The Pasvik River

One river - three states

Down through the centuries, the people of the Pasvik valley have harvested the resources of the Pasvik river and surrounding area. The area has been a meeting place for different peoples: Sami, Finns, Russians and Norwegians. Different cultures have met and developed through time. People have learned from one another and benefited from one another’s experience. Many traditions have been maintained and continued in modern society.

|

|

|

The Pasvik river is rich in fish, and fish have always been important for the people along the river. Whitefish and pike have been an important part of the diet. Net fishing, in summer and winter alike, meant a great deal for all the peoples living in the Pasvik valley. The Pasvik river salmon were already famous in the 1800s, when the first English salmon fishermen made their way north. Salmon weighing over 20 kg were quite common at the Skoltefoss falls. Many enjoy angling today, and you may be lucky enough to land a 10-kg trout or an even bigger pike. Fish as foodMost of the species of fish in the Pasvik river make good eating. Whitefish, pike and perch have been served up on many a dinner table. Some prefer burbot, which is a kind of cod. Salted burbot roe are quite a delicacy. However, perhaps the most popular fish today is the king of the Pasvik river, the trout; although, if one talks to some of the older generation, pike and whitefish are highly regarded. Pike is a useful fish and can be fried as fillets or used to make delicious pike fishcakes. Perch tastes best as crispy fried fillets, or preferably deep-fried. Perhaps the most important edible fish through the centuries has been the whitefish, which can be used for most kinds of cooking. Poached, lightly salted whitefish is extremely good. Fried or grilled, whitefish is delicious. Cured or salted whitefish is said to be better than both trout and salmon. Should you wish to try the delights of whitefish, cured whitefish can be a good place to start. You will need the following:

Gut and clean the fish and fillet it, but leave the skin on. Scrape off the scales. Place a small handful of rock salt in the bottom of a bowl (and a tiny amount of sugar). Lay the fillet in the bowl with the skin side down. Sprinkle half a handful of salt over it, and a little sugar. Leave the fish to stand for a little less than 24 hours. Rinse the fish, and leave it to rest and dry a little. Cut thin slices of the fish and lay it on brown bread. Top with raw onion slices, slices of whole red pepper and a little sprig of dill. Bon appétit! PerchPerch is one of the dominant species of fish in the lakes in Pasvik, and perch can be caught weighing up to 1.5 kg! Perch is a predator that eats everything from bottom-dwelling organisms to fish, even other fish of its own species. The food chain of a predator like perch can be complex, and in Vaggatem a perch was caught which had eaten a pike, which in turn had eaten a perch! Hydropower and fishThe regulation of the Pasvik river for hydro-electric power has destroyed several of the spawning and breeding grounds for trout, which has led to a sharp decline in stocks. To compensate for these negative effects, the power company Pasvik Kraft sets out 5,000 trout in the river every year. In a test fishery done by the Norwegian College of Fisheries Science, the bred trout that were set out in the river accounted for over 80% of trout catches in the lower part of the Pasvik river. The proportion of wild fish was a little higher in the upper part of the river system, which may indicate that the spawning conditions are better there. The most important edible fishWhitefish has always been the most important edible fish for the people of Pasvik, but most of them are probably unaware that there are two different kinds of whitefish in the river system. Plankton whitefish live out in the open waters and seldom grow larger than 100 g. Lake whitefish, on the other hand, can grow up to 4 kg. Lake whitefish live in the strand zone, where they feed on bottom-dwelling animals such as insect larvae, snails and molluscs. |

Fishing with Aage Beddari.

The Pasvik river is known for its large trout, with trout weighing up to 10 kg being caught in the river. Surveys by the Norwegian College of Fisheries Science have shown that both wild trout and bred trout that have been set out in the river grow at an enormous rate. In June 2004, 1,000 of the bred trout that had been set out in the river were marked with a number, and when they were re-caught in September 2005 some had grown by up to 1.6 kg! In the picture we see Karl Øystein Gjelland from the Norwegian College of Fisheries Science. (Photo: Ingrid Jensvoll, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

