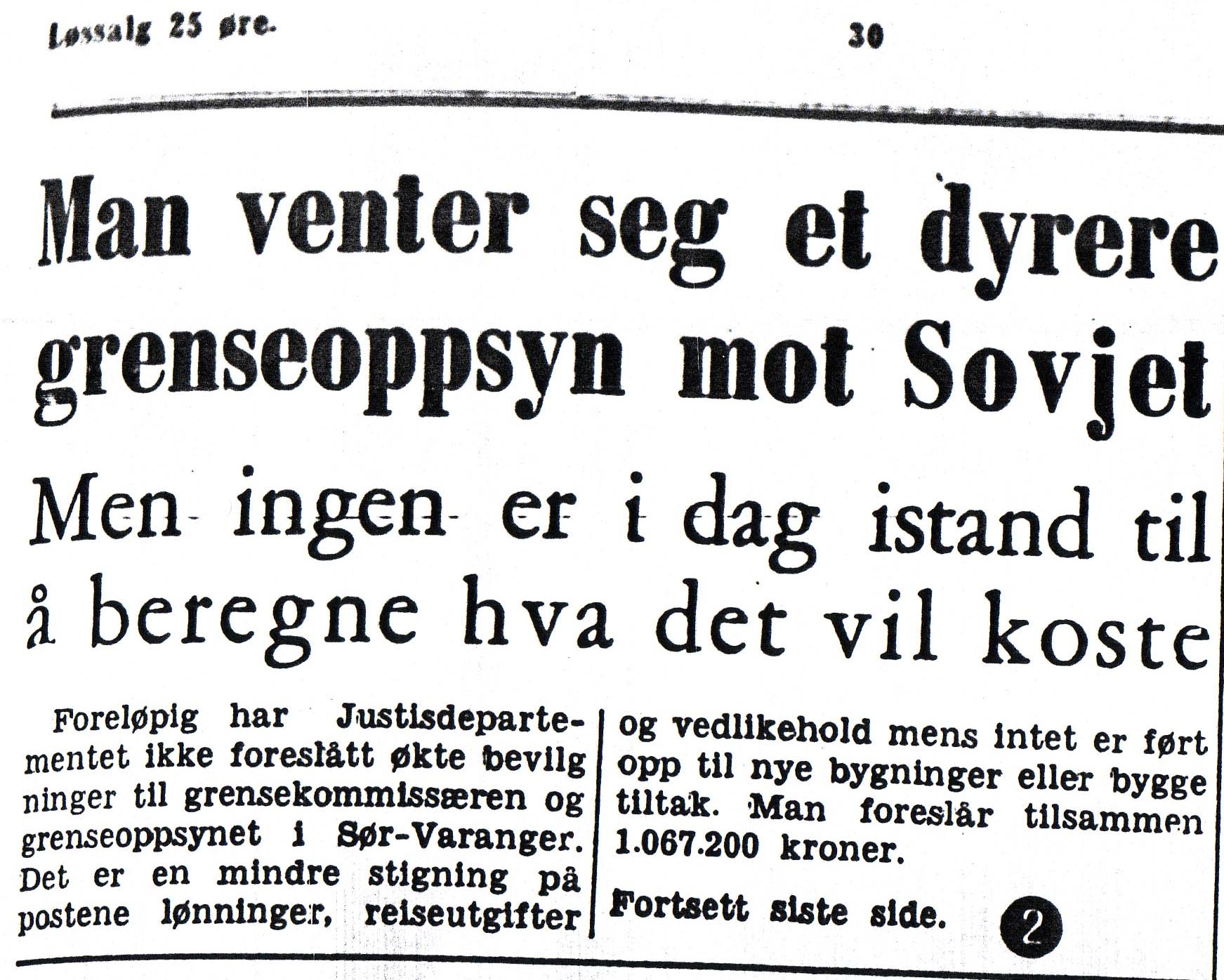

Development plans unearthed againAfter the war, both Norway and the Soviet Union wanted an agreement to utilise the hydropower from the Pasvik river system for mutual benefit and fair apportionment between the two countries. Already in 1945, the Soviet Union had intended to develop the falls at Skoltefoss by Boris Gleb, although nothing came of that for a while. In 1955, while on an official visit to Moscow, the Norwegian Prime Minister, Einar Gerhardsen, raised these plans with the Soviet authorities. A Norwegian-Soviet committee of experts drafted an agreement to apportion the hydropower from the Pasvik river, which was signed in 1957. Reconstruction and increased need for energyThe Allies’ bombing of Kirkenes at the end of World War II was a catastrophe for the little town, virtually all the buildings were destroyed and the population had to embark on the heavy task of reconstruction. Dampsentralen, the steam electricity plant, was in ruins after the bombing, which meant that people only had access to a minimal electricity supply. Concurrently with the reconstruction of Kirkenes, it was also decided that A/S Sydvaranger’s works would be rebuilt. In 1952, the works were ready to start new iron ore production. The need for power among both the local population and industry was growing at a great rate, and the idea was raised of linking all the municipalities in the eastern part of Finnmark to form a single electricity supply area. Varanger Kraftlag A/L is formedThe power company Varanger Kraftlag A/L was formed in 1948. The idea was that big, economically powerful forces would be responsible for the hydropower development that was to come. In 1953, Varanger Kraftlag began supplying electricity to Sør-Varanger. This was not well received by the local people, however. They had had electric light for many decades through A/S Sydvaranger’s steam electricity plant and the new venture created no improvement in the electricity supply. The company struggled to deliver a regular electricity supply and had to resort to power rationing, which the people were unused to. Some thought they had been cheated and that the electricity supply had deteriorated with Varanger Kraftlag. The employees of A/S Sydvaranger got their electricity from the company right up until 1965, when Varanger Kraftlag also took over supplying these households. Apportionment of the riverAs early as 1947, Finland and the Soviet Union signed an agreement to regulate the Inari lake. Finland had already built the power station in Jäniskoski and subsequently in Kaitakoski. Through the agreement signed with Norway in 1959, the Soviet Union gained the right to build a power plant at Boris Gleb as well as another two power stations in the upper section of the Pasvik river. In return, Norway was allowed to build a power plant in the middle section of the river. The development would be accomplished by developing two waterfalls, Skogfoss and Melkefoss. The 1959 AgreementIn 1959, an agreement was signed between the then Soviet Union, Finland and Norway to regulate the Inari lake. In the midst of the Cold War, when the world was dominated by suspicion, the nuclear arms race and cool balance-of-power relations, these three countries managed to draft and arrive at a joint agreement for the hydropower development of the Pasvik river, the border river between East and West. The agreement has remained in force ever since. |

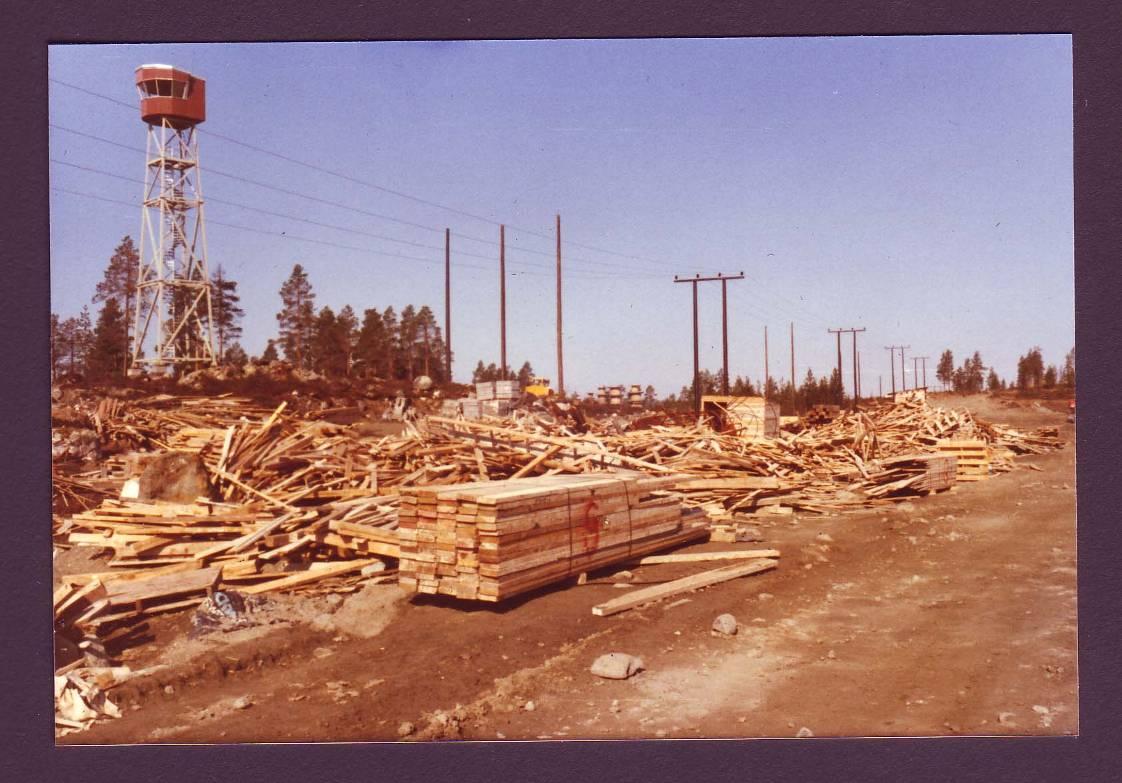

The hydropower development startsLarge parts of the Jäniskoski power station were destroyed during the German retreat in World War II, and after the agreement between the Soviet Union and Finland to transfer the plant to the Soviet Union in 1947 a project was begun to rebuild the power station. The dam in the Niskakoski falls and the power station in the Jäniskoski falls were finished in 1950. In 1955, the first turbine in the Rajakoski falls was started up and the Soviet Union’s power station came into operation in 1956. Hevoskoski (Hestefoss) was finished in 1970. Skogfoss was the first Norwegian waterfall to be developed and the power station there became operational in 1964. The power station at Melkefoss was not finished until 1978 when Norway had completed its part of the hydropower agreement. Over a period of 30 years, all the waterfalls in the Pasvik river were developed for hydropower. Two Finnish, three Russian and two Norwegian power stations were required to supply the population and industry with electricity. Today, new sources of energy are being sought to meet the needs of all parties.

The west side of the Pasvik river. On the other side can be seen Boris Gleb and the power station there. (Photo: Ingar G. Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Article from the local newspaper, Sør-Varanger Avis, reporting old plans for the development of the Pasvik river.

