The Pasvik River

One river - three states

Today, the Pasvik river forms the border between Norway and Russia. The Pasvik river valley has been and remains a meeting place for different cultures and peoples. The politics, wars and borders of the nation states have had huge consequences for the people living in the area. The Norwegian state marked its territory, and built schools, chapels, tourist stations and experimental farms. The Finnish-Russian War left its traces among the people of the Pasvik valley. The Cold War between East and West also had a big impact on life by and on the river. But Norway and the Soviet Union also co-operated on a project to develop the river for generating hydro-electric power. Today there are close relations between Norway and Russia, and there is co-operation in culture, tourism, energy and research. But crossing the border on the river is still forbidden!

|

|

|

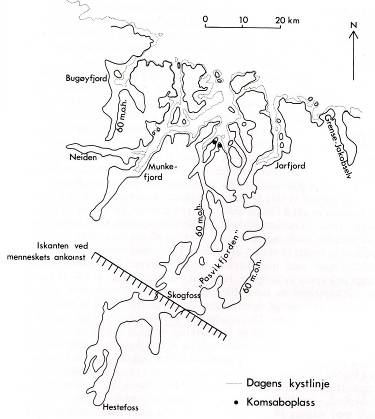

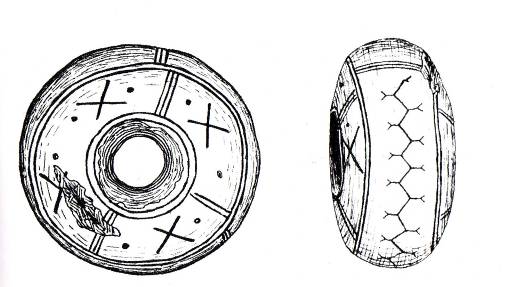

There are traces of human habitation in the area we today call Sør-Varanger, which are about 10,000 years old. Finds show that people gradually became expert in exploiting the resources of the area. Cultural traces indicate contacts with peoples in the east. The Ice AgeSør-Varanger was completely covered by ice during the last Ice Age. By the end of the Ice Age, in about 10 000 B.C., the coastline was completely free of ice. Inland areas were ice-free in about 7000 B.C. With the melting of the ice, both the land and the sea rose. The sea level rose because of the meltwater from the glaciers, while the land rose because the pressure exerted by the heavy ice had gone. The vegetation that developed provided good living conditions for wild reindeer. In the sea, warm ocean currents created a good environment for fish, seal, whales, seabirds and other marine life to thrive. It is in this setting that we find the first traces of human activity. The people who came here were hunters and their chief game was wild reindeer, but they also harvested the rich resources of the sea. Early Stone AgeThe oldest settlements in Sør-Varanger date from the Early Stone Age, which lasted from about 10 000 B.C. to 4500 B.C. We call this period the Stone Age because the objects that have been found are chiefly of stone. From the last part of the early Stone Age some objects of bone have been found, and we think that bone, together with wood and animal horn, were important tool-making materials throughout this period. Settlements, graves, and tools for fishing, trapping and hunting have been found in Sør-Varanger. The people who lived here had a semi-nomadic way of life, which means that they moved between particular areas according to the seasons. They went wherever there was a good supply of resources. They were probably able to move around easily as they lived in light-weight tents made of animal hide that were easily transportable. Last Stone AgeIn the Late Stone Age (c. 4500-1800 B.C.) the climate changed, and the forests that had developed in the Early Stone Age began to disappear. The vegetation gradually became similar to what we know today. The sites, or ‘tofts’, of settlements found along the coast are larger and more evident than those from the Early Stone Age, indicating that the settlements were more stable and the orientation towards marine resources had been strengthened. At the same time, the people living in the inland areas of Sør-Varanger were highly mobile. There are many traces of the people who lived in the Pasvik valley. There are rich findings from the Late Stone Age, with many beautifully decorated objects of bone and animal horn. Stone tools were still important, but the tool-making techniques differ from those of the Early Stone Age. Tools were made in more fine-grained materials such as slate and greenstone. Both the change in tool-making techniques and the use of new kinds of rock indicate what was perhaps the biggest difference between the Early and Late Stone Ages, which was increased contact with other peoples. Early Bronze AgeThe Early Bronze Age (1800-0 B.C.) is characterised by a more uniform use of pottery between coastal and inland areas. The differences between coastal and inland settlements became fewer. In addition to stone, wood, horn and bone there are some tools of copper and bronze. Most are from the end of the period. The last 1,000 years of the Bronze Age era show traces of major social, cultural and economic changes, and many people believe that it is during this period that the Sami emerge as a defined ethnic group. Many of the features that are viewed as typically Sami, including types of settlement and burial customs, emerge clearly at this time. In Pasvik, we see an increase in the number of settlements and a distinct type of pottery develops, called Pasvik pottery. Sami Iron Age and the Middle AgesIt is difficult to establish the ethnicity of a culture based on archaeological material alone. There is nevertheless little doubt that the people who lived in Sør-Varanger after the year 0 B.C. are the forefathers of the present Sami population of the area. New features include reindeer herding, sheep-keeping, woollen clothes, new decorative styles in bone carving and embroidery, and the use of iron. We also see changes in religion and politics. Contacts with other peoples, and other places, increase. Gradually, as tame reindeer herding spread, the seasonal migrations between inland and coastal areas changed. Unlike previously, the winters were now spent inland and the summers at the coast. Reindeer herding and husbandry changed from a system with each family keeping reindeer for slaughter, hides and meat, etc., via intensive reindeer husbandry with many owners and small herds, to full nomadism in about the 1500s. |