Pike are the biggest predatory fish in Pasvik, and it is not unusual to find pike weighing up to 14 kg. They live in the strand zone of lakes where they chiefly eat other fish, although pike are omnivorous and in their stomachs have been found everything from muskrats to ducklings. In the photograph we see Erling Beddari. (Photo: Per-Arne Amundsen, Norwegian College of Fisheries Science)

Vendace is a new species in the Pasvik river system. In only a few years it has become a dominant species which has had a great impact on plankton whitefish and trout, among others, in the watercourse. Vendace make attractive food for trout, and 63 vendace have been found in the stomach of a 5 kg trout! Vendace also compete hard for food with plankton whitefish. The two species look similar and can be confused, but are distinguishable inasmuch as vendace have an underhung jaw. (Photo: Karl Øystein Gjelland, Norwegian College of Fisheries Science)

Nets and fish traps have been used and are still used for catching fish in the river. River fishing is still important for local people, with many upholding the tradition of harvesting the river’s riches for food. Cured whitefish, pike fishcakes and crispy fried perch are delicacies on many a table. (Photo: Anne Mette Bjørgan, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Einar and Helge Strømme with a good catch of salmon at Elvenes on 3 August 1946, not far from the mouth of the Pasvik river. Pasvik salmon were famed for their high average size; they were broader and shorter than salmon in other watercourses. Salmon apparently went all the way to Harefoss before the development of the lower part of the river started at the end of the 1950s. (Photo lent by Helge Strømme)

Fishing for burbot on the Pasvik river. Students from Svanvik Folk High School try their luck fishing on a dark, cold winter’s night. Many people regard burbot as a delicacy. (Photo: Jonas Endre Karlsbakk, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Ice fishing competition at Loken by the Pasvik river. A popular activity when the sun begins to warm the land again. (Photo: Anne Mette Bjørgan, Sør-Varanger Avis)

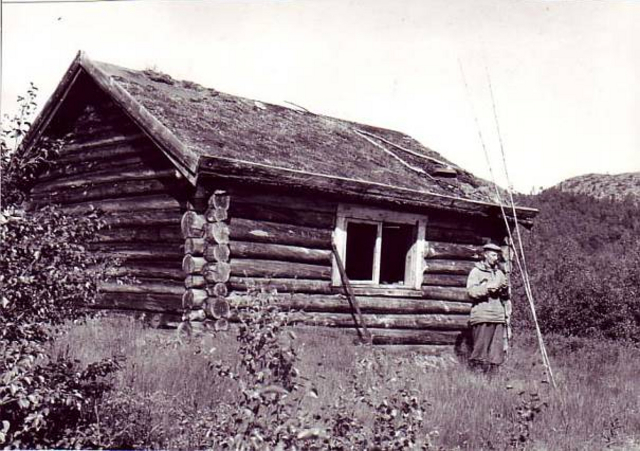

Fishing hut at Holmfoss in the 1930s. The Pasvik river’s falls and rapids were known for being rich in big trout and many anglers have found their way to the river. As early as the late 1800s, English fishermen came here to catch big salmon in the lower parts of the river. (Photo: Rolf Celius. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Seines on the Inari lake. Fishing has always been important for the people living by this large lake. Before the lake was regulated in connection with the hydropower development, the annual catch was estimated at 250,000 kg. Now the annual catch is about 150,000 kg. The biggest trout caught here weighed 15.1 kg. (Photo: Hanna Ylitalo, Metsähallitus) |

|

The use of reindeer and reindeer herding have long traditions in the Pasvik valley. The reindeer was important as a means of transport for all the peoples of Pasvik. The custom of keeping farm reindeer was maintained well into the 20th century. Many farms had only a few animals. Today, there are larger units with more animals, although many families are still involved in reindeer herding. Reindeer Husbandry ActIn 1978, Norway passed the Reindeer Husbandry Act, which regulates present-day reindeer herding by Sami in Norway. Reindeer herding is divided into districts. Pasvik has one district for reindeer herding, district 5A/5C. The reindeer owners are divided into operational units. Today, there are five operational units in Pasvik. Operational unitsEach operational unit comprises a number of individuals within one family who are involved in reindeer herding. In the rest of Sør-Varanger there are a further two districts, in Jarfjord and Neiden/Bugøyfjord. A good number of the reindeer owners in Pasvik are members of the Sami Reindeer Herders’ Association of Norway, which is a trade union for reindeer herders.