After the bombing of Kirkenes, only ruins remained and the town had to be rebuilt from the ground up. Many who were not forcefully evacuated during the German retreat spent the first winter in the old foundations and cellars, covered by temporary roofings. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The Mennika dam at Skogfoss. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

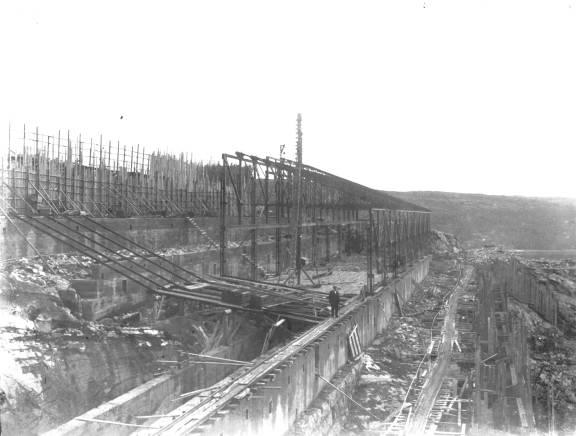

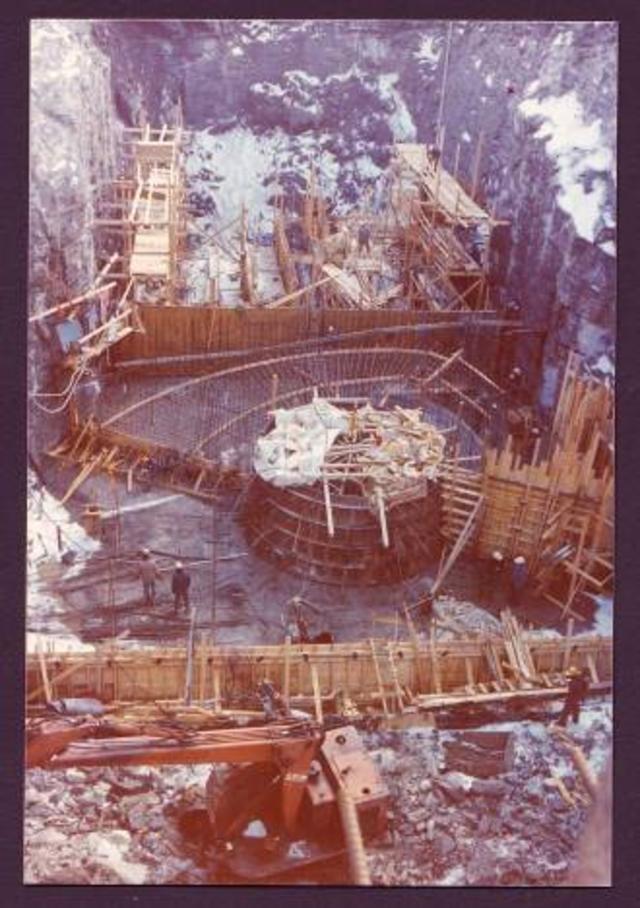

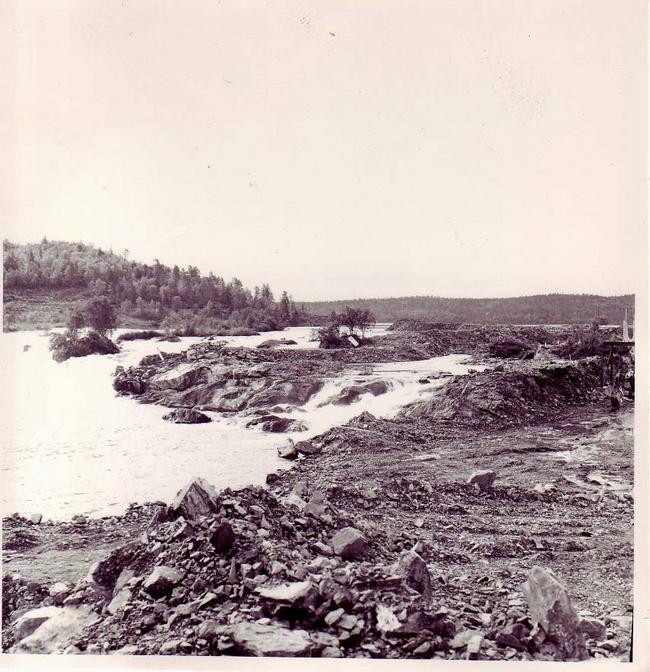

During the building of the power station at Melkefoss. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

The power station at Skogfoss with the inlet channel and the dam. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

The Pasvik river in Norwegian; Paatsjoki in Finnish; Patso-joki in Russian. (Map: NVE)

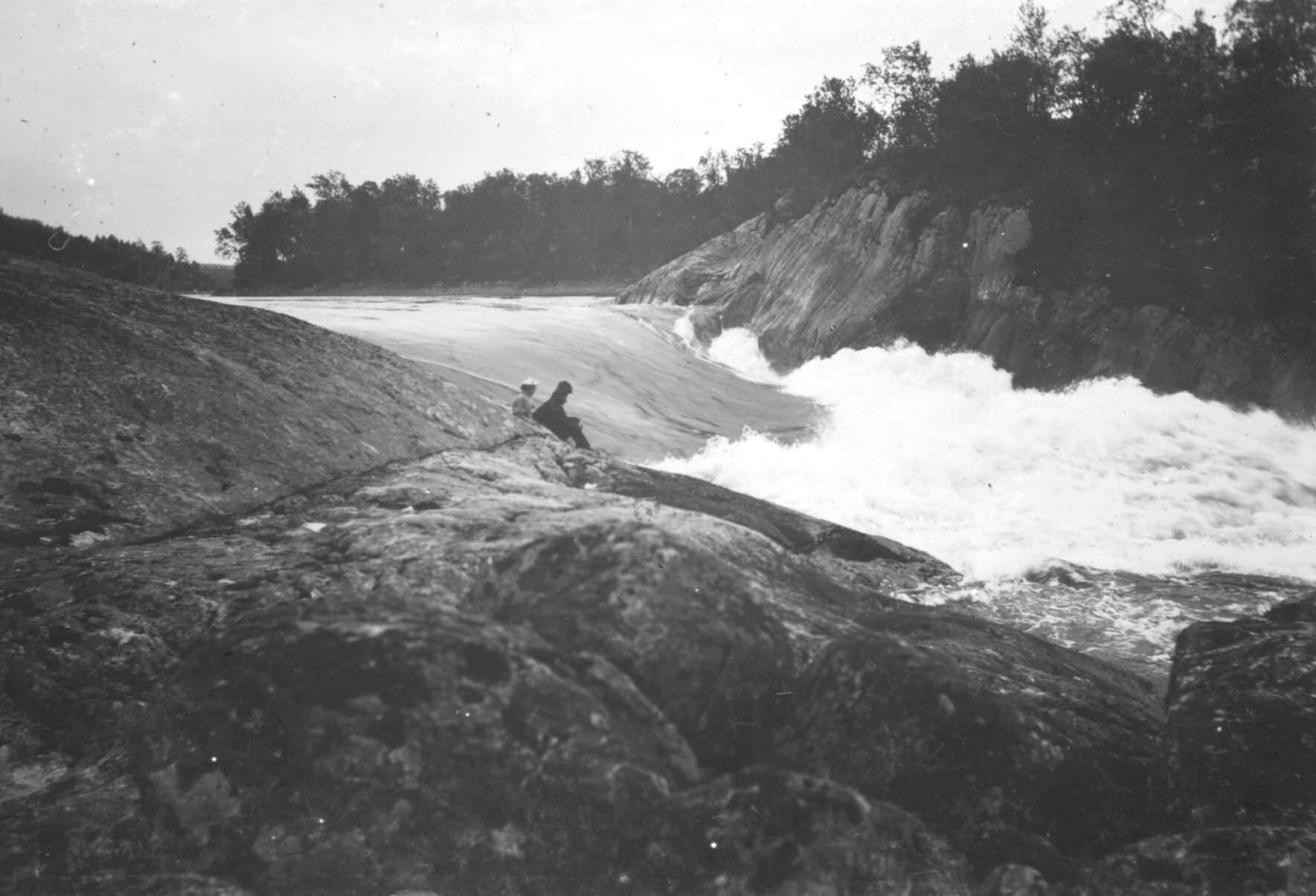

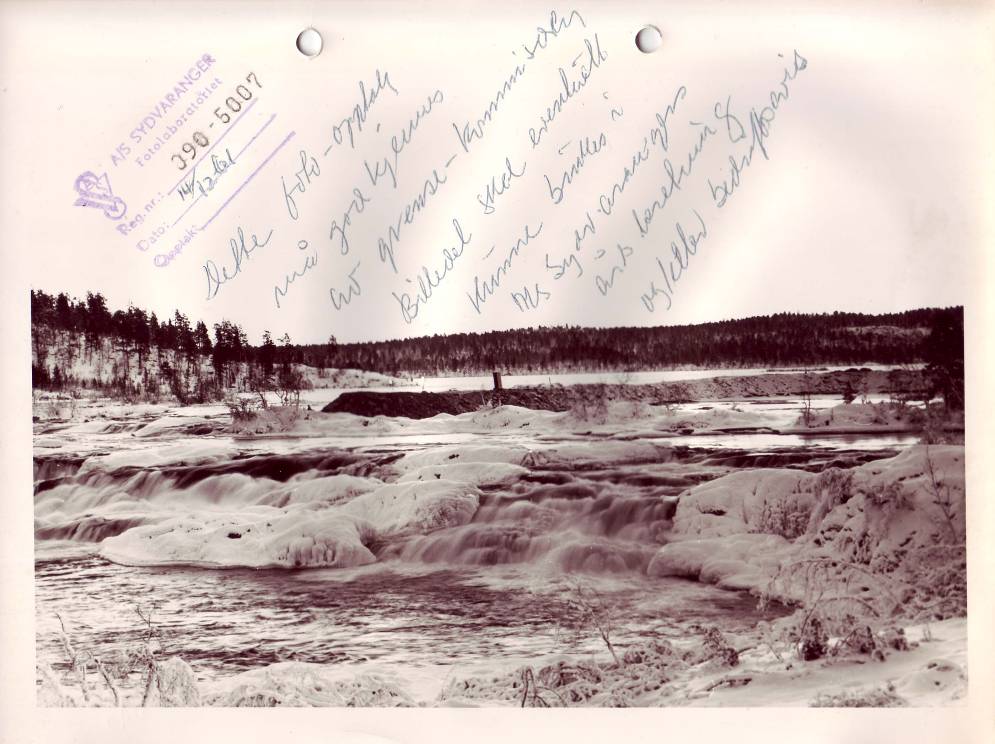

Rajakoski, Grensefoss before the development (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The border between the Soviet Union and Norway was closed in 1945. As the border between East and West, it was heavily guarded on both sides. It is strictly forbidden to cross the border and stiff fines await anyone who fails to comply. Although the border is guarded 24 hours a day, it is possible to go right up to it, where the border posts stand with only a few metres in between. Every year there are tourists who cannot resist the temptation to venture just a little way into Russia. They quickly realise that doing so has made them poorer to the tune of NOK 5,000! (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum) |