|

|

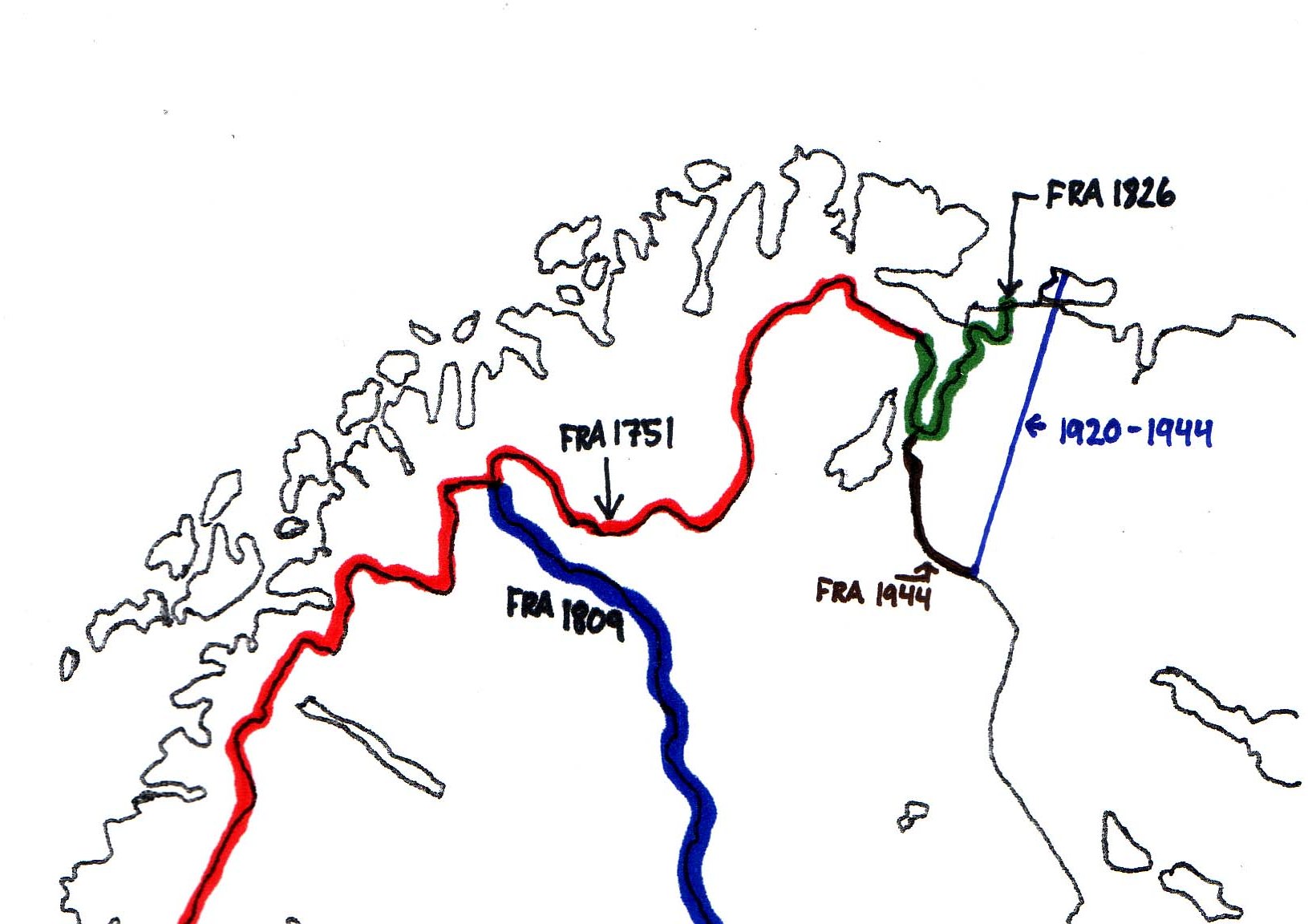

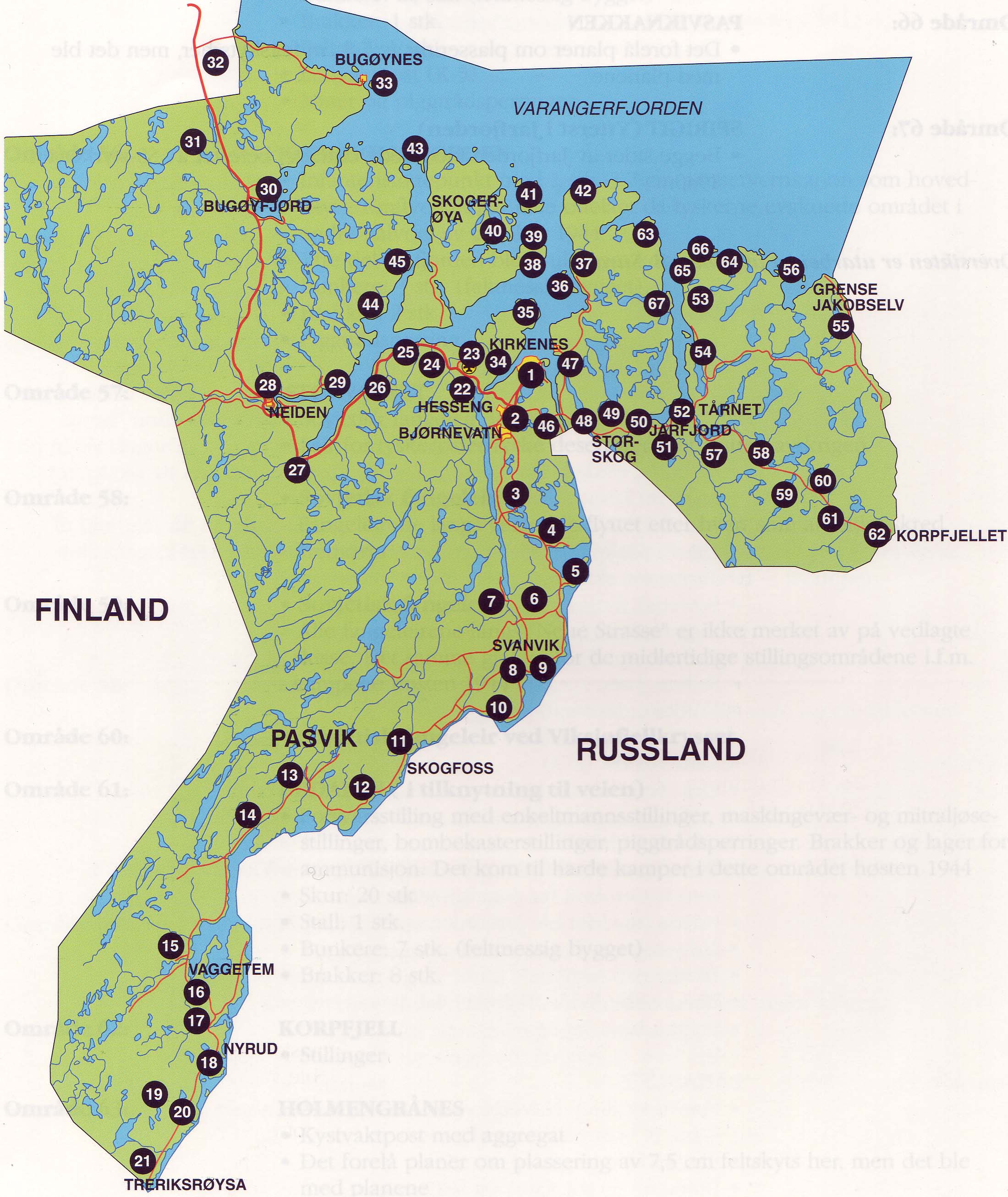

In 1826, the border was drawn between Norway and Russia, and the Sør-Varanger area became part of Norway. The politics, wars and borders of the nation states had huge consequences for the people of the area. Old local and regional borders were of less importance. Contact across the borders continued between the peoples in the border area between Norway, Finland and Russia. 1200sNegotiations on the rights to the White Sea. 1751The border between Norway and Sweden was finally established. Norway took over Kautokeino, Karasjok and Utsjok on the north side of the Tana river (Polmak). The rest of the communal district stayed in the ownership of Sweden-Finland. The Lapp Codicil was part of the border treaty and was intended to secure the rights of reindeer-herding Sami to move across the national borders. 1809Sweden was forced to surrender Finland to the Russian Tsar. Finland became a separate Grand Duchy in Russia. 1814Norway separated from Denmark and entered into union with Sweden. Norway got its own constitution on 17 May in Eidsvoll. The area we today call Sør-Varanger was not part of Norway(!), but part of the communal district of Norway-Russia. 1826The border between Norway and Russia was established. The remainder of the communal districts south of Varanger were divided between the two countries. The Enare (or Inari) lake was defined as Finnish and left the communal district. Sør-Varanger became part of Norway. The border cut through the old East Sami siida areas. 1852The Norwegian-Finnish border was closed for the movement of reindeer. This had consequences for reindeer-herding Sami, as new grazing lands had to be found. It was however difficult for the authorities to enforce the agreement along the border. 1905The union between Norway and Sweden was dissolved. Norway became an independent state. 1920Finland and the Soviet Union signed the peace treaty in Dorpat. Petsamo-Suenjel became a Finnish area when the border was drawn between Soviet-Russia and Finland inasmuch as Finland was independent. Russia was now no longer a neighbour of Norway. 1939The Finnish-Russian War between Finland and the Soviet Union. Finland had to surrender parts of its territory to the Soviet Union. 1940World War II begins. Norway is occupied by Germany 1944Finland’s border with the Soviet Union was changed. Petsamo and Suenjel became Soviet territory. Norway acquired the Soviet Union as its neighbour in the east. Movement across the border was strictly limited. Sør-Varanger was liberated by the Red Army as the first area to be liberated in Norway. 1991The Soviet Union is dissolved. Russia becomes an independent republic. |

|

|

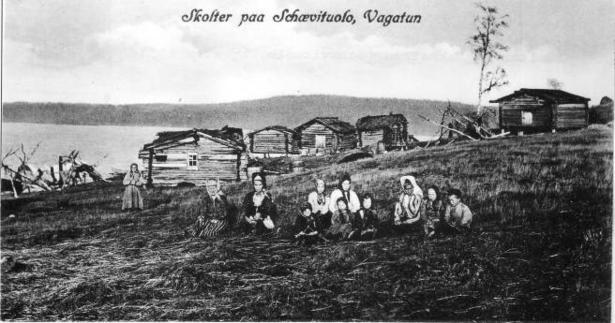

The East Sami are also known as “Skolte Sami”. The East Samis’ name for themselves is Nuorttalazzak. They had the Pasvik area virtually to themselves right up until the 1800s. Many North Sami, Enare Sami, Norwegians, Finns and Russians settled in the areas around the Pasvik river system. The drawing of the border, and the politics and wars of the nation states, would have great significance for the East Sami, the indigenous people of the area.

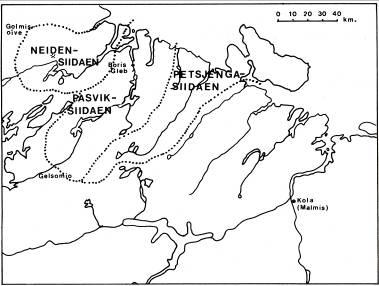

SiidasThe East Sami were organised in siidas. The siida system is also common in other Sami societies. A siida consists of several families who together own and use a delimited geographic area. The siida is also the name of the area. For some parts of the year, the families would be spread over the entire area. In the winter time, all the families would be gathered in the winter settlement, and there was time for socialising. East Sami siidasThe East Sami population consisted of such siidas. The drawing of the border in 1826 between Norway and Russia cut right across the siida areas. Three siidas were inside the Norwegian-Russian communal district:

The East Sami in Pasvik became Russian citizens in 1826, although those belonging to the Neiden siida remained Norwegian.

Seasonal migrationThe East Sami lived in a hunters’ culture, pursuing a semi-nomadic way of life. The East Sami had several settlements in the Pasvik valley and by the fjords in Sør-Varanger. They lived where there was best access to resources. In the spring and summer they lived by Bøkfjorden and Jarfjorden, where there was a plentiful supply of salmon, cod and coalfish. They took the animals they owned with them out to the fjords. In the autumn and winter they lived chiefly along the Pasvik river.

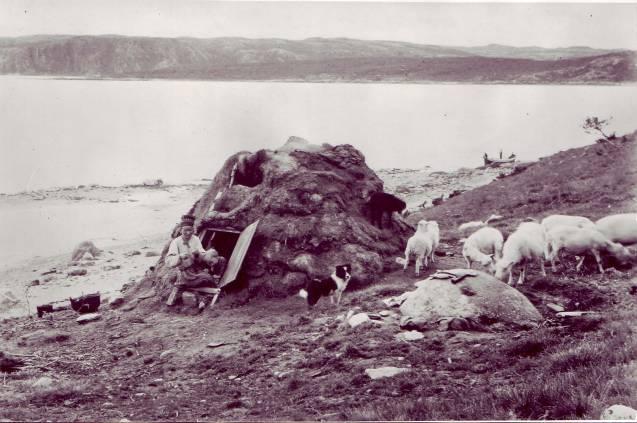

Gamme (Sami turf hut) in the Pasvik valley. The man’s headgear appears to be a typical East Sami man’s cap with fox-fur trim. For many of the people of the Pasvik valley, the gamme is a familiar dwelling place. The first thing many people built when they settled in the valley was a gamme. The gamme was also used by reindeer herders and forestry workers, or to provide shelter on fishing trips. (Photo: Ellisif Wessel. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

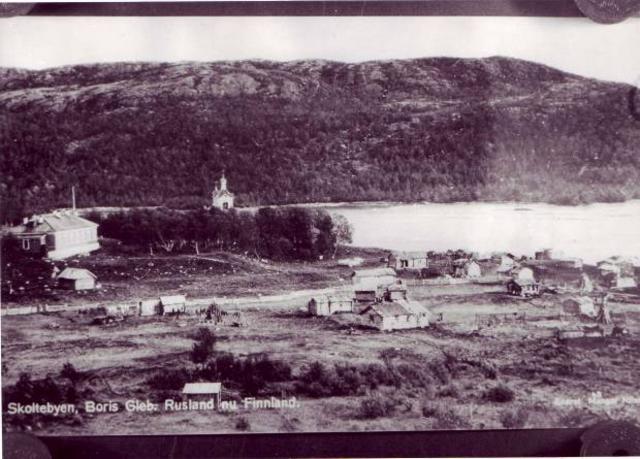

“Skolte Sami” town. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

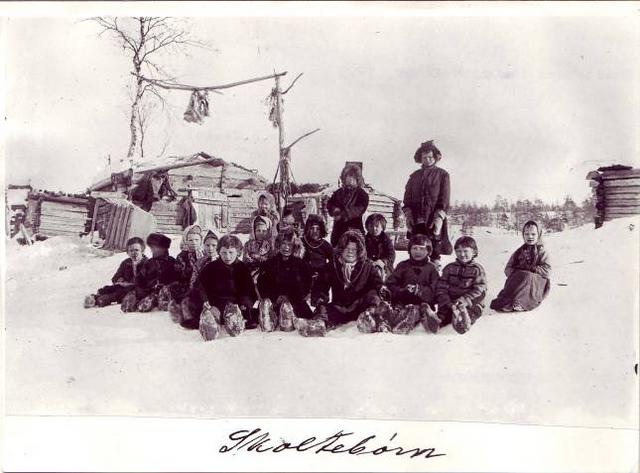

“Skolte Sami” children. (Photo: Ellisiv Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

East Sami women in Boris Gleb. There are many old photographs of East Sami people, but unfortunately we do not always have their names. (Photo: Unknown. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Pearls can be found in about one in every thousand river mussels. These freshwater pearls have been sought after through history by kings, princes and clerics from all over Europe. In Pasvik stories are told of the pearls having had an important function among the East Sami as both ornamentation and a medium of exchange, and it is said that a good pearl could be exchanged for two reindeer. (Photo: Paul Aspholm, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

A stabbur (storehouse) at Tårnet in Jarfjord. The story goes that the stabbur came from Boris Gleb in the early 1920s. The East Sami are said to have used it in payment for fish. The stabbur is said to have been transported here by boat. The East Sami had fishing rights in the Jarfjord up until about 1900. The stabbur has been restored and stands on Jenny Dørmænen’s property. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