EconomicsOnly a few people can make a living exclusively from reindeer herding, as a rule only the owner of an operational unit. Although in Norway today there is a greater percentage of men who are operational unit owners, a large number of women are active in day-to-day reindeer herding. As in the rest of the country, most young people are forced out into jobs outside reindeer herding, for economic reasons. TechnologyApart from snow scooters, reindeer owners today are also dependent on other modern equipment to carry out reindeer herding. One must always have a lasso handy, and it is important that it should be appropriate to the season and the requirements. A skilled lasso-thrower is highly respected in herding environments. A pair of field glasses and a knife, are other tools one cannot do without. Some reindeer herders have tested GPS, which can be a useful navigational tool. GrazingThere is relatively good grazing land in the Pasvik valley compared with other places in Finnmark. Herding goes extremely well here, there are plenty of new calves and plenty of reindeer go to slaughter, despite the presence of predators like wolverines, wolves, eagles and even some bears. The reindeer are good and beefy, as can be read from the total accounts for all reindeer herding kept by the reindeer herding administration in Norway.

|

Over the borderReindeer sometimes stray across the frozen river in winter. When that happens, the reindeer owners have the possibility of bringing them back. The members of the reindeer grazing district have an agreement with the Border Commission, which permits them, when necessary and by agreement, to drive over the border on snow scooters to fetch the animals back. This arrangement was also in operation during the Cold War. The reindeer herders in the Pasvik valley have upheld the craft traditions associated with reindeer herding. There has been continuity in the transfer of knowledge between the generations. Even today, the characteristic Sami moccasins and homespun lokka are still made and decorative bands are woven. The people use local patterns from Sør-Varanger, and the close ties with the Inari region of Finland are much in evidence in the patterns. EducationSome of the young people from the Pasvik reindeer grazing district have completed courses related to the herding industry at upper secondary school level. There is more and more paperwork and bureaucracy associated with reindeer herding. The training these youngsters receive will help herders keep up-to-date with modern demands in their day-to-day operations.

Gunnar Olsen using a scythe for haymaking. In the summer months herding is more sporadic and time is spent on other types of activity such as repairing fences and other structures. In the summer there is mowing, to bring in the hay for winter feed. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Stian Beddari in the reindeer woods. During the winter months the reindeer herders drive out daily to their herds to tend them. The herds are spread in small groups in upper Pasvik. The reindeer are periodically given scouring rush and dried hay as extra feed. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Winter feeding. Periodically feeding the reindeer with dried hay in the winter makes the herd more tame. Feeding also prevents hunger emergencies in that the reindeer’s digestive system is accustomed to hay and the herd are used to being fed. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Nadja, a West Siberian Laika. Herding dogs are the reindeer herders’ good friends, working partners, and useful tools in the day-to-day work. The most commonly used dogs are various crossbreeds with combinations of important characteristics. A good example is a Lapphund combined with other breeds. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Reindeer gathering in Biekana. In the autumn, the animals are herded together into a large pen so that they can be marked and selected for slaughter. Locally, these reindeer gatherings are called bugælus, and have traditionally been events attracting large numbers of local people from the Pasvik valley. Reindeer destined for slaughter are sold to wholesale buyers, and collected in animal transport trucks. The reindeer owners also select reindeer to use for their own food supply. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Anja Beddari prepares the tackle for reindeer sleigh driving. Some reindeer owners tame reindeer to use for pulling sleighs. Picking out the most suitable animals is an art. It takes a long time to train reindeer for this purpose, and it demands patience and knowledge of the animal. The art of taming reindeer is passed down from generation to generation. Driving reindeer are important for the herd and for the herders. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Hans Kalliainen cutting rush. In September the reindeer owners cut horsetail or scouring rush. This is a type of rush that grows in the Pasvik river and that makes excellent reindeer feed. The owners gather to cut the rush in a collective effort on behalf of all the members of the reindeer grazing district. The rush is dried in the autumn and used in winter. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Selecting reindeer. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Reindeer gathering. (Photo: Mette Hallen) |