|

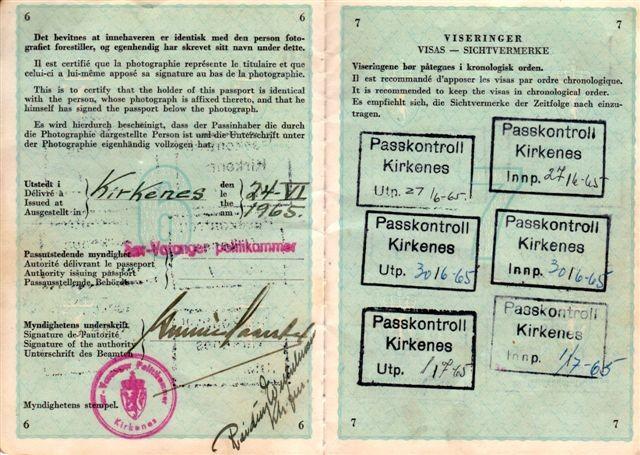

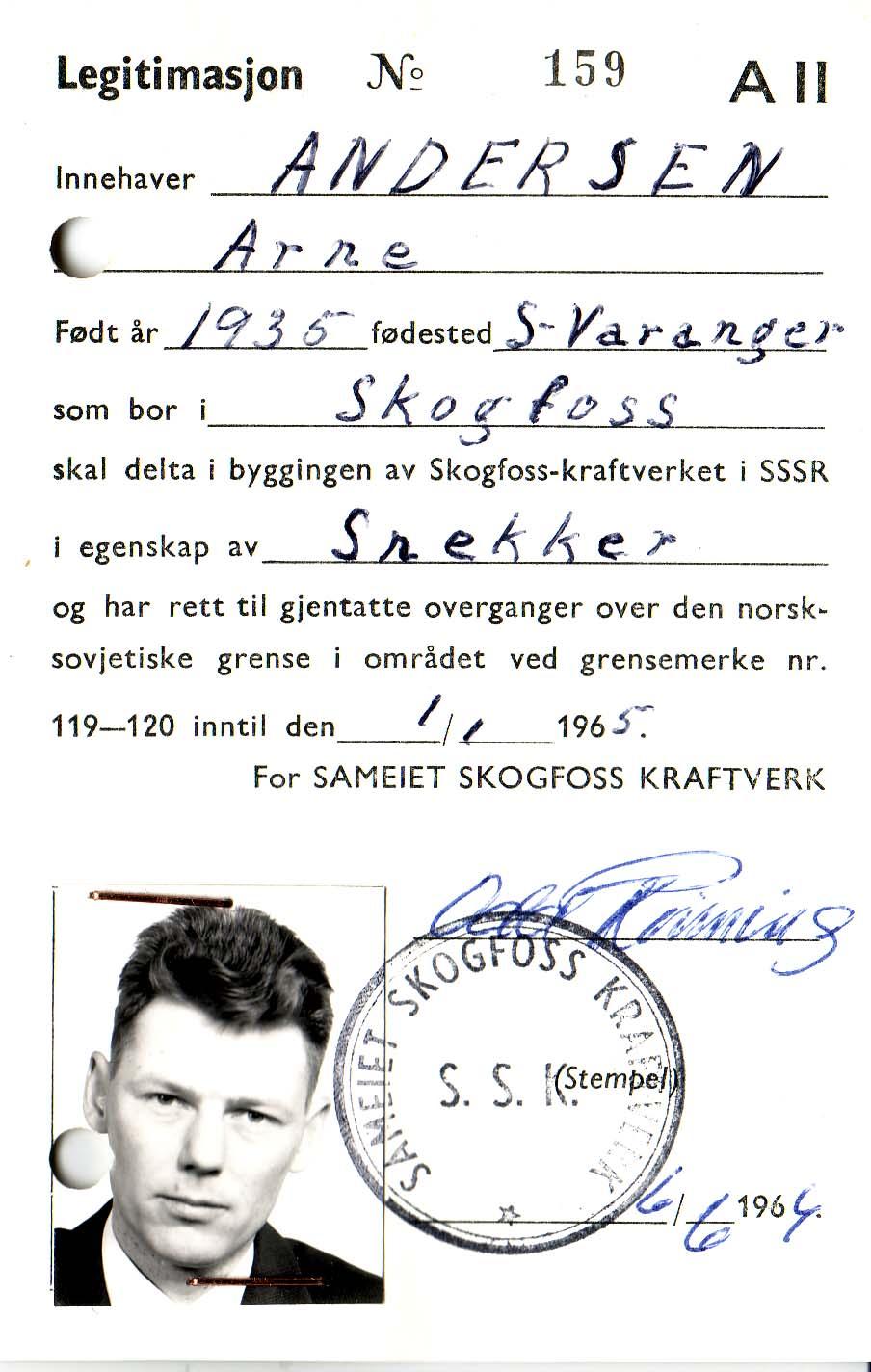

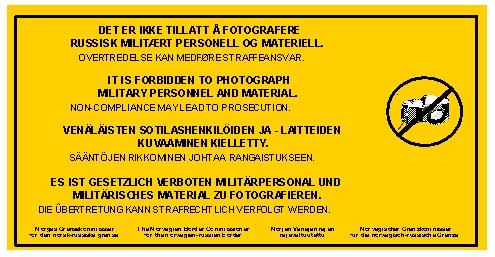

The development at Boris Gleb would be unusual in the context of the hydropower co-operation between Norway and the Soviet Union. The power station was built by Norwegian contractors, who also built a small town around the construction site. For a short period in connection with the construction works, Boris Gleb was opened to the public without any need for a visa. The arrangement did not last long as there was a great fear during the Cold War of agents being recruited and of contact between agents. AgreementsSince the development of the Pasvik river would impact on the areas of both parties, and in some instances would stretch far into the other’s territory, Norway and the Soviet Union agreed that both could use this land free of charge to the extent necessary for the operation and maintenance of the future hydropower installations. Parts of the Soviet Union’s installation at the power station in Boris Gleb would be in the Norwegian area. In 1955, the Soviet authorities announced that they were willing to make over to Norway 40% of the power generated by this plant. Norwegian firm gets the jobThe building of the power station at Boris Gleb started in 1960 with Norwegian contractors, but using a Soviet generator and turbine. The Norwegian firm Norelektro was responsible for the technical side of building the actual power station. The building contractors Selmer, Furuholmen and Astrup Aubert were also involved in the development. Local builders, such as Byggmester Ragnar Ulvang, Brød. Zakariassen and others, built houses, a shop, a school and the community centre in Boris Gleb. SurveillanceThe Norwegian workers were under close surveillance from both sides during the construction period. Passes were issued to make access easier from the Norwegian side and into the Soviet Union. The pass was a 24-hour pass and within that time the worker was required to leave the Soviet area. The actual working process was also under surveillance; there would be no opportunity for contact between Norwegians and Russians. KGB officers kept a continuous watch on the workers. Photography forbiddenThere have always been varying degrees of restrictions on photography along the border. During the Cold War, it was totally forbidden to take photographs over the border and for a while it was not permitted to take a camera up to 1 km from the border. During the hydropower development it was difficult to enforce the photography ban and the issue was discussed by the Border Commissioners. On one occasion a Soviet worker was taking photographs of his colleagues and unfortunately got a bit of Norway in the background. The photograph was also published in a magazine, and as a result of this episode it was discussed whether the ban could be relaxed a little. Boris Gleb, the meeting placeBefore the border was established in 1826, Boris Gleb was a meeting place for people. The Greek-Orthodox Chapel lay on the west bank of the river and to it came East Sami from the entire area to attend services, weddings and baptisms. During the period of the hydropower development, the Soviet Union gave the public the opportunity to visit a small area in Boris Gleb without having to have a visa. This area contained a bar, a hotel and a shop selling cheap spirits and cigarettes. There was no state wine and liquor store in Sør-Varanger in those days and so Boris Gleb was a very popular place to visit. Because of its location, it was easy to get to and there were no restrictions on the number of times one could enter and leave the Soviet Union over a 24-hour period. A smugglers’ trail was even created over Skafferhullet to Bjørnevatn. The arrangement was to last a year and the Soviet Union wanted to extend it, but Norway said no. The border crossing made it easy for agents in the service of the Soviet Union to come into contact with their principals, and during the Cold War this was something that had to be prevented at all costs. For 59 days, the Norwegian population went back and forth in a kind of shuttle traffic taking full advantage of the chance to buy cheap goods. Russian electricityAn agreement was signed between Norway and the Soviet Union to import electricity from the Boris Gleb power station, and a power line was built to Kirkenes. The line co-ordinating the supply with the Soviet Union’s power grid was finished in 1971. This power outtake from the Soviet grid was important for Norwegian preparedness in the area, particularly until Finnmark became connected up to the co-ordinating grid in North Norway in 1974. However, the electricity from Boris Gleb created problems for the population since Norway has higher requirements with respect to frequency and time variations in the electricity supply. People had difficulties with electrical appliances when the Russian electricity came in. In 1986 the switching station in Boris Gleb was rebuilt with Norwegian help and the problems were over. Salmon fisheryThe Pasvik river was rich in salmon, and even had its own species of salmon. Many people fished for salmon when it swam up-river to spawn. At Elvenes and up towards Boris Gleb there were many small salmon-fishing huts that were used in the salmon season. When the development of the Pasvik river began, people were aware that the salmon might disappear. In Boris Gleb an attempt was made to build a salmon ladder, but it was unsuccessful. Today, there are no salmon in the Pasvik river and the resource base for salmon fishing has gone. The salmon fishing huts can still be seen along the riverside, but they have been abandoned and are exposed to wind and weather. |

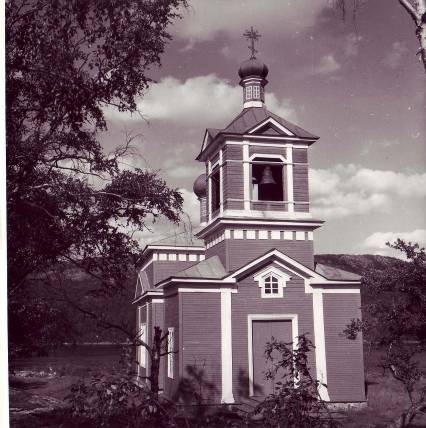

The chapel in Boris Gleb created problems when the border was to be drawn in 1826, as it stands on the west bank of the Pasvik river and the river could not be used as the border. Since the ground on which the chapel stands is holy, it could not be moved to the other side. The solution was that Russia got the territory around the chapel and was obliged to surrender Grense-Jakobselv. (Photo: Wilse. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The falls at Skoltefoss before they disappeared with the development in Boris Gleb. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The hotel in Boris Gleb, 1939. (Photo: Unknown)

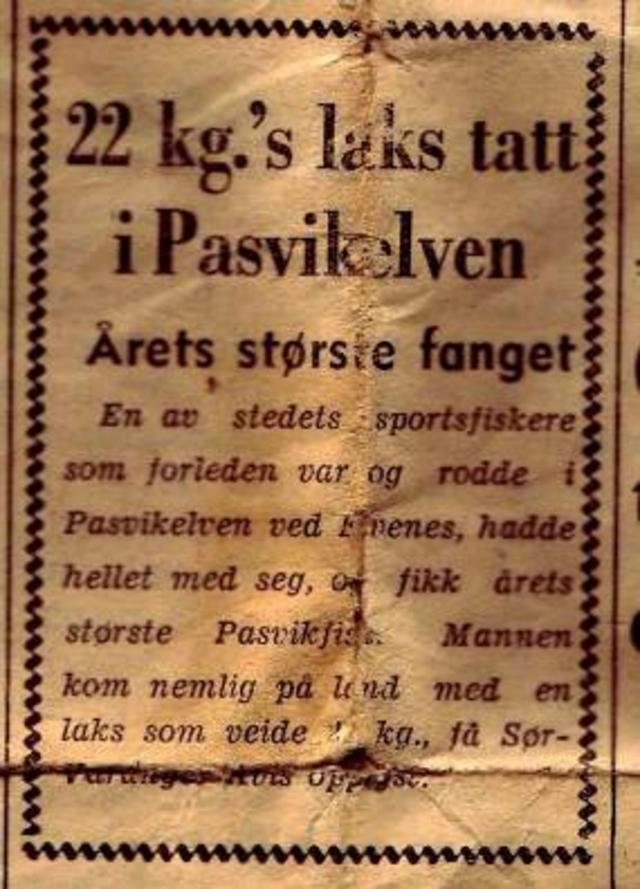

Salmon in the Pasvik river were renowned for their large size. Here is a report of a salmon weighing 22 kg. (Source: Sør-Varanger Avis, 25 July 1959)

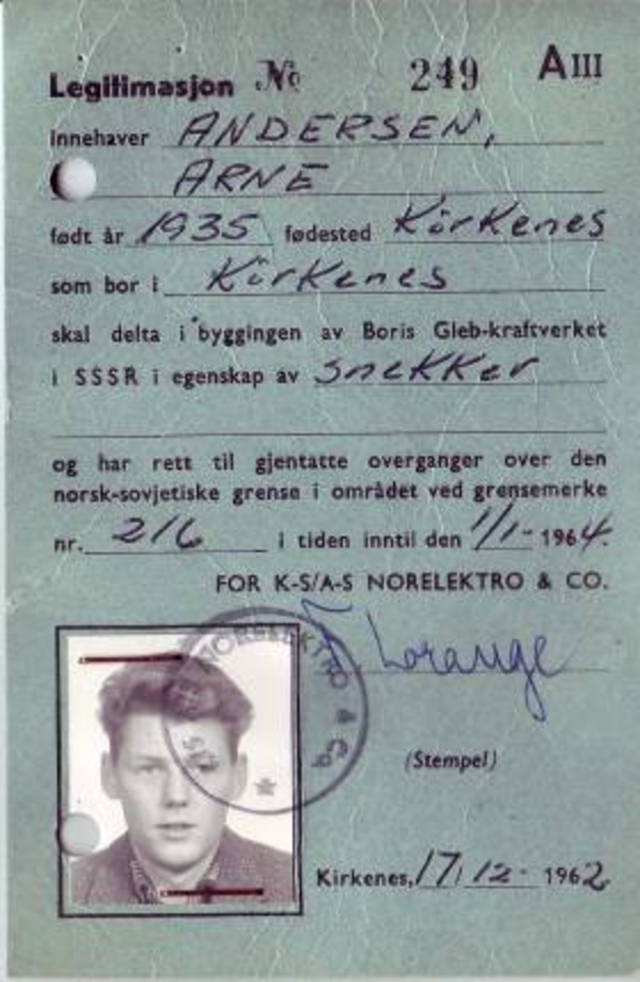

Pass used at the Boris Gleb power station. This was a so-called 24-hour pass and the holder had to leave the Soviet Union within that time. (Source: Arne Andersen, Skogfoss)