The Pasvik river was in many ways the life nerve for the people of the Pasvik siida, who had boathouses and homes along the river. To the right in the picture we see Sallasj and Roman Afanasieff. In 1902 the boathouse stood at Kattalombola directly above Kobbfoss. Like several East Sami in the Pasvik siida, Afanasieff settled permanently in Boris Gleb. (Photo: Ellisif Wessel. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Tiina Sanila singing laud. Laud is the traditional song of the East Sami. Sanila is from the Sevettijärvi area and mixes old traditions with modern sounds and rhythms. She has released several laud on CD. Tiina is wearing the traditional East Sami cap worn by unmarried women. (Photo: Tor Sandø, Sør-Varanger Avis)

East Sami man’s cap with fox-fur trim. The red patch has been sown on to make the man more visible in the forest while hunting. (Photo: Sør-Varanger Museum) |

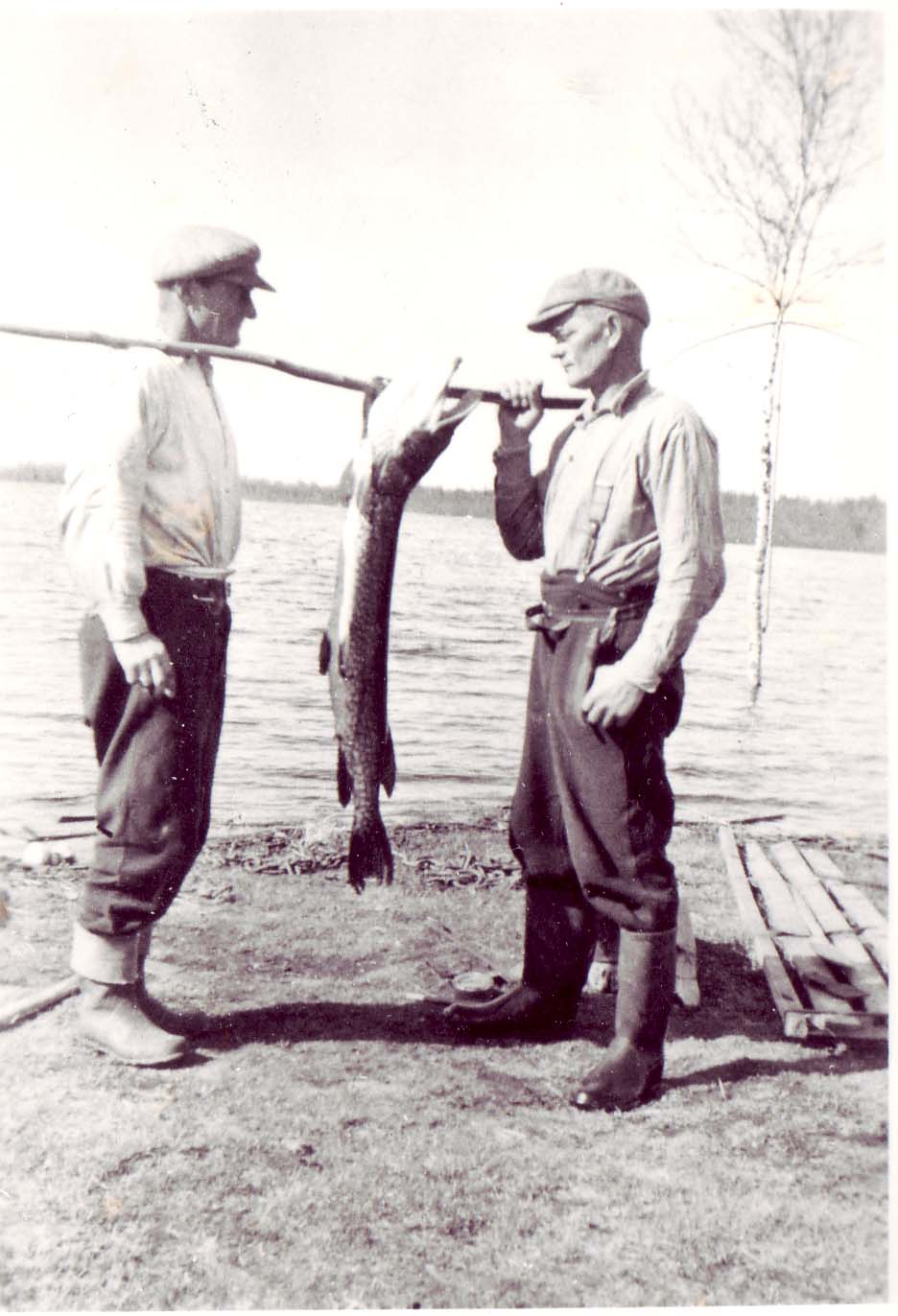

LivelihoodsFisheries were important for the East Sami, and this applied to both freshwater and sea fishing. Nature was the most important source of food. Many East Sami families kept some sheep and reindeer. The reindeer provided meat, hides and bone, but were also important as a means of transport. The East Sami made use of nature’s resources and moved according to where those resources were available. Fishing in Norwegian FjordsThe East Sami in the Pasvik siida lost their fishing rights in the Norwegian fjords Bøkfjorden and Jarfjorden in 1924. They were at that time living in Finland. Norway and Finland agreed that Norway could purchase the fishing rights for 12,000 gold crowns. The East Sami had no real possibility of refusing this. Norway was not interested in having the Pasvik siida in Norwegian fjords. Borders and warsThe culture of the East Samis became a victim of the politics, border regulations and wars of the nation states. Their old ways of life with seasonal settlements and the siida system had no place in a modern world. Finland developed the Petsamo area and pressure on the East Sami increased. It became difficult to maintain the seasonal migrations. Many East Sami settled permanently in Boris Gleb. After World War II, the area became part of the Soviet Union, while the East Sami in the Pasvik siida remained Finnish citizens.

MigrationMrs Ryeng, the widow of forest ranger Ryeng, told the archaeologist Povl Simonsen in 1959 that Nakholmen on Vaggetem was settled from about 1 August and until the first snows fell. After that the East Sami went south-east to Russia for ice-fishing for about a month. From there they continued to the Svanvik area for the winter, and then down to Boris Gleb at Easter. Following that they went to the fjords to fish.

The East Sami todayToday, the East Sami live mainly in Norway, Finland and Russia. Most of the members of the Pasvik siida chose to settle in Finland after World War II; the alternative was the Soviet Union. There are also descendants of the Pasvik siida in Norway. Then, as now, there were marriages across borders, countries and cultures. Many East Sami gather annually for Orthodox church services in Neiden, Sevettijärvi or Boris Gleb. On the Norwegian side, the East Sami centre is Neiden, and a service is held each year in St. George’s Chapel. |

|

“Päivä, päivä! Mitä?” Finnish is still spoken in Pasvik and many older people speak the language fluently. Finnish surnames such as Beddari, Kalliainen and Sotkajærvi are common in the Pasvik valley. The children learn Finnish at school, and there are still close ties with the neighbouring country Finland. The long marchConditions were hard in large parts of Finland in the mid-1800s. The dreams and hopes of a better life were the driving forces for those who left their villages. They left their homes and said goodbye to their parents, families and kin, probably knowing that they would never return. In the north, close to the fjords and the Ruoija (Arctic Ocean), lay the land were they would start a new life. They packed their few possessions, and began the long march to Paatsjoki (the Pasvik river) in the Pasvik valley. And they settled on both sides of the river. Fishing in the fjordsFinnish immigration to the Pasvik valley really started in the mid-1800s. Before that the Finns travelled to the fjords to take part in the fisheries there. The sea offered both coalfish and cod, and the fishing activity brought an income. The Finns who went to fish in the fjords must have discovered that in the north-east part of Norway conditions were also good for farming, reindeer herding and forestry.

Why did the Finns go to Pasvik?The fisheries and the possibilities of settling in an area rich in resources caused many Finns to leave their home country. In the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, many took their few belongings and made the long journey north. In addition to being attracted by the resources in Sør-Varanger, many left because large parts of Finland had experienced crop failure and crisis. Many communities had a surplus of population, and resources were few. All this helped hasten the immigration to the Pasvik valley and the areas around the Varangerfjord. Several legs to stand onThe majority of the Finns who settled in the Pasvik valley in the 1800s stayed. They established smallholdings, had children and lived like the other people in the valley. A patch of land, a few cattle, sheep and reindeer, fishing in the river and the sea, berries and timber from the forests provided a livelihood. Some farms had more than one family living on them. Multi-culturalIn North Finland a large proportion of the population were Sami. Many of those who left Finland came from communities where there had been a fusion of Finnish and Sami culture. Sami and Finns had inter-married, and many who went to Norway were a mixture of these two peoples. Both Finnish and Sami traditions were carried on in the Pasvik valley together with Norwegian traditions. The people who settled in the valley learned from one another how to make the best possible use of the resources.

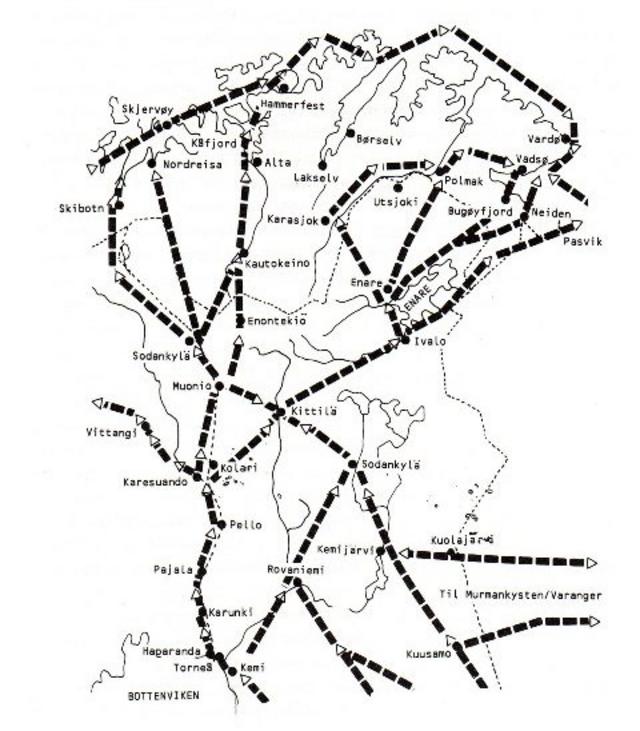

People moved away from their villages in Finland from the areas near the Enari (or Inari) lake, Sodankylä, Salla, Kemijärvi and Oulo and settled in Troms and Finnmark in Norway. Some travelled over 500 km to get to the areas around the Varangerfjord, most probably making the journey on foot − either walking or on skis. Some followed the rivers and used boats, others used reindeer or horses for transport. Many people came in the spring to take advantage of the fishing in the Varangerfjord. (Illustration: Innvandringsveiene. Einar A. Niemi: Finsk innvandring)