|

There is a long tradition of agriculture in the Pasvik valley. In the 1800s, Finns and Norwegians settled in the fertile valley. Outlying land was cleared, and farming was and still is an important industry for many people in the valley. New settlementsIn the mid-1800s, many Finns and Norwegians moved to the area. Most established themselves with farms, combined with other livelihoods such as small-scale fishing, gathering and reindeer herding. Migration to the area continued, many children were born, and in 1900 there were over 200 people living along the river and in the Langfjord valley. However, some people gave up the attempt to settle the land and left the valley. Modern agricultureToday, there are many farms along the length of the Pasvik valley. The farms of today are large, modern and varied. Farmers keep cattle, pigs, horses and also cultivate the land. Potatoes, carrots and a wide selection of other vegetables are also grown. There are several nurseries, and some people cultivate herbs and have small-scale production of spices. |

Old, horse-drawn mowing machine used by the Erlandsen family on the Krokvik farm. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

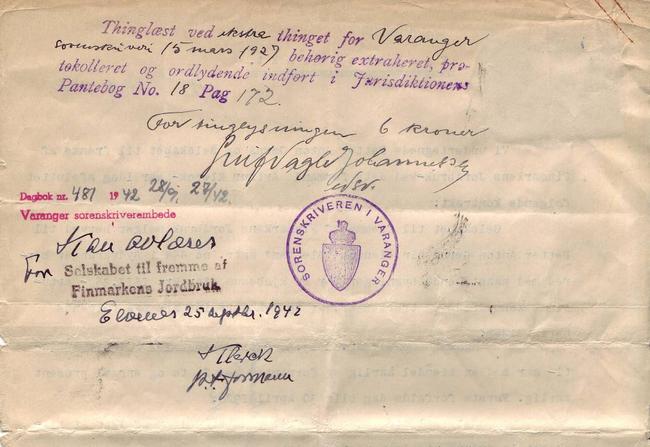

Documents from Sletten farm. The farm was bought by the Society for the Advancement of Agriculture in Finnmark. The farm is now owned by John Andersen.

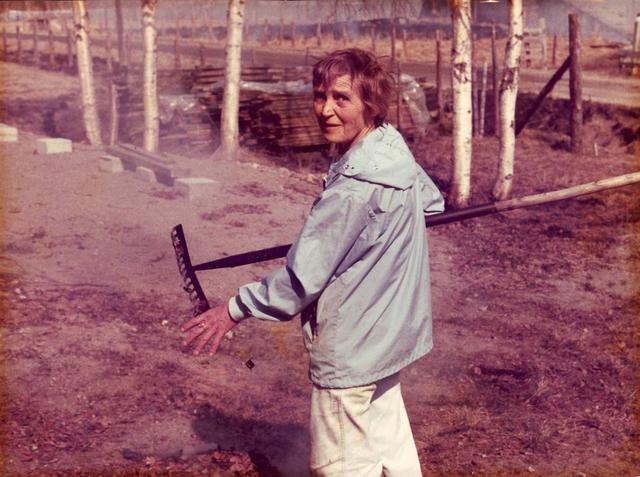

Burning garden debris. Ragna Kærnæ in 1980. The farm has been owned by the family for over 80 years. (Photo lent by Åse Andersen)

Apple-growing so far north? Svanhovd Environmental Centre does all kinds of research into plants, animal life and the environment. (Photo: Tor Sandø, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Svanvikstua. Built by Hans Kirkgaard who came from the south. Kirkgaard experimented with growing different types of grain; not all types of grain tolerated the northern climate. Kirkgaard became the township’s first mayor. Svanvikstua is now part of the Sør-Varanger Museum. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Haybarn at the Kalliainen farm at Strand. The Finns who came to Norway were skilled farmers. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Harvesting timothy at the Experimental Farm at Svanvik. (Photo: Anne Mette Bjørgan, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Cosy moment in the cowshed. (Photo: Anne Mette Bjørgan, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Cat and pig on Kristian Beddari’s farm at the end of the 1960s. (Photo: B. Bugge. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections) |