Old huts where salmon fishers lived during the season. They have been unused since the salmon population disappeared. (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

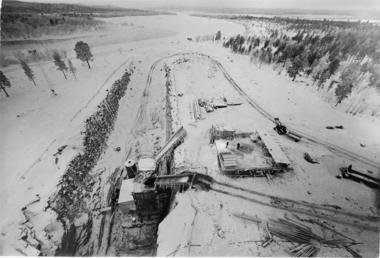

The dam at Boris Gleb seen from above. (Photo: Tor Sandø)

Trifon’s Cave just below Boris Gleb. It is said that the holy monk Trifon hid in this cave to escape from robbers, thus saving his life. East Sami who passed the cave would throw in coins to bring them luck when fishing. Today, an icon of the Holy Virgin has been set up there. (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Soviet and Norwegian officers in Boris Gleb. (Photo: Edvardsen Brothers, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections) |

|

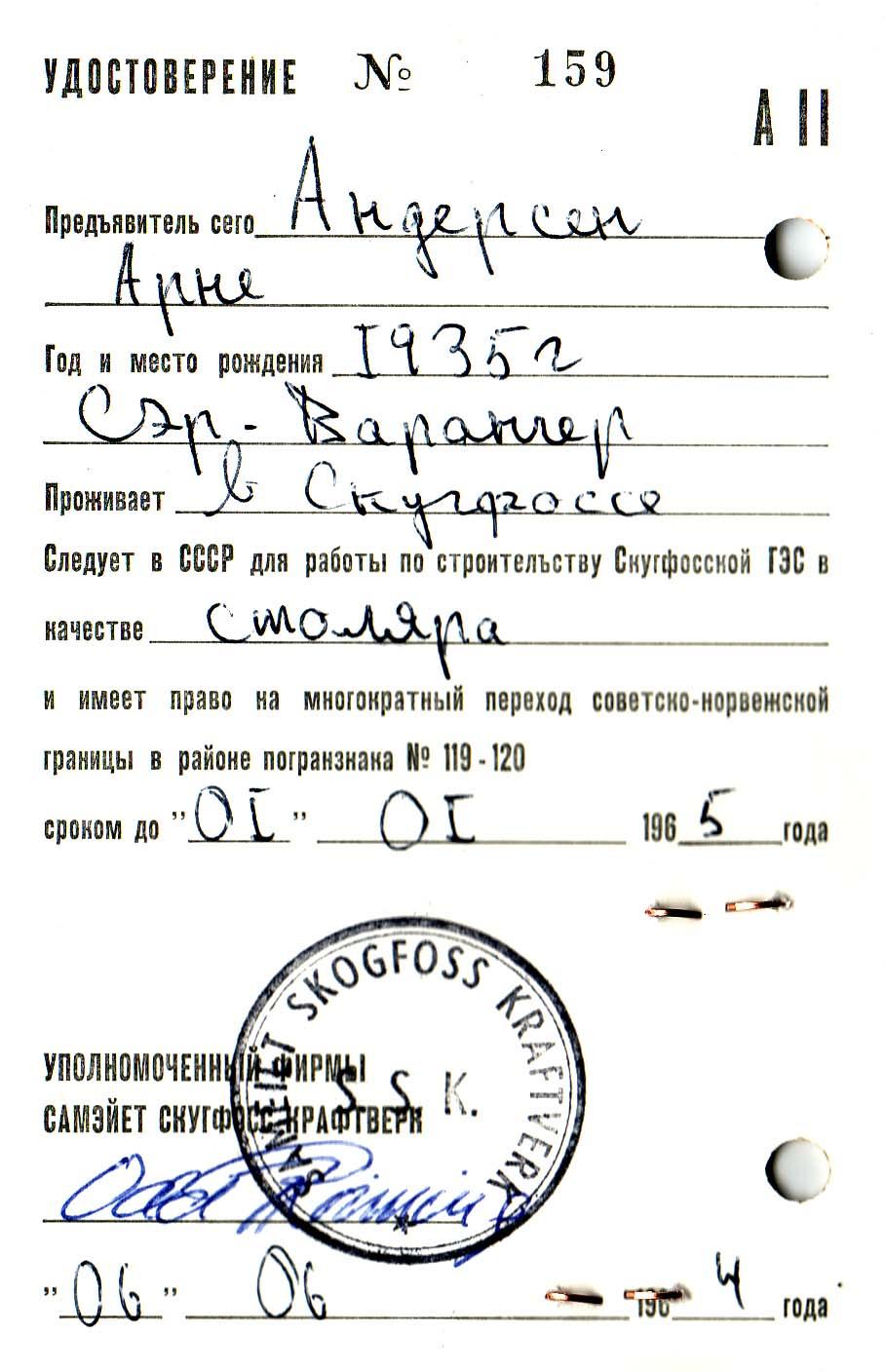

In connection with the hydropower development, special passes were made for the Norwegian workers working on the Soviet side, which had to be shown when entering and leaving the Soviet Union. There were also KGB officers who shadowed the workers to prevent Norwegians and Soviets from having unnecessary contact. Norwegian firm working on Soviet soilA Norwegian firm from southern Norway was responsible for the construction work at the hydropower development project on the Soviet side. Local firms were contracted to build homes, shops and schools for the Soviet Union. At the Skogfoss development, the main dam was a long way into Soviet territory and the Norwegian workers had to travel several kilometres to get there. This posed problems as there were no roads or bridges. Consequently, the work of road- and bridge-building was the first that had to be done. Bulldozers and other big machines were hauled across the frozen river on runners in winter and floated across on rafts in summer. Contact between Ola and IgorAt the Skogfoss development, there was not much contact between the Norwegian and Soviet workers. Both sides encouraged the workers to have as little contact with one another as possible. However, at Melkefoss there was a little more contact, and here the Norwegian workers were able to have contact with the Soviet staff who lived on-site at the plant. This led to a bit of bartering between them; the Norwegians got vodka in exchange for clothes, fishing nets and other goods that were in short supply in the Soviet Union. There was more contact between people at Boris Gleb as the public were able to enter without a visa. Here, several attempts were made to recruit agents in the local bar, and relations were carefully monitored by both sides. SurveillanceDuring the construction process it was important for both the Norwegian and Soviet authorities to be in control of the workers. From the Norwegian side, everyone was encouraged to have no contact with the Soviet workers. At the same time, there were KGB officers trailing the Norwegian contractors. One of the Norwegian bosses had a KGB man with him everywhere, who spoke fluent Swedish. Having been in one another’s company for several weeks, they could not avoid getting to know each other slightly. Once, when the Norwegian had to go to the dam, he met the KGB officer quite by chance and was unable to greet him as it might be perceived as unnecessary contact. Who got the work?Before the Norwegian workers could work in the Soviet Union, they had to have security clearance from the Norwegian authorities. Not everyone was permitted to go onto the Soviet side to work. Individuals with Communist sympathies were unable to get security clearance as it was felt there was a potential risk for espionage and recruitment as agents. It has since emerged that attempts were indeed made to recruit agents. PassesSpecial passes were issued in connection with the construction work on the power plants. There were white passes for the Skogfoss plant and blue for Boris Gleb. The workers who worked on the Mennika dam, several kilometres inside Soviet territory, had yellow passes. |

|

|

The co-operation on hydropower development between Norway and the Soviet Union took place at a time when East and West regarded one another with suspicion. Intelligence gathering and espionage were a part of the Cold War. However, relations between the Norwegian and Soviet authorities, and Norwegian workers and Soviet soldiers during the development of the Pasvik river, were characterised as good. Ola and Igor managed this well. Hydropower development in the border countryIn Norway, before a river can be developed for hydropower, licences are required from a number of different authorities. This was also the case with the Pasvik river development. Here, though, it was also necessary to communicate with both the Norwegian and Soviet Border Commissioners. In addition, the border guard at the Sør-Varanger Garrison (GSV) were involved, as well as the Police Headquarters and the Police Surveillance Service in Kirkenes. Strengthened border guardGSV strengthened its guarding forces along the border and the police were also well represented. The large numbers of people and traffic in the border area led to a strengthening of the border inspection work, but it was doubtless also because of the Cold War between East and West. In the hydropower development budget, NOK 5 million were allocated to border and police inspection. Watch towersThere was a great deal of traffic in the border area while the four power stations were being built along the Norwegian-Soviet border. Many Norwegian workers crossed the river to work on the Soviet side. The Norwegian authorities wanted the traffic and activity by the border river to be thoroughly supervised. The power company developing the river, Sameiet Skogfoss Kraftverk, was obliged among other things to meet the costs of providing premises for the police and Armed Forces. An extra watch tower was set up. It was later discussed whether to sell the tower to the Armed Forces; they got the tower in the end, but had to pay for the move themselves. Permit to carry cameras«Photographing a neighbouring State’s territory and possession or use of a camera without a special permit while in the border area at a distance of up to 1,000 metres from the border is forbidden». This rule remained in force until the mid-1960s. Permission to carry a camera or to take photographs had to be obtained from the Norwegian Border Commissioner. The Border Commissioners in Norway and the Soviet Union frequently discussed the photography ban and the rules were gradually relaxed. It was particularly difficult to enforce the ban during the construction period. Frequent contacts with the Soviet UnionThere were frequent meetings between the Norwegian and Soviet Border Commissioners during the construction period. The Russian power stations along the border were built mostly by Norwegian firms. Much of the work went on in the neighbouring Soviet Union. The building of the four power stations led to a great deal of activity along the Norwegian-Soviet border. Border Commission meetingsMajor Oskar Kurthi worked for over 30 years at the Sør-Varanger Garrison (GSV) and at the Border Commission. “The meetings between the Border Commissioners were always very formal. Matters were discussed and documents signed. But after all the formalities were over, the atmosphere became more relaxed. Food was served and, on those occasions when the meetings were held in the Soviet Union, vodka appeared on the table. They didn’t quite understand that we couldn’t drink in the Russian way! We were at work and had to go home to our families,” says Kurthi. At some meetings, Norway, Finland and the Soviet Union were all represented. “I speak a little Finnish and managed to use the language. That was not very well received by the Russians. But it was probably because they felt a bit out of it,” explains Kurthi. Intelligence and the Cold War“Everything we saw and observed and the impressions we gained were reported. Naturally, this applied on the Russian side as well. This was during the Cold War period and both sides were aware of the situation,” says Major Oskar Kurthi. “I’ve always been interested in politics, but there was not much politics discussed in our contact with the Russian border guards. I remember, though, once in the early 1980s when one of the Russian officers expressed dissatisfaction with the system that clearly didn’t function. ‘There must be changes,’ he said. A few years later, he was right. Gorbatchev came to power and the changes soon came,” says Kurthi. Popov and BarabanovOle Sotkajervi from Stenbakk in Pasvik was one of many who worked in the Soviet Union during the construction period. “I did a few jobs on the Russian side at Melkefoss, including rock-blasting. We had Lieutenant Popov with us all the time. He spoke a kind of Swedish. He was a nice fellow, him and Barabanov,” says Sotkajervi. “We had been told by the Norwegian border police that we had to be careful about what we said; for the Russians would try to fish for information. Of course we didn’t give them any. But they knew where I lived!” Reindeer shot on the Soviet side“Once, when I was on the Soviet side working, Major Barabanov told us they had shot a Norwegian reindeer in the Soviet Union,” recounts Ole Sotkajervi. “Barabanov wondered how they were going to put things right. The reindeer’s owner, Nils Sotkajærvi, worked on a crane on the Norwegian side. The Russians borrowed our walkie-talkies and asked Nils if it was OK if he got a case of vodka in compensation. We had a good laugh, but I doubt that Nils ever saw anything of that case of vodka!” |