The Finns naturally brought their own customs and traditions from their home country. The sauna was an important element in hygiene, and it is said that the first building a Finn erects is a sauna. The sauna in the picture was built by the Beddari family at Svanvik. (Photo: Ellisif Wessel, Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

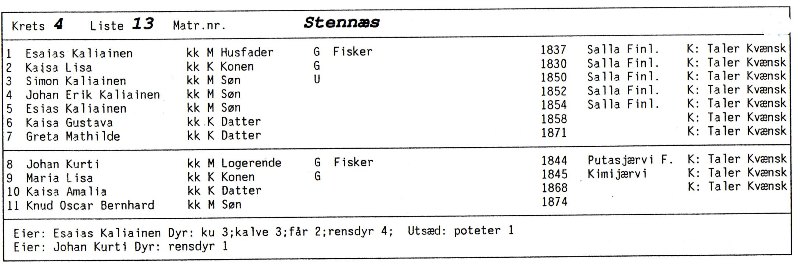

In 1875, about 200 people were living on the Norwegian side of the Pasvik valley and in the Langfjord valley. Well over half were registered in the census as Finnish-speaking. The Finns were skilled farmers, and knew how to use the land, the rivers, the forests and the resources in this harsh climate. (Extract from the 1875 population census. Registration centre for historic data, University of Tromsø)

Many of those who came from Finland brought reindeer with them, also the custom of keeping tame farm reindeer. The farm reindeer were used for transporting people, goods and timber. Gradually, most of the farms in the Pasvik valley acquired some reindeer, also the Norwegian farms. Reindeer were also an important source of food, and the skin was used for making boots, legs of boots or stockings, and moccasins. For some families, reindeer herding was their primary livelihood. In the picture we see Einar Kalliainen making the sled ready at Vaggetem. (Photographer: Unknown. Lent by Jorunn Kalliainen)

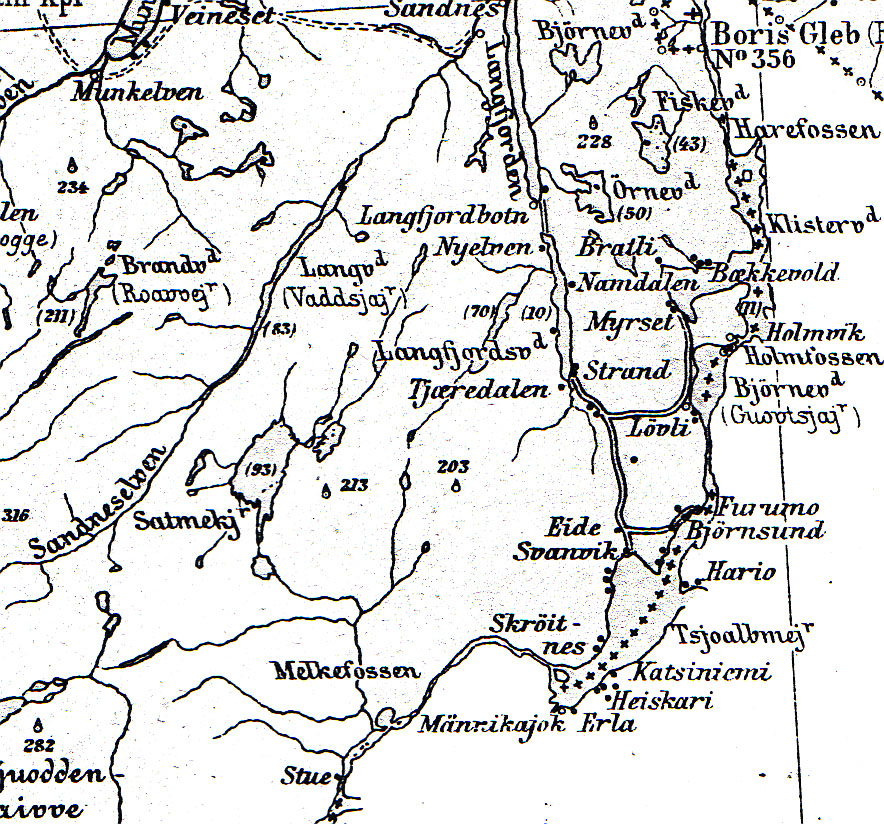

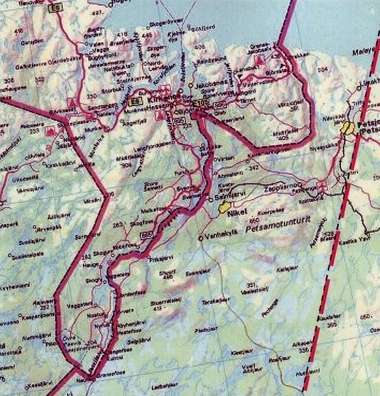

Finnish place names were common also before 1920 when Finland became the neighbouring state in the east. Many Finns lived in the area before 1920, and many settled on the east side of the river when the area was Russian. It was easier to get land in Russia than in Norway. (Map: Published by Norway’s Geographical Survey, 1906. Lent by Norwegian Mapping Authority)

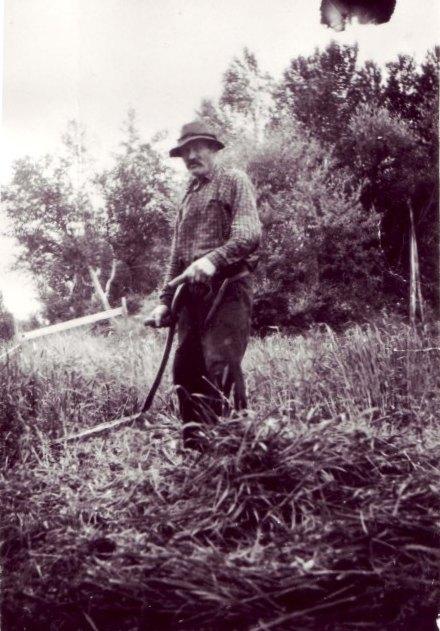

Benjamin Ollila as a haymaker in 1952. Benjamin, who lived at Melkefoss, was born in 1879 and in his youth worked as a farmhand for the merchant-farmer Aron Vartiainen in Neiden. Some Finnish immigrants were unable to buy land in Norway. For some, their stay in Norway began with a job as a servant girl or farmhand on one of the farms, while others had to take casual jobs in fishing and forestry work. (Unknown photographer. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Elin Karikoski is one of many living in Pasvik who are of Finnish origin. Her parents spoke Finnish to each other at home. “We didn’t learn Finnish at home. Mom thought it would be best if we spoke Norwegian when we started school. The parents wanted what was best for the children, says Elin.

Schoolchildren visiting Ekorn farm by the Pasvik river. There is a great deal of interest in local history in the schools. “Many children in Pasvik learn Finnish at school. The parents think it’s important for the children to learn Finnish. Many of the parents’ generation did not learn the language at home even though their parents spoke fluent Finnish,” says Elin Karikoski, who has studied Finnish as an adult and has taught Finnish to both adults and children. “It’s wonderful that the language is being taken up again. And many children without Finnish background also want to learn Finnish,” adds Karikoski. (Photo: Pasvik School)

Elin Karikoski’s maternal grandmother, Marie Elmine Ekhorn. Her maiden name was Portti and she came from the Finnish community of Salmijärvi on the other side of the Pasvik river when the area was Russian. Marie’s daughter Natalie had good contact with her first cousins on the other side of the river. It was usual to visit one another until the border was closed in 1944. (Photo: Pasvik School) |

Kven or Finnish?In the 1800s, the Norwegian authorities used the name kven for everyone who came from Finland. Gradually, the name acquired negative connotations. Kven was also the name used for the people who lived by Bottenviken. Today, many descendants of those who came from Finland and Bottenviken choose to call themselves kven. Others choose to say that they are of Finnish origin or that they have Finnish roots. In 1996, kven were recognised as having minority status in Norway. Make the area Norwegian!Initially, the Norwegian authorities took a positive view of the immigration from Finland, but then they began putting into effect various initiatives to get more Norwegians to move to the area. A roadbuilding programme was started already in the 1870s and Norwegian families took the road north. Projects to settle and farm new land, the building of the Strand boarding school and laws designed to Norwegianise the area were all put into effect. The Norwegian authorities wanted to mark the fact that the west side of the Pasvik river was Norwegian territory. The Finnish language dominated in large parts of the valley. Many Norwegians in the valley learned Finnish in order to be understood by their neighbours! Living Finnish culture?In many ways, the Finnish culture survived the pressure from the Norwegian authorities. Many of those who today live in Pasvik are of Finnish origin. Names like Beddari, Sotkajærvi, Rauhala, Nikkinen, Kalliainen, Kurthi, Bordi, Randa and Ollila bear witness to Finnish roots. In the shops, you can hear people speaking Finnish; many older people keep the language alive. The children learn Finnish at school and learn about Finnish culture and traditions. The ties with Finland are still strong, 150 years after their forefathers took the road north.

|

|

When the border along the Pasvik river was established in 1826, it was the last piece of border to be laid down between Norway and another state. After the establishment of the border and the changes that brought with it for the original East Sami population, Finnish immigration to the area increased. The Norwegian authorities put into effect several initiatives designed to settle the area with Norwegians. Norwegian concernThe Norwegian authorities were concerned about the loyalty of the population along the newly established border, as the area was dominated by immigrants from Finland. Various initiatives were debated to increase the proportion of Norwegian population in the area, as well as the use of the Norwegian language. One strategy was to invite people from southern Norway and provide them with good conditions encouraging them to settle, cultivate the land and increase the use of the Norwegian language in the area. The objective was to spread Norwegian culture. At the same time, there was a wish to limit the spread of Finnish culture, through various laws. This succeeded to varying degrees. Why did people come from the south?In the years from about 1850 and up to World War I, many people emigrated from North Østerdalen. Most went to the USA, but many also went north. They settled where there was work, or where they could clear land for farming. Many communities had a surplus population and unemployment, and many were forced to move in order to find a new means of livelihood for themselves and their families. The people who went north to Sør-Varanger had a desire for better living conditions and wanted to start a new life. Many of those living in the Pasvik valley today are descendants of Norwegians who settled and started new farms in the border area.

|

The Norwegian government’s initiatives to influence population development in Sør-Varanger:1869: Roadbuilding28 roadbuilders were sent to Sør-Varanger in 1869, and another ten the year after. In 1872, ten roadbuilders and their families applied to have land surveyed to create new settlements. The roadbuilders continued their life in the area as settlers. The census and other sources show that the population of the Pasvik valley is increasing in number in this period, Finns and Norwegians are inter-marrying, and Finnish is the dominant language. 1899: AgricultureThis year saw the establishment of the Society for the Advancement of Agriculture in Finnmark. The Society’s aim was to advance agriculture in Finnmark, and to protect Norwegian interests. The methods used were free land and cheap loans to settlers. Advertisements seeking settlers were placed in newspapers in Trøndelag, Romsdalen and the northern parts of Gudbrandsdalen and Østerdalen. The project was not a success. It was not easy to recruit settlers from these areas, and for those who did go north it appears that the conditions failed to match their expectations. At the end of 1903, ten settlers arrived. In 1907 only three remained. The rest had left. 1903: Forest rangersForest rangers were employed in Pasvik, and state-owned forestry operations were started. The forest rangers’ job also included keeping the border under surveillance. Their tasks could include ensuring that no-one unlawfully used resources as grazing areas or hunted on the Norwegian side of the river − apart from people living in Norway. 1905: Boarding schoolsThe government set up boarding schools in the same year that Norway became independent. The first boarding schools were Fossheim in Neiden and Strand in Pasvik. At the boarding schools it was permitted to speak Norwegian only. The government wanted to see Norwegian become the dominant language. This was probably an effective barrier to the development of reading skills and learning in general. 1920s: New settlementFresh attempts were made to settle the Pasvik valley. This was part of a nationwide campaign to settle the area, and was justified by the need for increased self-sufficiency and to relieve the widespread unemployment. This time, too, the desire for a loyal Norwegian population in the border area was an argument for starting settlement initiatives in the Pasvik valley in particular. The Svanvik experimental farm was built up in the years 1934 to 1939. Svanvik was intended to focus on breeding of farm animals and plants, and to provide an educational and training institution for farmers.