|

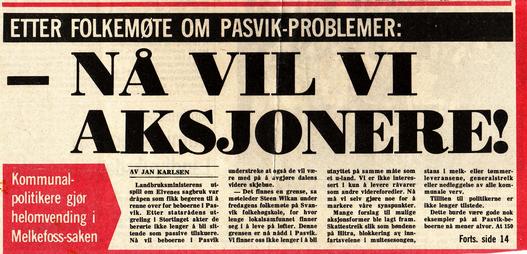

The Pasvik valley is rich in pine forests. Forestry was important for many people in the valley and has a long tradition. Before the last war, Pasvik Timber and Elvenes sawmill were large businesses. Since the area was protected, forestry operations have declined. ForestryMany of the older generation of the Pasvik valley worked in the forests. It was hard work, with hand-saws and axes, piece work and grinding toil. The men worked in teams, each with its own cook, and lived in log cabins. Reindeer and horses were used to transport the logs. In summer there were log chutes in some places that carried the logs down to the Pasvik river. Today, few people work in the forests. Some take out wood for fuel for their own use and for sale. Others build log cabins, saunas and stabbur (storehouses). These traditions are in the process of dying out. Ancient forestIn the Øvre Pasvik National Park, we find Norway’s largest remaining ancient forest. Pasvik’s ancient forest is the north-westerly offshoot of the world’s largest unbroken belt of evergreen forest, the Siberian taiga. Taiga simply means forest in the Yakut language, and the forest is characterised by deep pine woods, with some lowland birch, common birch, and Siberian spruce. The forest has been allowed to develop freely, without any great intervention from humans. Thousands of years of autumn storms and forest fires have created a varied forest with great differences in age among trees, and many trees are several hundred years old. Nature conservationConservation and protection of the forest has created a lot of local involvement and interest. Nature conservationists have fought to have the area protected, while others believe that Pasvik has contributed enough to protecting nature. Some people claim that nature conservation has helped destroy the basis for the forestry industry. Sawmill and planning millBetween the two world wars, there was great activity in sawmilling and the sale of timber and wood for fuel. The largest companies were Elvenes sawmill at the mouth of the Pasvik river, and Pasvik Timber at Jakobsnes, a few kilometres out in Bøkfjorden, which employed 250 people at the height of the industry. Many ships from the Continent made the long voyage to the north for timber, much of which was floated downriver from the deep forests of Finland. Both the state-owned sawmill and planing mill and Pasvik Timber struggled to make a profit right until the beginning of World War II. Pasvik Timber was bombed by German bomber planes in June 1940 and burned down. Elvenes sawmill was destroyed in the German retreat in 1944. Elvenes sawmillThe population of Pasvik were highly engaged in the hydropower development at Melkefoss. At the same time, the Elvenes sawmill affair arose. It was established by Order in Council in 1972 that a sawmill and a planing mill would be built in the Pasvik valley. Four years later, the Norwegian Agriculture Minister indicated different plans. This created unrest in the valley and the local people held a public meeting. Steen Wikan, who chaired the meeting, declared: “We will no longer tolerate being exploited as though we were an underdeveloped country. We are not interested in simply supplying raw materials for other people to process.”

|

Ancient forest in Øvre Pasvik National Park. (Photo: Erling Fjelldal, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

Map of protected watercourses and Øvre Pasvik National Park (green area). Forest conservation is creating debate in the local community. (Map: NVE)

Driving logs at the Sameti river in 1910. Approximately 3,000 logs were to be transported. Everyone in the valley used reindeer for various kinds of transport. For the people of the Pasvik valley, the pine forest was an important source of building materials and fuel, and a lot of timber was also sold to Kirkenes, Vadsø and Vardø. (Photo: Forest manager Arthur Klerck. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