"This photograph must be approved by the Border Commissioner. The picture may be used in A/S Sydvaranger’s annual report and/or company newspaper". Skogfoss with the Soviet Union in the background. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger’s archives)

“I remember we had a Norwegian border commissioner who was very interested in Russian history. He enjoyed discussing history with the Russian border commissioner, who didn’t really know that much about it. At their next meeting the Russian border commissioner had an assistant with him who knew about Russian history. He was obviously keen to match the Norwegian’s expertise,” says Kurthi, who was assistant to the Border Commissioner in the 1980s. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Russian and Norwegian border markers at Skafferhullet. Oskar Kurthi worked for the Border Commission and had a lot of contact with Soviet border soldiers. “Our job involved doing all sorts of things. We moved border markers together with the Russians, and went out to fetch reindeer that had strayed across the border. We were also present at the watercourse management meetings between Norway and the Soviet Union. The watercourse people had their meetings, and we had our slightly more informal meetings in that connection,” says Kurthi. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

The bridge at Hestefoss. The photograph is taken from the Soviet side. Many Norwegians worked on the Soviet side during the development. (Photo lent by Birger Erlandsen)

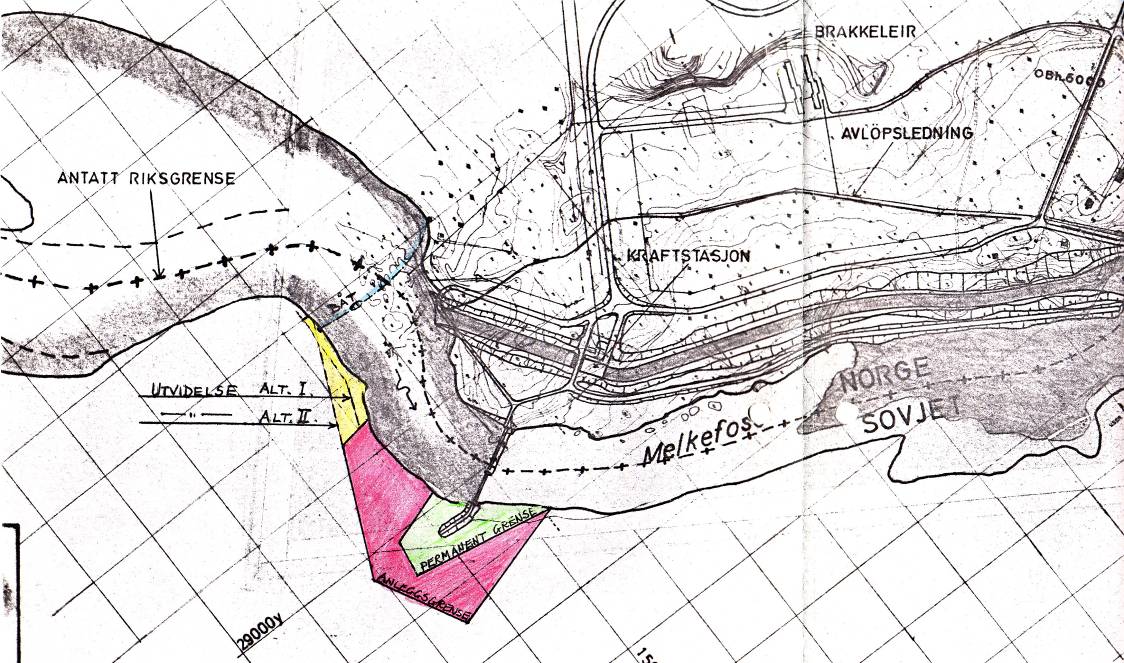

The Melkefoss area. Provisional and permanent borders have been drawn in. The blue line marks where the boat traffic to and from the Soviet Union would go. (Pasvik Kraft’s archives)

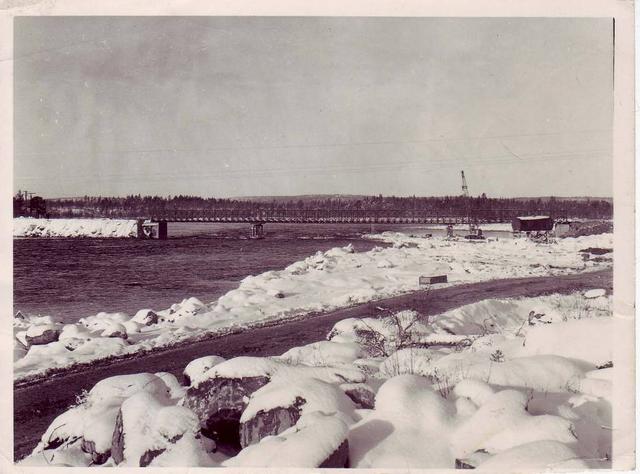

Transport to the Soviet Union during the construction period went on on the top side of the dam up towards the left. All traffic ceased on 25 November 1978. Melkefoss came into operation on 1 September the same year. All entry permits to the Soviet Union were withdrawn. Only the operational personnel were permitted to inspect the dam on the Soviet side. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

Norwegian border guards patrolling the Pasvik river. The border between Norway and Russia is well guarded by Norwegian and Russian border soldiers. (Photo: Ragnhild Nordahl Næss, Sør-Varanger Avis)

“Everyone kept an eye on what we did in the Soviet Union. The Russians were of course there all the time and watched us and would chat with us. The Norwegian border guards also saw most of what went on from their observation posts. But there was one time when Ørnulf Mathisen and I decided we would have a bit of fun with the Norwegian border guards,” explains Ole Sotkajervi. “We built a gapahuk [shelter made from branches] with the roof towards the Norwegian side. We made a fire, ate our packed lunch and boiled some coffee. They didn’t see us from Norway, and we heard nothing about it when we got back to Norway again.” (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen)

Border fence between Norway and Russia on the west side of the Pasvik river. The buildings in the background are the Russian village of Boris Gleb. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum) |

|

Norway and the Soviet Union agreed to develop the Pasvik river at the end of the 1950s, and the rapids and waterfalls were apportioned between them. The Soviet Union brought the power station at Boris Gleb into operation. The Pasvik valley’s mightiest waterfall, Skogfoss, stood next in line. Skogfoss was developed without any great discussion in the local community. The Pasvik AgreementThe Pasvik Agreement of 18 December 1957 apportioned the Pasvik river between Norway and the Soviet Union. In the document, each state also surrendered land to the other in the construction period, which could be used free of charge. Norwegian workers worked in a delimited area in the Soviet Union, and parts of the dam at Skogfoss still lie in present-day Russia. A dam was also built in the Mennika river, a tributary of the Pasvik. This dam lies several kilometres inside Russia. A/S SydvarangerIn 1958, A/S Sydvaranger was granted a licence to develop Skogfoss. Proposition to the Storting No. 124 (1960-61) was put before the Norwegian parliament. It was entitled «Lease of Skogfoss in the Pasvik river to A/S Sydvaranger for development by A/S Sydvaranger and Varanger Kraftlag A/L in partnership and financial participation from the State». It appears from the documents that the company would have difficulty in carrying out the Skogfoss development without the government’s help or participation. The company said this was because of:

A committee was appointed to look into alternative solutions. The power company Varanger Kraftlag entered the picture as a natural partner. Also the government saw the importance of the development. A/S Sydvaranger wished to supply its own staff, both workers and salaried employees – 3,500 people in total. Varanger KraftlagIt was pointed out in the Proposition to the Storting that the supply area covered by Varanger Kraftlag was approximately 2,000 km² larger than the combined areas of Oslo, Akerhus, Vestfold and Østfold. The area was enormous. It was a natural step on the government’s part to get involved in the project in order to secure electricity supplies to the area. Varanger Kraftlag had its application approved for assistance to partially cover its share of the construction costs of the power plant and transmission lines. These costs would be met through the national budgets for 1962-64 and, if necessary, 1965. A/S Sydvaranger and Varanger Kraftlag formed the company Sameiet Skogfoss Kraftverk. Ministry of IndustryThe Ministry of Industry took the view that the development must be carried out as soon as possible, for the following reasons:

The Ministry assessed the development of Skogfoss as important as regards a more secure supply of electricity to the area and for the sake of employment. Land areas under waterThe development of Skogfoss was broadly supported in Sør-Varanger and in the Pasvik valley. The prospect of cheaper and more secure delivery of electricity was positively received. The development also created many jobs. The damming of the Skogfoss falls led to several farms being submerged as well as agricultural land and leisure areas with holiday cabins. The farms by Langvannet were particularly affected, and many were laid under water. By the end of 1962, the builder, Sameiet Skogfoss Kraftverk, had paid almost NOK 3 million in compensation to those affected by the waters rising by almost nine metres. |