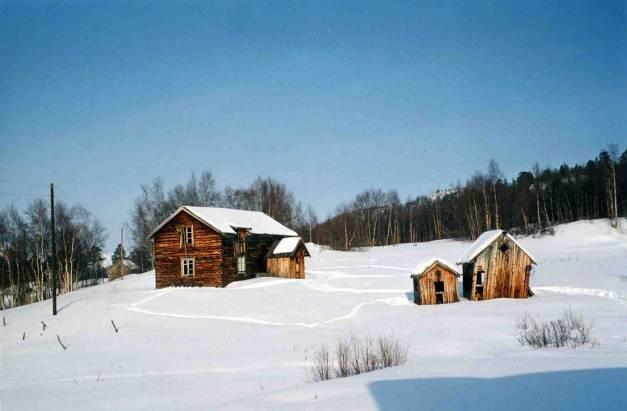

Bjørklund farm in winter. In 1869, Jon Pedersen Fætten came from Folldal to the Pasvik valley as a road-builder and cleared the land for Bjørklund farm. Bersvend took over the farm after his father and adopted the family name Johnsen. The farm’s last private owner was Bersvend’s eldest son, John Johnsen. Bjørklund was a working farm until the 1960s. (Photo: Sør-Varanger Museum)

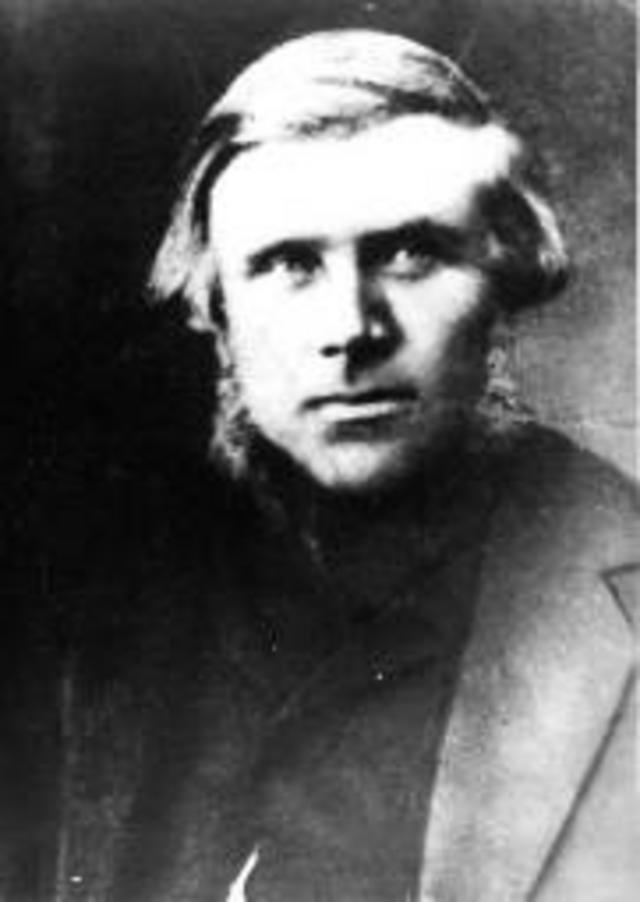

Ingebrigt Bersvendsen from Tynset. He came to Sør-Varanger in 1868. Bersvendsen bought the farm Namdalen from Pernille Tollefsdatter in 1871. His children were given the surname Ingebrigtsen, and there are many descendants of Ingebrigt and his wife Adrianna. (Photo given to Sør-Varanger Museum by Marianne Astrup))

Stabbur (storehouse) at Gammel-Eide at Svanvik. Several of the immigrants from southern Norway cleared land for farms in the Langfjord and Pasvik valleys. From Folldal came Lars Eide, who cleared land for Eide farm, and Ole Mellesmoen who cleared land for Mellesmoen farm, both near Bjørklund. Three neighbours from Folldal became neighbours in Pasvik. (Photo: Bodil K Dago, Sør-Varanger Museum)

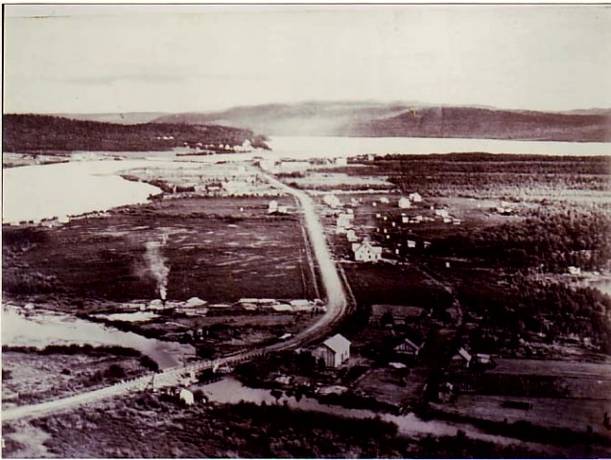

Mellesmo farm by the Pasvik river in 1907. Hard times in southern Norway and the possibility of work and a new life drove people northwards. Some found life in the far north too hard, while others settled in the Pasvik valley. Norwegian culture gained a foothold in the border country; today there are many descendants of those who settled here in the 1800s. (Photo: G. Soot. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Svanvik Chapel was consecrated on 5 September 1934. The chapel was built to provide a cultural and religious marking of the border. In the late 1920s, County Governor Lund stressed the importance of building a church on the Norwegian side. He had learned that Finland was planning to build a church in Salmijärvi, and was worried that the Finnish part of the population on the Norwegian side would use the Finnish church. (Photo: Sør-Varanger Museum)

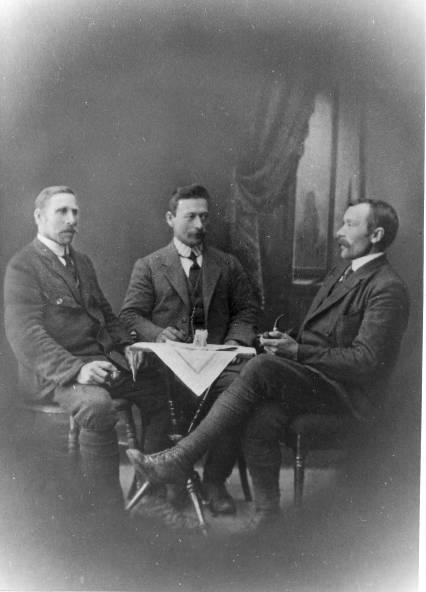

Forest rangers Anders Ryeng, Gudmund Gjetmundsen and Johan Hallen. The forest rangers also worked as inspectors along the border. Their job included preventing people from the other side of the river from using Norwegian land for grazing. In many ways, the forest rangers were the long arm of the state in the border area. (Photo: Helga Tokle. Lent by Guttorm Gjetmundsen. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The farm at Svanhovd was established in 1934 as the Norwegian state demonstration and experimental farm. Svanhovd played a key role in the effort to farm and settle new land in the Pasvik valley. From the mid-1980s, Svanhovd had fewer agricultural tasks and the farm was rented out. In the spring of 2005, the tenancy ended, animal husbandry ended and the land areas at Svanhovd are now rented out to other farmers in Pasvik. (Photo: Ragnar Våga Pedersen, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

Svanvik Lower Secondary School, built using government funds and which played an important role for education and Norwegianisation of the area. The first class of pupils at Svanvik were admitted in the autumn of 1936. The school was intended to give the west side of the Pasvik river “a fundamental tone that was completely Norwegian”. It would be a place where Norwegian customs and Norwegian interests could be brought together, and would provide tuition in theoretical and practical farming. The German occupying forces burned down the building in 1944 when they fled from the area. (Photo: Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Osvald Bordi and Johan Hildonen at work on building the Moslingveien road in 1935. The road was named after Sverre Mosling, who headed the effort to farm new land in the area. The building of a road all the way south to Grensefoss was part of the Norwegian authorities’ policy. The road was intended to improve communications in the valley, which would also tempt more settlers to establish in the border area towards Finland. Finland had built the Arctic Ocean Highway along the Pasvik river and right up to Liinahamari on the coast of the Petsamo area. (Photo lent by Wally Alexandersen. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections) |

|

In 1920, Finland became Norway’s neighbour also on the east side of the Pasvik valley. Finland wanted to mark its new territory and began building farms, shops, tourist stations and roads. Contact and trade increased between the peoples along the river. Finland gets PetsamoThe peace treaty between the Soviet Union and Finland was signed in Dorpat on 14 October 1920 and Russia was obliged to surrender the Petsamo area to Finland. This meant that the independent state of Finland gained access to the Arctic Ocean. Already over Christmas 1920, Finland began marking its new territory and soldiers were sent north. Finland established its own administration in the area and began building roads, schools, shops, churches, hotels and inns. Finland remained Norway’s neighbour east of the Pasvik river right up until 1944 when it had to surrender the area to the Soviet Union.