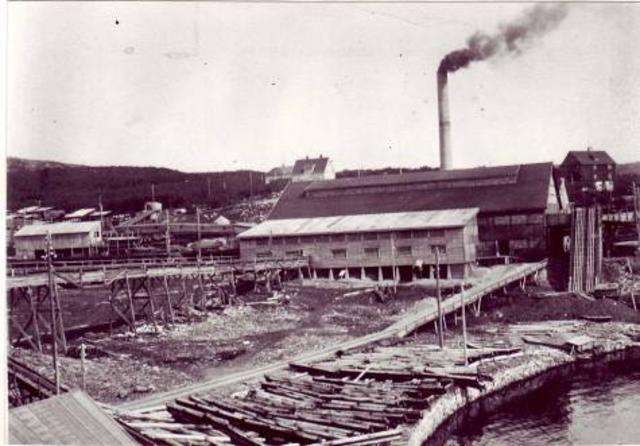

Pasvik Timber, not far from the mouth of the Pasvik river. The company was formed in Fredrikstad, and had agreements to supply timber from Finland. Some of the timber was sold to The Netherlands and England. (Photo: Unknown. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

The forest has been an important workplace for the people of the Pasvik valley. Today, few work in the forestry industry. (Photo: Jonas Endre Karlsbakk, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Forestry work. More modern equipment is brought into use. (Photo: Jonas Endre Karlsbakk, Sør-Varanger Avis)