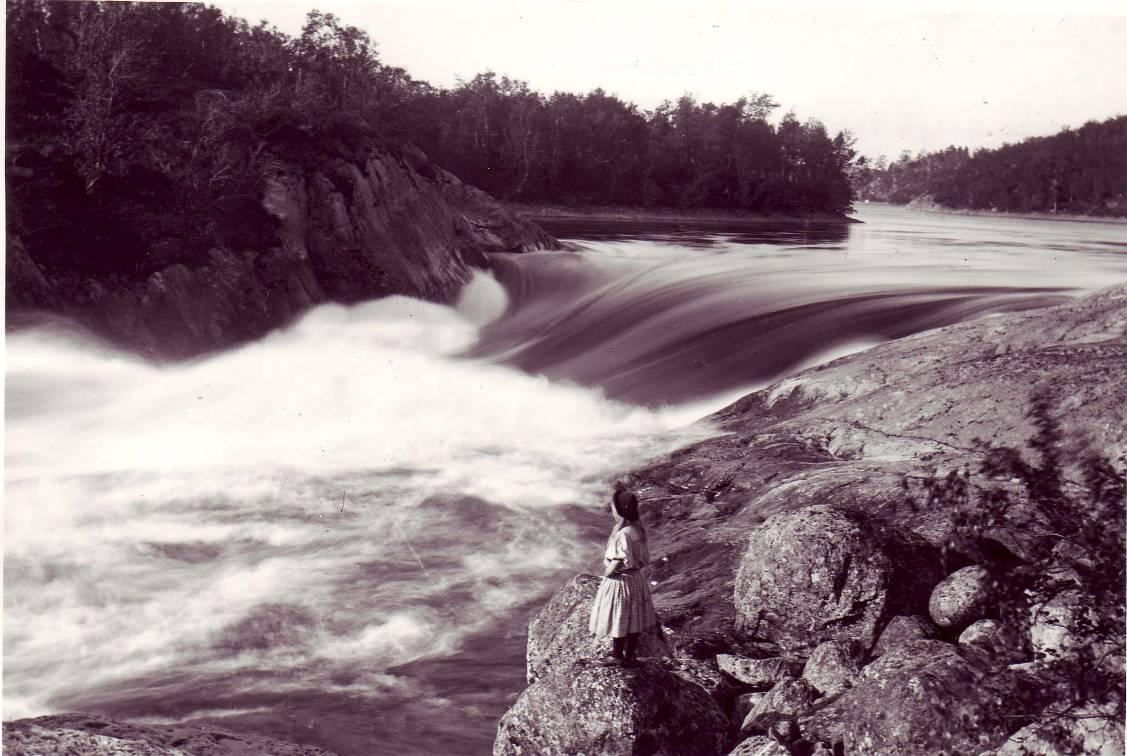

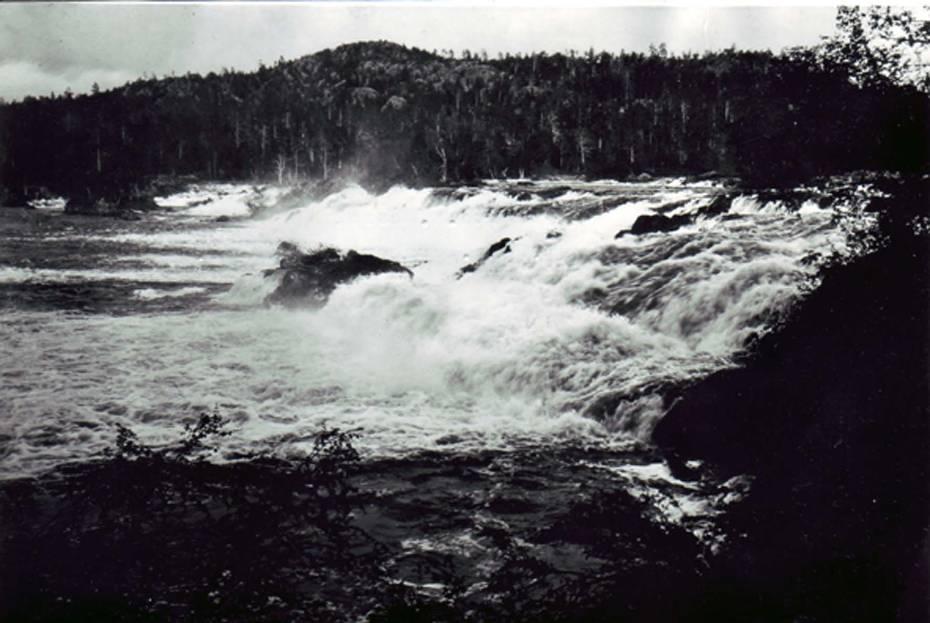

The last remnant of the old riverbed. The Pasvik valley’s most magnificent falls at Skogfoss, in the summer of 1962. There was little opposition to the hydropower development, probably because it delivered a more stable electricity supply to the people of the Pasvik valley. The power line to the valley was vulnerable to bad weather, and an extra line meant that power cuts did not last as long. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger’s archives)

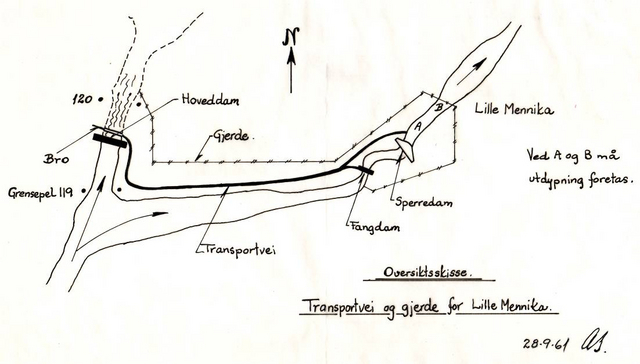

Overview sketch of the Skogfoss area. Lille Mennika was a tributary running into the Pasvik river. A dam was built there, the Mennika dam, which is more than two kilometres inside Russian territory. (Pasvik Kraft’s archives)

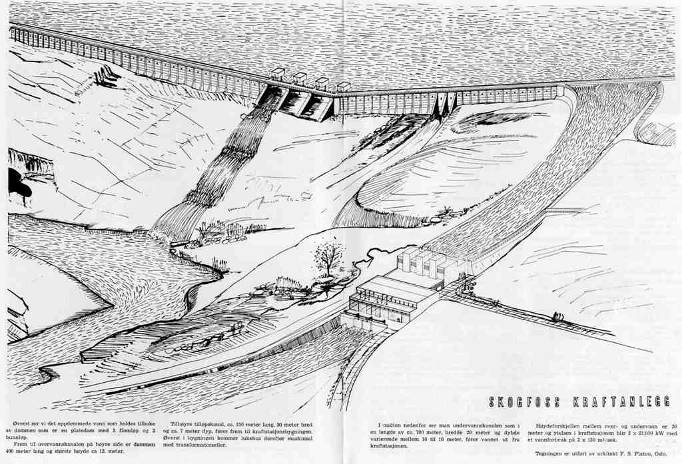

Skogfoss power station. The power station’s shutters are on the Russian side of the border. Bearing in mind that Skogfoss power station was built at the height of the Cold War between East and West, that is impressive. (Drawing: Architect F.S. Platou, Oslo. Varangverket, no. 2 1962)

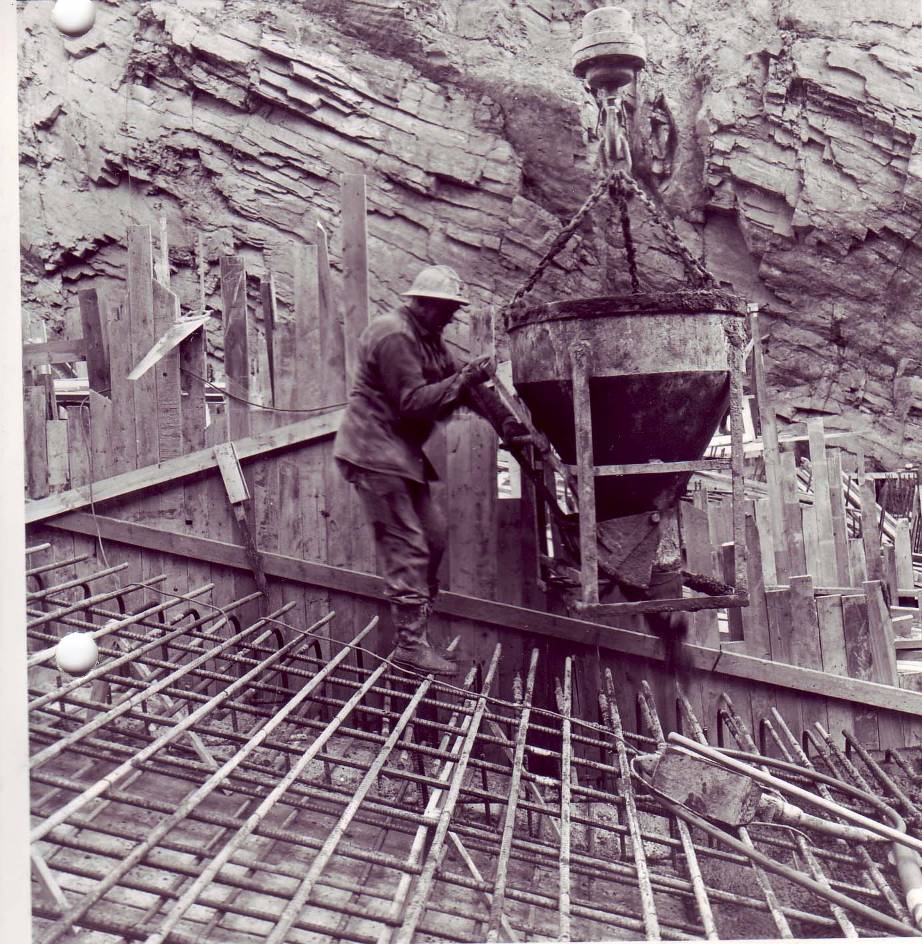

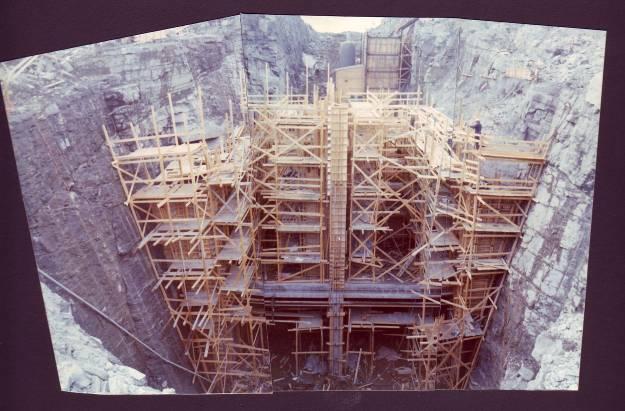

Enough work for concrete reinforcers and concreters. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger’s archives)

Many tonnes of concrete went to build the power station at Skogfoss. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger’s archives)

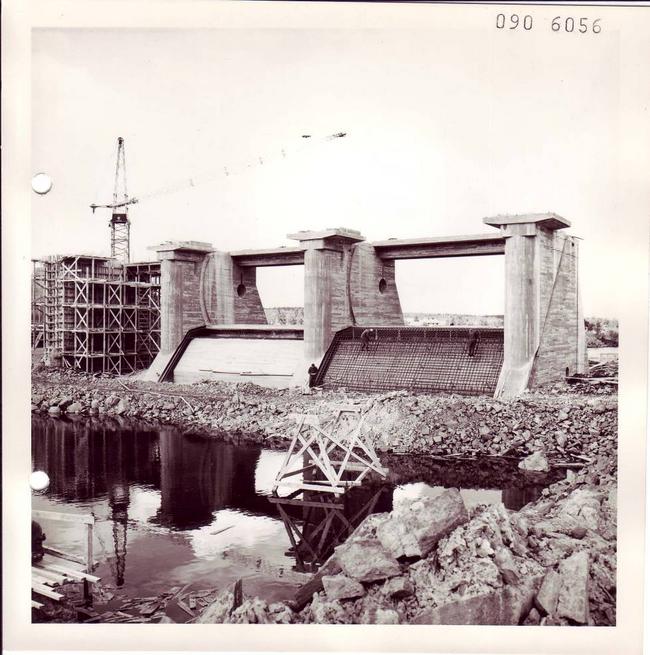

Work progresses. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger’s archives)

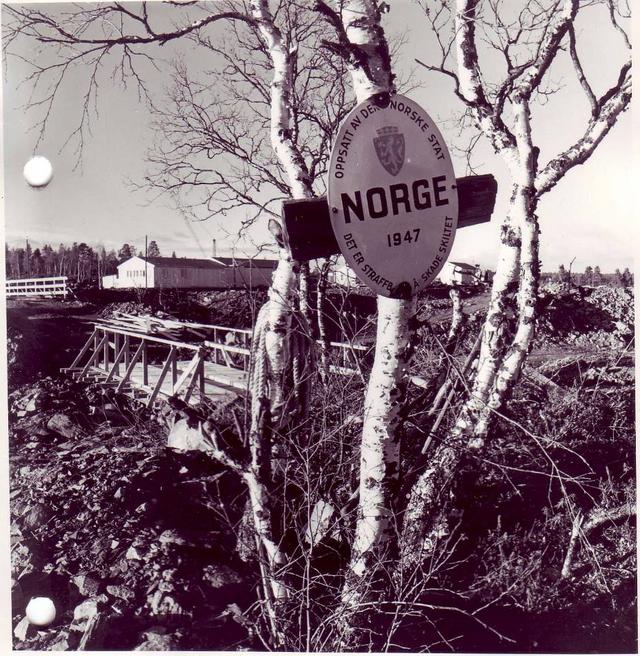

Original marking of Norwegian territory, with the hutted camp at Skogfoss in the background. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger)

The finished result. The dam at Skogfoss today. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

The dam at Skogfoss, parts of which are in Russia. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum) |

|

The proposal to develop the Melkefoss falls was highly controversial. The development of the last waterfall on the Pasvik river triggered a huge local reaction, with public meetings, petitions and protest actions of various kinds. Some protesters attempted sabotage during the development period. The local population were unwilling to let the last waterfall go without a fight. Why development?In 1974, the power company Sameiet Skogfoss Kraftverk issued a press release concerning Melkefoss:

The estimated costs were NOK 105 million, and the companies A/S Sydvaranger and Varanger Kraftlag A/L invested half each. The construction work began in July 1976 with the engineering firm Ingeniør F. Selmer as the main contractor. The power station at Melkefoss came into operation two years later, at a total cost of NOK 130 million. And so the last waterfall on the Pasvik river was developed − but not without a fight and opposition from the local population.