Good contacts across the riverThere were already many Finns living on the east side of the river when the area was Russian. But when the area became Finnish in 1920, many people went to live on the Finnish side of the river. Many on the Norwegian side had Finnish roots and had kept the language and the culture alive. There were good, close contacts between the people on each side of the river and they would often meet on festive occasions. Some found their sweethearts across the border. Stories are also told of football matches and other competitions between Norwegian and Finnish youth. Border tradeThere were frequent visits to the shops in Boris Gleb, Salmijärvi (Svanvannet) and Pitkäjärvi (Langvannet) in the inter-war years. Sugar, coffee and flour were cheaper there than in Norway, likewise tobacco and other goods. Not everything was imported lawfully into Norway, but the customsmen along the long Pasvik river had no possibility of checking all the traffic. For many, the Finnish shops were closer than the Norwegian shops.

|

Salminen family“On the other side of the river lived the Salminens.” Birger Erlandsen is one of many Pasvik valley dwellers who remember the contacts across the river. When Birger was a boy, it was Finland on the other side of the river. Until 1944. “We had a lot of contact with the Salminen family on the other side of the river. They were part of the family’s circle of acquaintance.” The Salminen family had a smallholding and also hunted and fished. “Some of the Salminen children have since visited us on the Norwegian side. Higher up from the Salminen place there was a shop and an inn. We used to shop there. For us it was cheaper and a shorter way to the shops. Of course, it wasn’t quite legal to go around the customs station, but that was a good bit further down the river,” says Birger, laughing. The risk posed by FinlandIn Finland during the years between the two world wars, ideas and plans were circulating in right-wing extremist environments, such as the Lappo Movement and the Academic Karelian Society, concerning the establishment of a Greater Finland. The objective of these organisations was to annex areas outside Finland where many Finns were living. Norwegian newspapers wrote frequently of the Finnish danger, and that Finland could pose a threat in the north. This created unease among the Norwegian authorities, but the Finnish authorities denied that Finland had plans to expand its territory. Norwegian marking of the areaNorway marked the fact that the area was Norwegian by building a chapel, a lower secondary school, a military garrison, roads, an experimental farm, and customs and tourist stations. They also initiated the third big settlement project in the Pasvik valley. The contacts between Finns on the Norwegian and Finnish sides were good. And there is nothing to indicate that the Finns on the Norwegian side of the Pasvik river wanted to become Finnish citizens. Their loyalty to Norway was without doubt great.

Finnish inn not far from Grensefoss. Finland built roads in the area and many from the Norwegian side travelled through Finland when journeying south because it was quicker than going on the Norwegian side. (Photo: Sverre Mosling. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Post box in the Pasvik river. There was plenty of activity on the river when Finland was our neighbour, with many boats ferrying people, cars and goods across and up and down the river. (Photo: Finnish Tourist Association. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

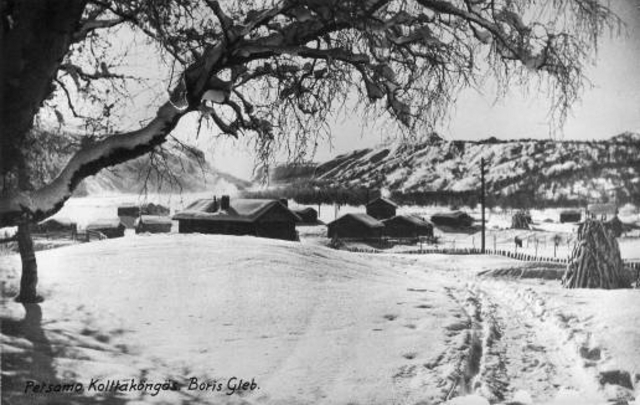

Boris Gleb in winter. A smugglers’ trail ran from Boris Gleb to Bjørnevatn. It was called “The Sugar Road” because a lot of people smuggled sugar from Finland. Nils A. Mortensen, who lived by Skafferhullet all his life, one hundred metres from the border, told how in the 1930s he and his sister used to follow the path. “There was a lot of smuggling, especially to Bjørnevatn. There were paths over the mountain. We found sweets in the snow along the path after people who’d lost them there. A lot of stuff was hidden, also cigarettes”, recounted Mortensen. (Photo: Järnvegsstyrelsen, Helsinki. Lent by Marja Fredriksson)

Pitkäjärvi, or Langvannet in Norwegian. Young people from the Finnish and Norwegian sides met to celebrate Midsummer Eve on the islet in the years between the wars. Contacts across the river between the neighbouring peoples came to a sudden end after the war. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen. Sør-Varanger Museum)

The opening of Svanvik tourist station on 12 July 1930. It was important for Norway to mark Norwegian land, and the authorities wanted increased Norwegian activity along the border. This was done by, for example, setting up this tourist station at Svanvik. (Photo: Works Director Torgersrud. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Memorial in Ivalo, Finland, commemorating those who lost their lives and their homes in the Petsamo area between 1920 and 1944. The Finnish-Russian War took place between 30 November 1939 and 13 March 1940. In the summer of 1941, Finland entered the Soviet Union together with the Germans. In September 1944, the cease-fire agreement was signed between Finland and the Soviet Union, and the Finns chased the Germans out of Finland. The Germans burned down nearly half the buildings in Lapland, and thousands were evacuated. Finland had to surrender the Petsamo area and parts of Karelia, among other areas, to the Soviet Union after the war. Thousands of people were unable to return to their homes. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Part of Salmijärvi before the war. (Lent by Olaug Skavhaug. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Finnish farms burning in Salmijärvi in December 1939. On 30 November 1939, war breaks out between Finland and the Soviet Union. Soviet forces invade the Petsamo area, and the Finns are forced to make a fighting retreat, burning most of the buildings, exploding bridges and destroying roads. Over 1,000 Finns leave their homes and flee to Norway, where they are well received and well taken care of. Finland gets back most of the Petsamo area as early as 13 March 1940, and the Finns begin moving back to their farms; or, to be precise, what is left of them. (Photo: Sverre Mosling. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Changes to the border east of the Pasvik river. The easternmost border line was Finland’s border with the Soviet Union from 1920-1940. The area east of the current border was also known as the Petsamo corridor. Finland was obliged to surrender the northernmost part of the Petsamo area to the Soviet Union in 1940 after the Finnish-Russian War. |

|

Germany invaded Norway on 9 April 1940. The German occupation lasted until May 1945. Sør-Varanger’s location meant that it was of great importance to Nazi Germany’s campaign against the Soviet Union. The German war machine became part of everyday life for the people of the border country. "Fortress Kirkenes"“Fortress Kirkenes” was the Germans’ most northerly entrenchment in Europe. Hitler’s plan was to attack the Soviet Union in both the north and the south. Sør-Varanger was to be the bridgehead in the attack against Murmansk. The ports of both Kirkenes and Murmansk are free of ice all year round; this was important for warships and supply ships. Military build-upThe first German soldiers came to East Finnmark in June-July 1940. During the autumn and winter huge forces and colossal amounts of arms and materials were transported to the border with Finland. The attack on the Soviet Union began on 22 June 1941 after a huge military build-up in Finnmark, particularly in the Kirkenes area. The German attack on the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 made Norway an important strategic point in the war between the great powers. Finnmark and Finland became military deployment areas on the northern front.

German ships in the fjord“I remember when German ships sailed into Bøkfjorden for the first time. It was in June 1940. We were salmon fishing at sea. The Germans had a band on deck playing military marches. It resounded all round the fjord. My grandfather said: «Hope they get out again fast»,” recounted Ingvald Henriksen, who was 13 years old in 1940. Over a thousand air raidsThe Germans completely dominated the lives of the local population of this north-eastern area, both in their workplaces and in their homes. The fact that Fortress Kirkenes was of course an important target for the Soviet Russian allies did not make the situation easier. Over a thousand air raids during the war years say it all. Kirkenes was bombed to destruction.

Contact with the soldiersThe war left deep traces among the population of the Pasvik valley and Sør-Varanger. In many ways, the rural communities came out of it better than Kirkenes, and most buildings in the countryside were still standing after the war. Many people who were children during the war tell of their good contact with the soldiers. “They were only young boys sent to the north. Most of them behaved well,” say many in the Pasvik valley. “They would sometimes give us sweets or a bit of food.”

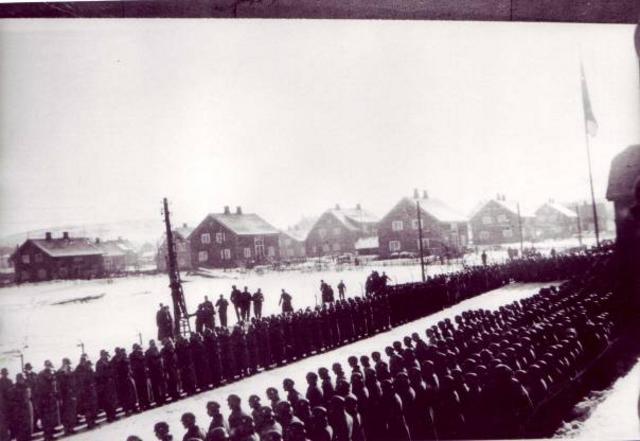

German troops lined up in Storgata, Kirkenes, 1942. “Fortress Kirkenes” was by then well established. Kirkenes was strategically important for Nazi Germany in its attempt to take Murmansk. Naturally, this made Kirkenes a target for the Soviet Union’s bomber planes. Air-raid shelters were a part of everyday life for the population during the Nazi occupation. (Photo: Edvardsen. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

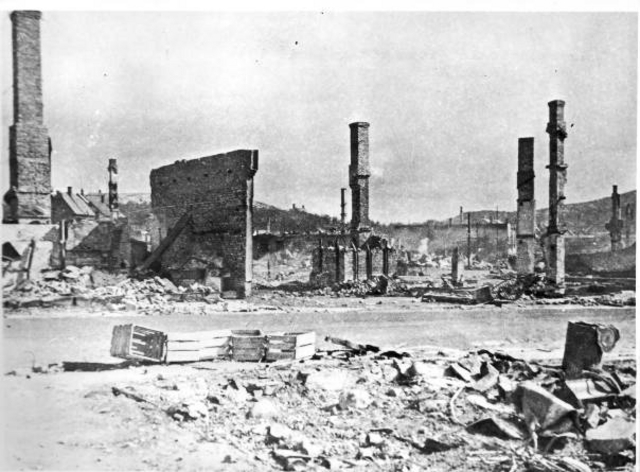

Kirkenes after the bombing on 4 July 1944. The town lay in ruins. Homes were gone. Only a few houses remained standing. For many, the post-war period was very hard; it took a long time before supplies came to Sør-Varanger. (Photo: Unknown. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

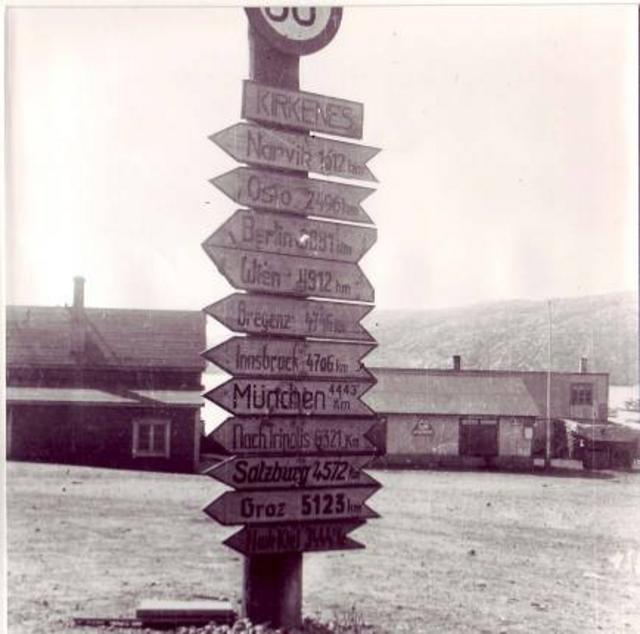

Signpost at Lønbom square in Kirkenes, 1943, featuring the names of many Austrian towns. Many Nazi soldiers were from Austria and were used to harsh winter conditions. But the Russian winter on the Litsa front proved too tough for thousands of soldiers. (Photo: German pilot. Lent by Hiltrud Vozz. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

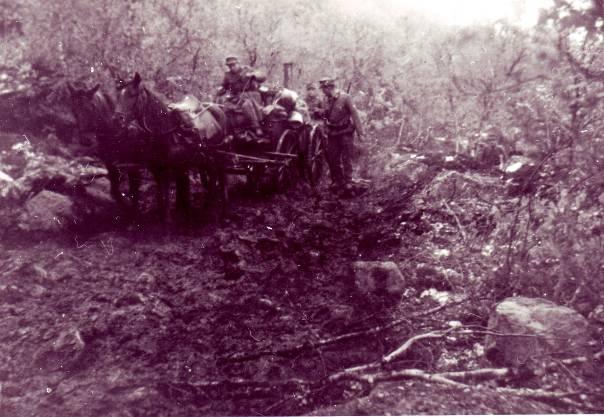

The Litsa front in the summer of 1941. German field kitchen being brought to the positions. Thousands of Russian and German soldiers died on the Litsa front. The casualty figures have varied greatly and are still uncertain, but the German casualties on the Litsa front probably reached 35,000 men, including wounded. Russian historians estimate that the Red Army had as many as 73,000 dead and 129,000 wounded, 202,000 casualties in total. (Photo: Unknown. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The German bridge at Hestefoss on the Pasvik river was destroyed by explosives in 1944. The Germans employed scorched earth tactics when they left the area. Fortunately, not many privately owned buildings in the Pasvik valley were burned. (Photo: Petra Johnsen. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Russian soldiers at Boris Gleb. (Photo: The Red Army. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

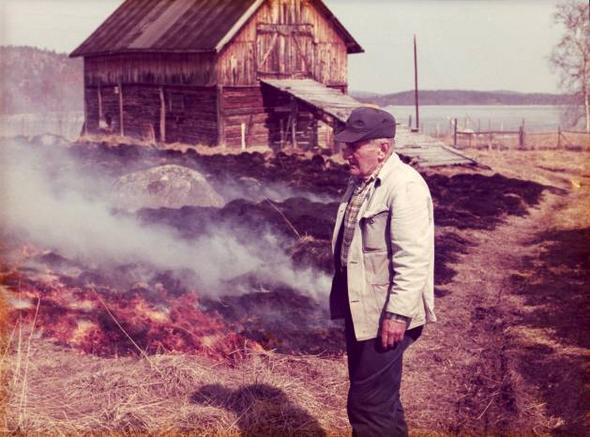

“The Russians swam over the Pasvik river at Trangsund,” says Åse Andersen. Åse’s father, Olav Kærnæ, told how they took materials from the cowshed and built rafts to get the soldiers across quicker. The Germans were on the farm, but one of the girls on the farm told them that the Russians were on their way. That made the Germans get a move on; they ran with their shoes in their hands! In the picture we see Olav Kærnæ on the farm at Trangsund in 1980 with the Pasvik river in the background. (Photo lent by Åse Andersen)

The liberation in 1944. Sør-Varanger was the first area in Norway to be liberated, on 24 October 1944. The Germans were in a tremendous hurry to leave, and had insufficient time to evacuate the entire population. Over 2,000 people lived in the mine tunnels in Bjørnevatn; ten children were born in A/S Sydvaranger’s tunnel. (Photo: The Red Army. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The last Russian divisions leave Sør-Varanger and Norway on 25 September 1945. Some feared that they would stay. The people of Sør-Varanger will always remember that the Red Army liberated them from the German occupation. (Photo: Karlsen. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections) |

Prison campsThe Germans took many Russian soldiers prisoner during the fighting. Several prison camps were built in Sør-Varanger, with a total of 14 camps in Pasvik. The prisoners were treated virtually like animals. Very many Russian prisoners lost their lives due to malnutrition or exhaustion, or they were simply executed. The sight of the emaciated prisoners made an indelible impression on the local population. Many managed to smuggle a piece of bread or other food to the Russian prisoners. Sometimes the prisoners gave the locals carved wooden figures, tin boxes or other handmade objects in gratitude for their help. PartisansMany individuals enrolled in the service of the Soviet Union during the war in order to fight the Nazis. They received training in the Soviet Union before being sent back to Norway to report to the Soviets. These people were called partisans. One of the most well-known is probably Osvald Harjo from Pasvik, who spent more than ten years in Soviet prison camps. He did not return to Norway until Prime Minister Gerhardsen took up his case in a meeting in Moscow. The partisans lived a dangerous life, as they could be discovered by the Germans at any time. Or they could be informed on. If they were caught, execution and death awaited them. Many partisans ended their lives in the border area. The Arctic Ocean front against MurmanskThere was little in the soldiers’ exhausting journey across marshes and rivers that resembled the dreams their generals had had about marching gloriously into Murmansk. There were long distances over a roadless, sometimes ice-cold and barren landscape. Stones, mountains and precipices, deep mud, swift rapids and Russian soldiers offering stubborn resistance barred the way to Murmansk. The frost came and the cold crept through clothing and into the bones. The thrust against the Soviet Union stranded in the Litsa valley, not far from Murmansk. The Germans had underestimated both the terrain and the Russian resistance. The Russians made better use of the terrain than the invaders, and many Russians had experience from the Finnish-Russian war. The Russian winterBoth the Germans and Russians got lost in one fateful storm at Litsa and many perished from cold and exhaustion. Their forces were halved because of snow blindness and frostbite. The fight caused incomprehensible suffering.

From «Krig i Grenseland» (“War in the Border Country”) by Hans-Kristian Eriksen LiberationThe Germans never reached Murmansk. In the autumn of 1944, the Soviet forces managed to press the German troops westwards. In October that same year the first Soviet soldiers crossed the border into Norway. Sør-Varanger was liberated as the first area in Norway.

|

|

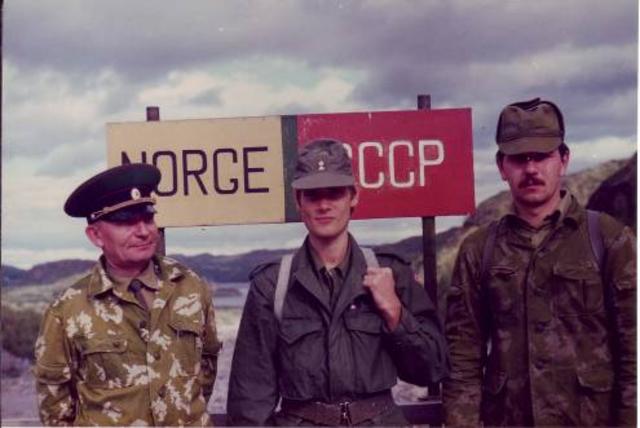

After World War II, the world was divided into two power blocks, the Soviet Union and the USA. This was a time of suspicion and both blocks were on guard. The border was under constant surveillance and anyone who had Communist sympathies and any contact with the Soviet Union was monitored. However, despite the Cold War, there were examples of contact between the countries, including a variety of cultural exchanges. The Cold WarThe Cold War is the name given to the period from after World War II and until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The period was characterised by the rivalry between two groups of nations that practised different ideologies and political systems. On the one side was the Soviet Union and its allies (the Eastern Block), and on the other the USA and its allies (the Western Block). The situation was referred to as the Cold War because it never led to any direct fighting or war. New neighbour in the eastAfter the armistice of 19 September 1944, Finland had to give back the Petsamo area to the Soviet Union and Norway acquired a new neighbour in the east. This meant many changes for the people of the area. The Pasvik river, which had hitherto been a connecting link between neighbours, now became a barrier between them. On the Soviet side, a border fence and many observation towers were set up to register all movements on the Norwegian side. It was forbidden to cross the river and any non-compliance resulted in stiff fines. Under the Order in Council of 1950, it is not permitted to cross the border line on land, in the water or in the air. Nor is it permitted to speak to or to have any other kind of contact or dealings with persons on the other side of the border.

My fishing spot!The story is told of an elderly fellow living on the Norwegian side of the border at Melkefoss. He had been neighbours with both Russia and Finland, and had always fished in the same spot without any problems. When the Soviet Union became his neighbour after World War II, he continued fishing where he had always fished. His fishing spot was on the other side of the Norwegian-Soviet border, but he did not care which country and which laws applied. He was determined to fish, and continued as though nothing had happened. In the end, the story goes, the border guards got fed up of reprimanding him; so he simply carried on fishing in «his» spot in the Soviet Union. |

DefenceAfter the Red Army left East Finnmark in September 1945, the border was guarded by divisions from the Norwegian Army and the Police. The Sør-Varanger Garrison (GSV) was given its current name in 1947, and it was decided to build up the garrison again at the Høybuktmoen airfield that had been built by the Germans during the war. When Norway became a member of NATO in 1949, the Norwegian-Soviet border also became a border between NATO and the Warsaw Pact countries. This led to a further stepping up of surveillance on both sides of the border, and the ensuing period was dominated by mutual suspicion between the two countries. IntelligenceThe intelligence service in Sør-Varanger was expanded after the war and Sør-Varanger Police Headquarters became one of Norway’s largest in terms of numbers of employees as the Police Surveillance Service (POT) was based there. Communism was strong in Sør-Varanger after the war and as a result many people were put under surveillance as possible agents in the service of the Soviets. At the same time, it was important to have an overview and knowledge of the Soviet forces in order to be prepared if they should ever attack Norway. The Cuba missile crisisThe most serious confrontation between the two super-powers of the USA and the Soviet Union arose between 15 and 28 October 1962, when a U2 plane on a routine mission discovered that the Soviet Union had missiles stationed on Cuba that were aimed at the USA. For 13 days, the entire world held its breath while negotiations went on between the USA’s President John F. Kennedy and the Soviet Union’s Nikita Khruschchev. Soldiers at the Sør-Varanger Garrison were called out with weapons loaded with live ammunition. 1968 - Soviet demonstration of strengthEarly in June 1968, the Norwegian border stations observed increasing activity on the Soviet side. Several columns of vehicles were driving eastwards on the Russian Highway and, on the evening of 6 June, tanks, track-driven vehicles and artillery were observed on the Arctic Ocean Highway and moving northwards towards Boris Gleb. Because of bad weather it was difficult to estimate the scope of the advance and the size of the forces involved. On the morning of 7 June it was clear that large Soviet forces had grouped and taken up positions right behind the border line.