Development licenceThe Pasvik Agreement of 18 December 1957 had apportioned the river’s waterfalls between Norway and the Soviet Union. Norway got the middle section of the river and the plan was initially to develop Skogfoss and Melkefoss as a combined project. Questions were raised as to whether the licence from 1958 was still valid in the 1970s. The Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) said yes to a separate development of Melkefoss, while the Ministry of Industry said no because social conditions and questions concerning nature conservation and the preservation of natural resources had changed. They also took the view that this time the application concerned Melkefoss alone. The matter had to be considered afresh and on 25 June 1976 the Government decided that Sameiet Skogfoss Kraftverk should develop Melkefoss. Save Melkefoss CampaignA large proportion of the population of the Pasvik valley were against the development of the last waterfall in the river. The Save Melkefoss Campaign was fought with petitions, public meetings, newspaper letters and articles and lobbying of politicians. 1,202 signatures were collected within the municipality. The campaign was led by Olav Beddari, the long-serving principal of Skogfoss school who was also engaged in nature conservation and preserving traditional culture. Public meetingsThe Save Melkefoss Campaign organised several public meetings in the years prior to the development of Melkefoss. At a public meeting on 7 May 1975 a resolution was passed, which included the following statements:

Campaign leader Olav Beddari“For me, there were three important arguments for preserving Melkefoss: nature conservation, fishing, and using Melkefoss for tourism. We were of course accused of local patriotism, and for us the Pasvik valley was naturally important. We fought for the local community,” recounted the leader of the Save Melkefoss Campaign, Olav Beddari. “Anyone who has ever heard the roaring of the falls will perhaps understand our fight.” Fight against superior forces“I realised after it was all over that our struggle to preserve the last waterfall in the valley had been futile. We were fighting against superior forces, and I believe the whole thing had been decided in advance. A/S Sydvaranger was of course a giant at that time, and it usually got what it wanted,” explained Olav Beddari. “But we were inspired by others who fought. And we can at least say that we didn’t give up Melkefoss without a fight!” The role of local politiciansSør-Varanger municipal council debated the proposed development of Melkefoss several times in 1975-76, and their demands in connection with the development changed somewhat over time. Eventually the council recommended that a development licence could be issued if:

Demands were also put forward for fish ladders to be built at Boris Gleb, Melkefoss and Skogfoss, and for the road to be improved all the way to Vaggetem. The local politicians wanted to see the greatest possible benefit accrue to the municipality and the people of the Pasvik valley. The great majority of politicians, from the Labour and Conservative parties, were in favour of the development. |

LicenceIt was decided by Order in Council of 25 June 1976 that Sameiet Skogfoss Kraftverk should be granted a licence to build and operate the power plant Melkefoss Kraftverk in accordance with the report that had been drawn up and the following conditions:

No mention was made of the municipal council’s demand for a salmon ladder at Boris Gleb and, stated the Ministry of Industry when granting the licence application, the licensee, Sameiet Skogfoss Kraftverk, could not be responsible for the costs of improving the road up to Melkefoss. With that, the licensee could start work on developing the last waterfall in the Pasvik river.

There were several acts of sabotage during the construction period. Putting sugar in the petrol tanks of machines was one way of doing it. No-one ever found out who was responsible. “There was a policeman at my door after it was discovered, but I was away to the south,” recounted Olav Beddari. “It was perhaps natural for the police to want to talk to me, but we were trying to influence matters in a completely different way. It was probably some youngsters who were behind it.” (Sør-Varanger Avis, 10 July 1976)

Sør-Varanger Centre Party was one of several political parties in the municipality that were against the development of Melkefoss. The party believed that a total development of the Pasvik river would be extremely disadvantageous and that other river valleys should be used to contribute to the hydropower development project. They were also concerned about the fish, climatic changes, farming and bird life. (Facsimile from Nationen, 19 March 1974)

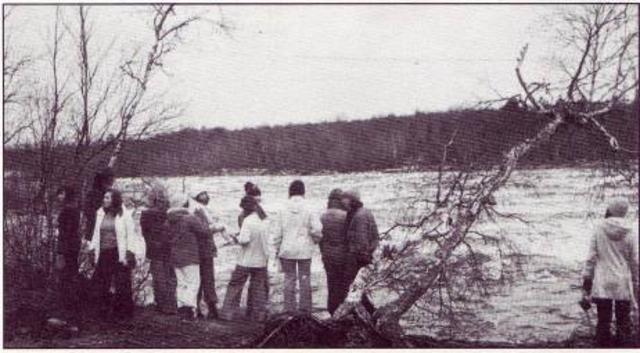

A group of students from Svanvik Folk High School at Melkefoss in the autumn of 1976. The hydropower development had started up at that time. Several of the students worked actively to preserve Melkefoss. There are few pictures of Melkefoss from after the war; most people complied with the photography ban along the border. (Photo: Svein H. Sørensen)

The development of the power station by the Soviet border led to a lot of contact between the border authorities. The dam at Melkefoss was built in the Soviet area by Norwegian workers. A provisional bridge was also set up. (Finnmarken, 23 July 1976)

Hutted camp at Melkefoss during the construction period. The development was important for employment. Some people think that even though the building of Melkefoss provided many jobs during the construction period, the Pasvik valley got too little back to compensate for the loss of the last waterfall. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger’s archives)

The channel is over 20 metres deep. At the height of the construction period there were over 130 people employed here. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger’s archives)

The management take their lunch in the hut. (Photo: A/S Sydvaranger’s archives)

Melkefoss power station, with the old riverbed in the background. The border with Russia goes roughly in the middle of the old riverbed. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

The channel at Melkefoss on a late autumn evening. Many anglers find their way here to try to hook a big trout. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum) |

|

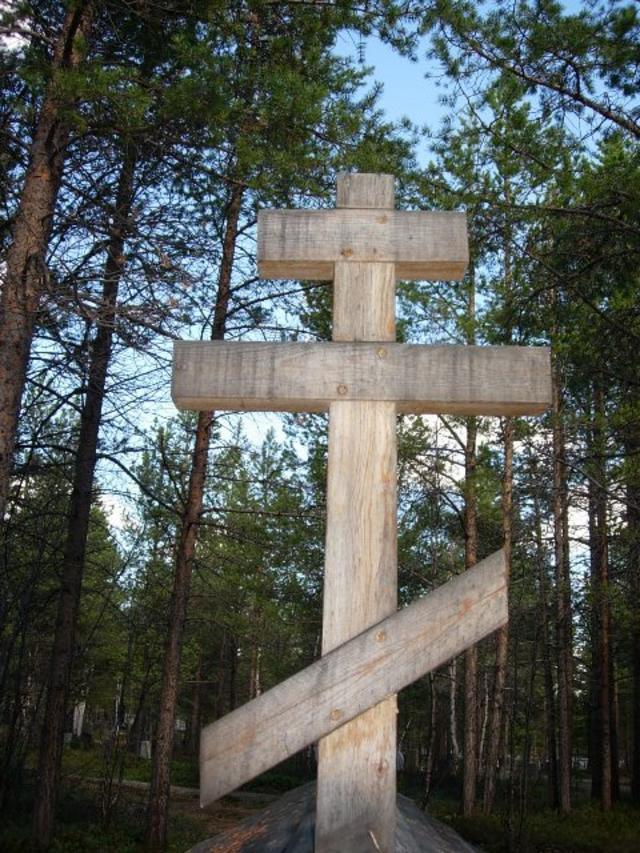

The development of the Pasvik river had many positive ripple effects: jobs, revenues and a more secure electricity supply. The river had to be dammed and the water would rise. For many in the valley, this would have huge consequences. The East Sami burial ground at Vaggetem would be submerged. Several farms would have to be abandoned as a result of the damming of the river and the development of Skogfoss. Land under waterAfter it was decided to develop the Norwegian-Russian section of the Pasvik river, work began on surveying where the river would run. The building of hydropower plants demands the construction of large dams, enabling the water to be collected and the volume of water to be regulated. It also means that the water in the river will rise. It was estimated that the water in the Pasvik river would rise by up to nine metres, and consequently that large land areas would be submerged. Burial place movedThe East Sami had lived along the Pasvik river system for centuries, and their right of use of the area was sacrificed to the desire of the national states to mark their borders and territory. The East Sami burial ground was left in peace up until the end of the 1950s, when the Pasvik river was first dammed. The East Sami of the Pasvik siida had buried many of their dead on the island of Gravholmen in the Pasvik river. According to the plans, the burial ground in Vaggetem would be submerged when the dam was built. The remains of 31 East Sami were moved to the churchyard on “Hill 96”. The last journeyThe old population of the Pasvik valley were not allowed to rest in peace on Gravholmen. The remains of East Sami who had been buried there between 1500 and 1900 were exhumed and moved. The last journey for the East Sami dead from the Pasvik siida on Gravholmen was a fact. The work was headed by the then Senior Curator at Tromsø Museum, Povl Simonsen, in the summers of 1958 and 1959, at the request of the power company undertaking the development. Approximately 6,000 years of history were uncovered, including tools dating from the ancient stone-age Komsa culture and two hunting cabins that were about 2,500 years old. Burial customsThe graves were in three layers, one on top of the other. The East Sami moved their settlements at intervals of approximately 70 years. The bottom layer of earth bears witness to the old, pagan religion, while the second layer shows evidence of Russian Orthodox burial rites, followed by a third layer when the use of coffins had been introduced. On top of the coffin was built a little log house with a cross on the roof, and inside the coffin were laid gifts for the deceased, often a wooden spade and an axe. Some individuals were buried in a hollowed-out tree trunk, or a reindeer sleigh or a komse (Sami cradle), and a baby was found buried wrapped in birch bark. They rest now in a corner of the churchyard in Pasvik. Their last journey is over. Gravholmen was not submerged by the waters after all; it proved unnecessary to move the graves. Surveying workIn the summer of 1956, Birger Erlandsen was working for the firm of surveyors Nerdrum Oppmåling, who were contracted to mark where the river waters would come after the damming in connection with the hydropower development. “There were 3-4 gangs of us who went from Grensefoss to Boris Gleb. My job was to clear the sighting path for the surveyor’s level, so they had a good sighting for where the next point for the new river bank would be,” says Birger. “I cleared trees, and the assistant surveyors put down red poles. It was a fine job. There were several men there from the Pasvik valley, including Olav Emanuelsen, Viggo Beddari, Håkon Håkseth and Viggo Paasche,” adds Birger. Damming submerged homesBirger’s family settled at Krokvik at Langvannet (Pitkäjärvi in Finnish) by the Pasvik river in the mid-1930s. The land was cleared for farming and the eight siblings grew up on a farm by the bank of the river. In 1956 the family were told they would have to leave their farm, along with the occupants of seven other farms in the Langvannet area. “I didn’t think that much about it at the time,” explains Birger. “I was only 18. I remember that it wasn’t talked about at home. They weren’t used to complaining. But we’re talking about my mother and father’s lifework.” Discretionary assessment“A committee made a discretionary assessment of the property, but I think my parents feared the threat of a second assessment. That would mean the amount of compensation might be even less,” says Birger. “I’ve thought a lot about it in the years since then; why didn’t they get more in compensation? They were told they had to move, and that generation had a great respect for the authorities. Apparently no-one protested,” recounts Birger Erlandsen. Abandoned farmsAs a result of the development of the falls at Boris Gleb and Skogfoss, large areas of agricultural land were lost. A total of 53 farmers lost cultivated land. Some farms were completely destroyed, buildings were moved and several farmers and their families settled in other parts of the valley. Most were getting on in years, and the farms they had built up before the war would be totally destroyed by the damming. For the majority, there was no point in starting up farming again. |