Alarm! Alarm!On the night of 7 June 1968, the alarm went and soldiers from the Sør-Varanger Garrison set out for the border line and prepared to fight. The Soviet divisions dug themselves down and aimed all their weapons at the Norwegian positions, observation posts and border stations. It was clear to all that this was not a routine exercise. Not since World War II had there been such large Soviet army divisions so near to the border. The Soviet forces remained in the border area until 12 June.

A border sub-commission during the staking out of the frontier between Norway and the Soviet Union in 1947. From left: Mrs Gerda Strand, interpreter. H. Jelstrup, astronomer. Captain Machauko, secretary. H. Sadierew, interpreter. Head of department S. Mosling, chairman. A. Modt, book-keeper. Lt-Col. Stretkow, chairman. Lt-Col. Tilitryn. Lt-Col. Frantzuk. (Photo: Unknown. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

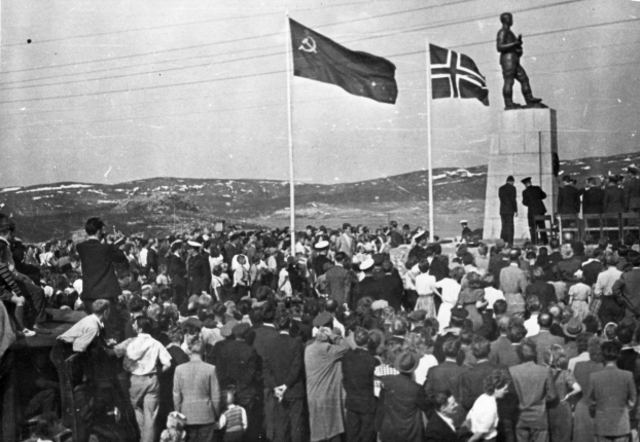

Unveiling of the memorial commemorating the Russian liberation, 8 June 1952. (Photo: Unknown. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

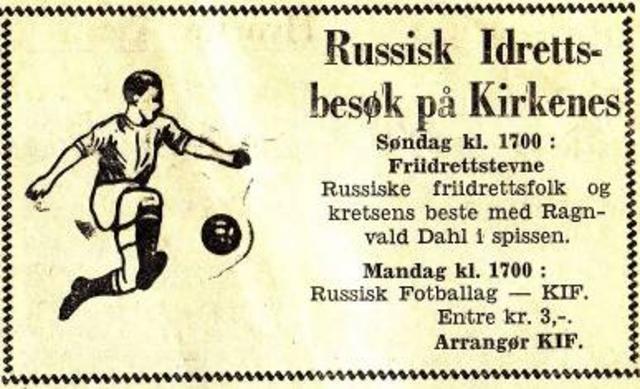

Even though the border between Norway and the Soviet Union was closed to public traffic during the Cold War, there are several examples of exchanges between the two countries; in connection with the hydropower development of the Pasvik river, many Norwegians worked on the installations in the Soviet Union and we have a number of exchanges in connection with sport and culture. Marching bands, choirs, football and wrestling are examples of cultural exchanges conducted during the Cold War. (Newspaper advertisement in Sør-Varanger Avis, 25 July 1959)

In 1965, when building work at Skoltefoss was finished, the Soviet authorities decided to give people the opportunity to visit Boris Gleb without a visa. There was a hotel and a bar there, as well as a shop where cheap cigarettes and vodka could be purchased. It would be a year-long trial project, and proved to be a highly popular destination for Norwegians. However, the Norwegian government said no to extending the arrangement, as they feared it would make it too easy for agents in the service of the Soviet Union to come into contact with their principals. In addition, there was a great risk of people being recruited as spies.

Although the border is closed, reindeer often wander over onto the Russian side. Here we see Norwegian reindeer owners on the Soviet Union side who have come to look for reindeer that have strayed over the border. (Photo: Border Commission)

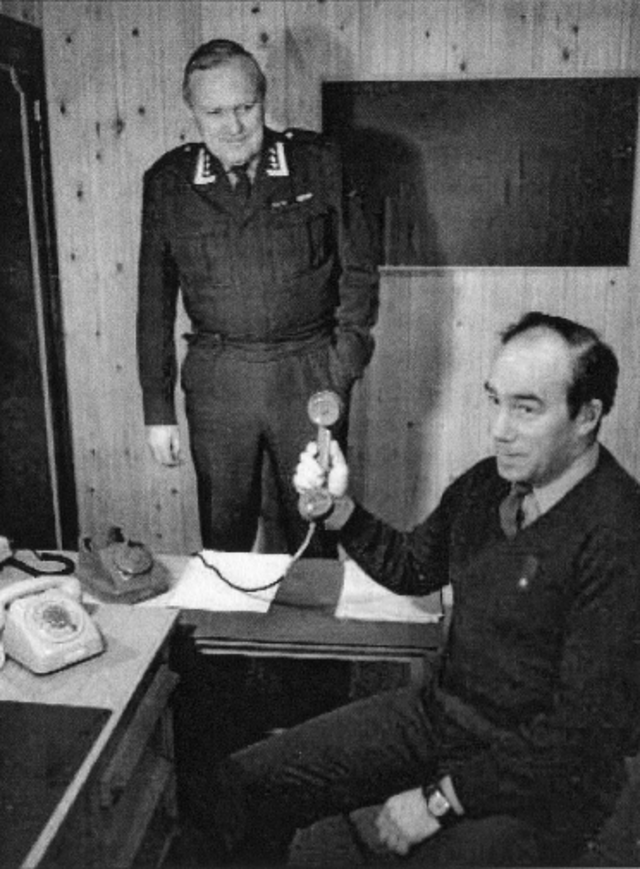

The biggest challenge to the co-operation between the two countries was communication. However, after the then Norwegian Prime Minister, Einar Gerhardsen, raised the issue during an official visit to Moscow, a telephone line was set up between the parties. The red telephone was used for two hours every weekday and one hour on Saturdays. Here, Colonel Tore Hiort Oppegaard and Captain Knut Tharaldsen proudly display the red telephone. (Photo: Unknown)

Major Golovin, Lieutenant Berstad and Lieutenant Kazakov at the Boris Gleb dam. From a border inspection visit. (Photo: Border Commission)

Norwegian and Russian soldiers saw down border marker 407 on the Russian side. The co-operation with the Soviet Union includes an annual staking out of the frontier and this time a marker has to be moved. (Photo: Border Commission)

International wrestling competition in Murmansk in the 1980s. Norwegian and Soviet athletes frequently met to compete in both Norway and the Soviet Union. Although relations between East and West could be cool during the Cold War, it did not cause contacts to be broken between Norway and the Soviet Union. The attitude of the local population to the Soviet Union was somewhat different than in the rest of Norway. For many, it was natural to maintain contact with the Soviet people. (Photo: Kjell Erik Andreassen) |

|

Mikhail Gorbatchev, President of the Soviet Union from 1988 to 1991, initiated a campaign for greater openness, or "glasnost" as it was known. As a result, political and historical issues that had previously been taboo were now the subject of public debate. Under the collective term "perestroika", political and economic reforms were put into effect. This was the beginning of the end of the power monopoly that had ruled and the start of the development of democratic government in the USSR, later Russia. More open bordersAfter Russia was declared a new, independent state in 1991, the border was opened for traffic. It became easier to travel to Russia and there was an increase in the number of people crossing the border both ways. However, the biggest change was the increase that took place in cross-border co-operation, not least in business and culture. A number of Norwegian companies became established in Russia, and in the building and construction sector in particular there was a lot of investment in the east. Major building projects in Murmansk, Zapoljarnij and Nikel were given to Norwegian firms. Increased tradeIn recent years there has been a huge increase in cross-border trade. Not only has there been very substantial co-operation in business development, but we are now seeing a big increase in trade in the private sector. There is a large and varied selection of shops in Kirkenes, and the growth in Russian purchasing power has also tempted many Russians to make their shopping trips to the town. That Russian customers form part of the target group for Kirkenes’ shops is evidenced by the fact that many now label their goods in Russian. But trade goes the other way, too. It has become customary to take shopping trips to Nikel, Zapoljarnij and Murmansk. A number of firms hold their Christmas parties over the border in Russia and people often take weekend trips to Murmansk to shop.

The Kirkenes DeclarationOn 11 January 1993, a conference was held in Kirkenes on the theme of co-operation in The Euro-Arctic Barents Region. Present at the conference were representatives from all the Nordic countries and The Russian Federation. Extended co-operation within The Euro-Arctic Barents Region would create stability and prosperity in the area, and teamwork would now replace previous confrontation and division. The co-operation was also intended to contribute to international peace and security. In the wake of the declaration, the Barents Secretariat was set up and the Barents Region was established as a concept. |

Little MurmanskKirkenes has been called Little Murmansk because of its rapprochement and co-operation with Russia. The main streets of the town have street signs in both Norwegian and Russian. There are always Russian trawlers in at the quayside to take provisions on board and to repair their boats. It has become common to hear Russian spoken in the streets of Kirkenes and a large number of the municipality’s inhabitants come from Russia. Today, approximately 600 of the municipality’s 9,500 inhabitants are Russian. Russian marketA highly popular initiative under the auspices of the Barents Region Co-operation is the Russian market. On the last Thursday of every month, Russian stall-holders come to Kirkenes to sell their goods. Most things can be bought here, including Russian crystal, wooden articles, jewellery and clothing, as well as a large selection of other goods. ShippingKirkenes has approximately 750 calls from Russian ships during the course of a year. On average, there are 25 trawlers in port every day. Port activities account for a turnover of around NOK 1 billion. Several companies specialise in shipping, providing ships’ supplies, legal assistance, paying wages to ships’ crews and organising any ships’ repairs needed.

Road sign outside Kirkenes. (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

The main street in Kirkenes in Norwegian and Russian. (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

The Barents Ski Race 2005, a collaborative project between Norway, Russia and Finland. The ski race goes over 12 km, through all three countries. The event is extremely popular and celebrated its 10th anniversary this year. It attracted about 1,000 participants from all three countries in total and was a real people’s party! (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

A broad selection of Russian nesting dolls. (Photo: Ingar Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

View from “Hill 96”, an old military observation tower in the Pasvik valley. In the foreground we see Norway and the Pasvik river. The border passes through the middle of the river and on the other side can be seen the Russian town of Nikel. (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Border street at Holmfoss. (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Border inspection groups, 1993. Back, from left: Captain Ekerhovd, Major Balasjov, Captain Tollånes, Captain Vousnjouk, Lieutenant Lassemo, Captain Sjalapin, Captain Petrukhin and Lieutenant Bøhler. Front, from left: Second Lieutenant Bogen, Lieutenant Vesjlevtsev, Major Lobasjuk and Captain Berg (Photo: Border Commission)

The Spareland shopping centre bears witness to the fact that Russian purchasing power is important for Kirkenes. (Photo: Hanne Bones Vangberg, Sør-Varanger Museum)

The "Russian market" in Kirkenes attracts a lot of people. Crystal is popular. And keep in mind that it’s always possible to haggle, with a twinkle in your eye! (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum) |