The Erlandsen family’s house on the old Krokvik farm. Birger Erlandsen’s parents, Nils and Johanna Erlandsen, moved with their family from the farm in 1960, and lived in huts and outhouses while the farmhouse was taken down and re-erected a few hundred metres away. “Mother and father didn’t start up farming again, they were too old,” says Birger. (Photo lent by Birger Erlandsen)

The forest was cut down by Langvannet; the water was expected to rise by about nine metres. Birger Erlandsen lived with his family by Langvannet. He was part of the workforce that cleared the forest. (Photo lent by Birger Erlandsen)

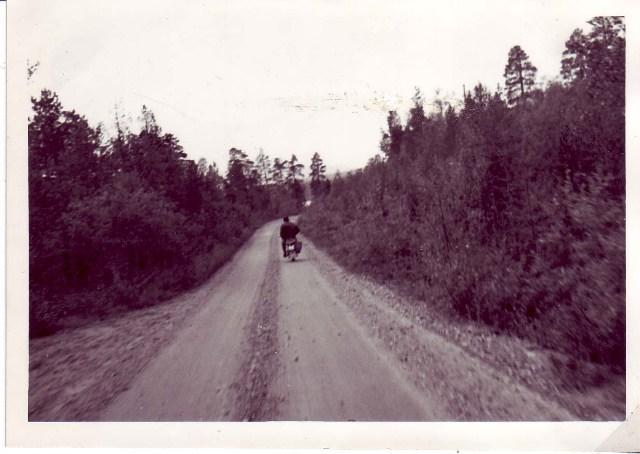

The road by Langvannet before it was dammed. The road was given a new alignment route. (Photo lent by Birger Erlandsen)

The old fence posts on Erlandsen’s old farm, Krokvik, sticking up out of the water. Langvannet is like a large lake, and forms part of the Pasvik river. Birger and his brother-in-law, Per Emanuelsen, took us on a special boat trip over the land that disappeared. “There were several meadows, headlands and bays here,” explained Birge, pointing out over the large Langvannet. “Now it’s completely changed. Enormous areas have been submerged.” (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

At one of the islets in Langvannet in the Pasvik river. Per stops the engine and Birger points down at the surface of the water. “Not far away are the foundations of the house I grew up in. We can see them when it’s not too windy,” says Birger with sadness in his voice. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

The old sauna was also moved when the Erlandsen family had to leave their farm. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Memories under water. Cloudberry marshes, landing places, fields and places where once people could get a good catch of fish are now under water as a result of the damming of the river. “Before, we could walk dryshod to the islet over there,” recounts Birger Erlandsen. “We always used to celebrate Midsummer Eve there. And we went swimming, no matter what the temperature was! Now the islet’s in the middle of the river, and there are several hundred metres to the river bank.” (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

The Orthodox cross on the East Sami tomb in Svanvik churchyard. The tomb contains the remains of 31 East Sami from the Pasvik siida. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Gravholmen before excavations began in 1958. According to the plan, the old East Sami burial ground would be submerged as a result of the development of Skogfoss. But the burial ground did not end up under water after all. (Photo: Povl Simonsen, Varangverket no. 4. 1963) |

|

The hydropower co-operation between Norway and Russia is still in existence. Power companies in Norway purchase electricity from Russia and the two countries also collaborate on other energy projects. Meetings are held annually between representatives of the hydropower authorities in both countries. The Pasvik river system is administered in collaboration between the three neighbouring states of Norway, Russia and Finland. Co-operation with RussiaThe co-operation with Russia and the former Soviet Union has been in existence since the end of the 1950s. Already in the 1960s, Norway was buying «Russian electricity» from the power plant in Boris Gleb. Today, the co-operation has been developed further and includes work to generate windpower on the Russian side. The Cold War that developed between East and West after World War II did not change the good relations between the players in the hydropower industry on the Norwegian and Russian sides of the river. Electricity from Russia“Russia has been helping to secure the electricity supply in East Finnmark for several decades, and for that reason a good, constructive working relationship has been essential and of interest to both the Russian power company Kolenergo and the Norwegian power company Varanger Kraft. The relationship has been highly conducive to a shared understanding of modern energy and environmental co-operation,” affirmed Tor Arne Pedersen, Managing Director of Varanger Kraft, in 2005.

The ROSELNOR ProjectThe Barents Sea region is an extremely interesting area in terms of generating renewable energy, such as hydropower and windpower. “The ROSELNOR Project aims among other things to increase the value generated in the Pasvik river system. The project has created a positive working relationship and greater openness between the Russian, Norwegian and Finnish parties,” explains Tor Arne Pedersen. “The focus of the project is to create a better environment for the area around the Inari lake, as well as to boost commercial power production in the river system.” The environment around the Inari lakeThe development of the Pasvik river led to big changes around the Inari lake. “Increased capacity and better regulation will help reduce the risk of flooding and erosion damage in the area around the Inari lake,” says Varanger Kraft’s Tor Arne Pedersen. “It will also reduce the risk of losses due to flooding and will enable us to increase production in winter. We have been looking in principle into the possibilities of limiting the flood peaks in the spring in the Inari lake and the Pasvik river system by increasing the amount of water we draw off early in the winter.” WindpowerVaranger Kraft have furthermore expanded their collaboration with Kolenergo to develop windpower on the Kola peninsula. The collaborative project is an extension of the ROSELNOR Project, and is examining the potential for windpower in the area around Teriberka on the Kola peninsula. |

Revenues for Sør-Varanger municipalitySør-Varanger municipality receives approximately NOK 1.2 million annually in licence fees, which are apportioned in the ratio 2:1 between a general business development fund and a primary industry fund. Most of the money from these funds is used to provide investment support for private-sector businesses, preferably to establish new businesses. In the past few years some of the cash has been given as operating subsidies to business-oriented institutions in which the municipality is investing: tourist information, marketing, and the start-up of Kirkenes Næringshage, an association of local businesses. Electricity to sellSince 2004 Sør-Varanger municipality has also been able to purchase a share of the electricity generated under the licence, for its own use or to sell. “It is not yet clear how much this will bring in the way of revenues, but it will definitely be important for the municipal economy,” said Tone Hatle (Conservative party), leader of the municipal council, in autumn 2005. The municipality’s share of the dividends from Varanger Kraft in 2005 was NOK 6.2 million.

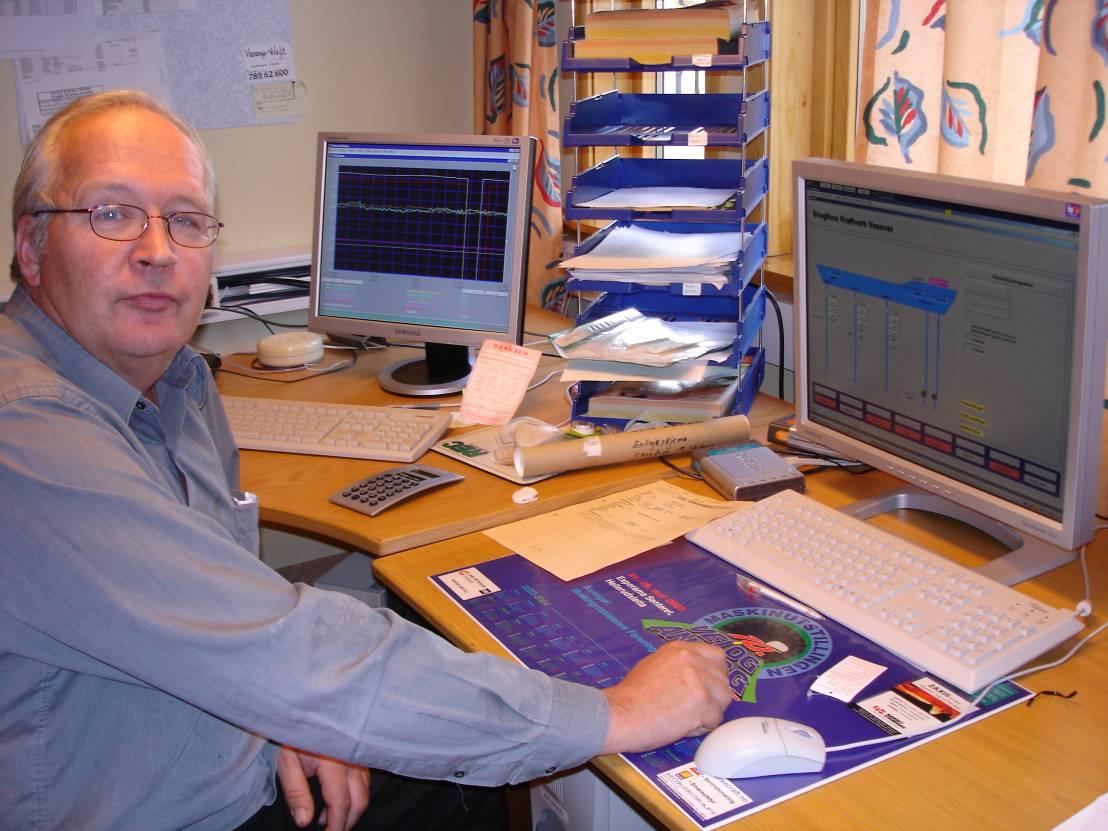

Production engineer Arild Edvardsen is responsible for technical watercourse operations and his job is to monitor the electricity generation in Pasvik Kraft’s premises outside Kirkenes. “Before, the duty engineers lived near the power station at Skogfoss and had alarm clocks in their sitting rooms,” says Edvardsen. “Now we are on 24-hour home duty, and can receive alarms on our mobile phones so we can respond at short notice. Using our duty PCs, we can sit at home and adjust the load up and down depending on the water level.” (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Power lines from the Melkefoss, Skogfoss and Boris Gleb power stations. The Russian power station in Boris Gleb also supplies electricity to Norway. In the autumn of 2005 the electricity was sold to the TromsKraft power company. (Map: NVE)

Network chief Leif Edmund Jankila, project director Vladimir Kiselev and managing director Tor Arne Pedersen in a meeting in Varanger in 2005. Kiselev represents the Russian energy company Kolenergo. Plans are being worked on to develop windpower in the area around Teriberka, approximately 100 kilometres north-east of Murmansk. Here the power line network has been expanded to take additional generation of 115 MW. (Photo: Varanger Kraft)

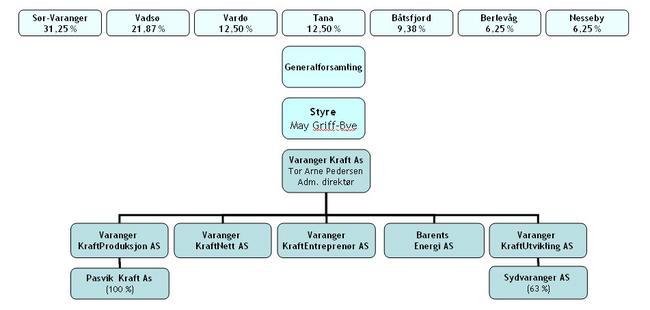

Organisation chart for the power company Varanger Kraft As. The company is owned by the municipalities in East Finnmark, with Sør-Varanger the largest owner. Varanger Kraft has undergone several structural changes over the years. Sameiet Skogfoss Kraftverk is now known as Pasvik Kraft. Sydvaranger AS was sold in 2006 to Nordberg Eiendom. (Illustration: Varanger Kraft)

On the dam in Rajakoski in Russia. From the celebrations to mark the 50th anniversary of the Pasvik power stations in the summer of 2005. Representatives from Pasvik Kraft and the Russian company Kolenergo. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

Maintenance and checks on the power stations are carried out at regular intervals. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

King Winter ensures that ice accumulates in the channel at Melkefoss. Temperatures of around -35ºC are not unusual in the Pasvik valley. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft)

The Inari lake in Finland. The development of the Pasvik river resulted in changed biological conditions in this huge lake. The regulation of the water level changed the strand zone as well as the life there. The watercourse co-operation also involves focusing on changes in the natural world and all forms of life around the Inari lake. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

A good flow of water. (Photo: Pasvik Kraft) |