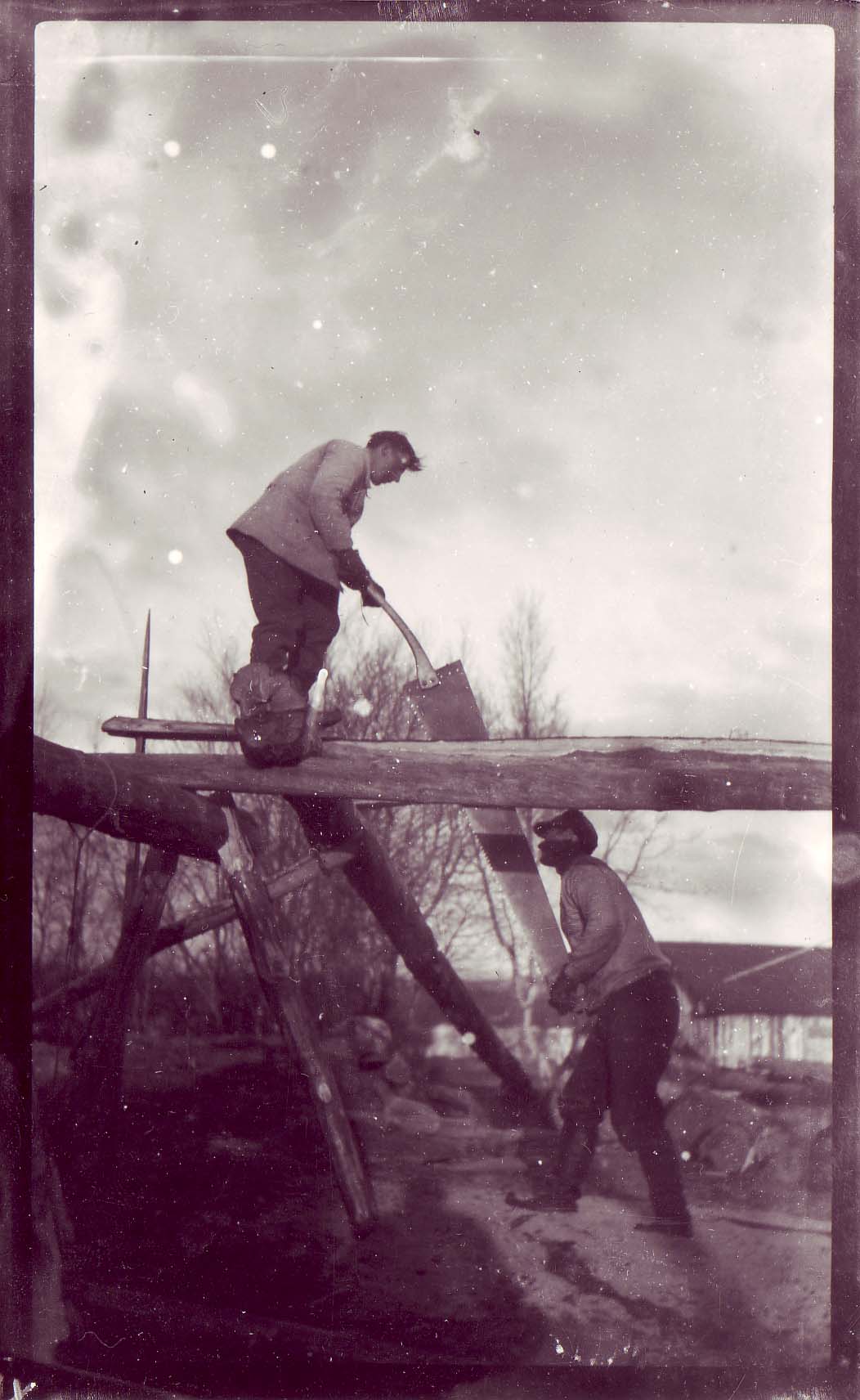

Two men, one log and one saw. Pasvik, spring 1923. (Photo: Sigurd Blix. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

River driving of logs in one of the falls in the Pasvik river before the war. (Photo: Unknown. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Elvenes before the war. Elvenes sawmill and planing mill stood at the mouth of the Pasvik river. (Photo: Unknown. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections) |

|

The Pasvik valley has a wealth of natural resources. The river has always teemed with fish, the forests are rich in fauna and flora, and there are plenty of wild berries. The people of the valley have always harvested what nature has to offer. The local population appreciate their closeness to nature. Use of natureThe Pasvik valley has been and remains rich in natural resources. People harvested more from nature’s larder than they do today; nature was important for people as a source of food. Fish in the river, lakes and tributaries provided food on the table. In the vast wilderness areas, trapping was also important for many families. Snaring ptarmigan and hare was common. Wild berries in the forests and marshes were picked by the tonne. Cloudberry-picking provided an extra income for many families. RecreationThe area between Finland in the west and Russia in the west is very large. The Pasvik valley is a popular place for nature-lovers. The local population in Pasvik use the area for food-gathering or recreation. There are many holiday cabins in Pasvik and people from the entire municipality use the area. Few municipalities have so many holiday cabins in relation to head of population as Sør-Varanger. In Pasvik there are many cabins along the river and the road.

|

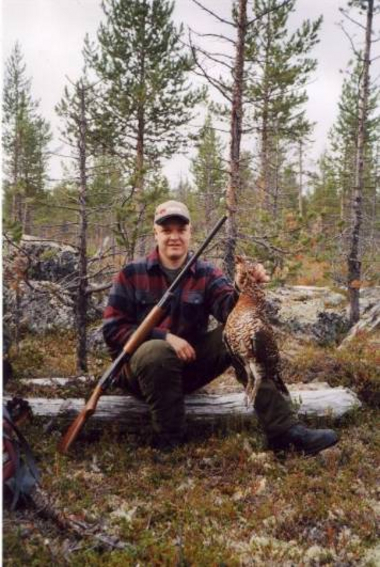

Hunting and fishingThe Pasvik valley is a popular area for hunters, with huge areas for hunting in. Stocks of ptarmigan and capercaillie vary from year to year, but many people are concerned that there is too much pressure on wildlife from hunting. You should be familiar with the area if you are to hunt there. The Pasvik forest is unpredictable even for the locals; the landscape is undulating and hillocky and not always easy to follow. The Pasvik river with its many species of fish is popular with both sport fishermen and ordinary anglers. The channels by the power stations at Melkefoss and Skogfoss are visited regularly by eager trout fishermen. Many people from the Pasvik valley use river boats to go after big trout. Some use nets to secure their catch of fish for the winter.

Pasvik berries. There are large areas of cloudberry marshes in the Pasvik valley. These cloudberries ripen earlier than the berries in the fjord areas. The Pasvik cloudberries are generally ready to harvest from the last week in July and onwards. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen)

Svein Runar Ingebrigtsen with a wood grouse. Hunting has increased in certain areas in recent years. Many are concerned about the stocks of wood grouse. (Photo: Elin Magga)

There is good soil for mountain cranberries in the Pasvik valley. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Dog sled driving has become more and more popular. (Photo: Tor Sandø, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Pasvik forest. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Winter sun. (Photo: Tor Sandø, Sør-Varanger Avis)

No trip complete without sausages cooked over the camp fire. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

Net fishing in winter is for tough guys only. (Photo: Mette Hallen)

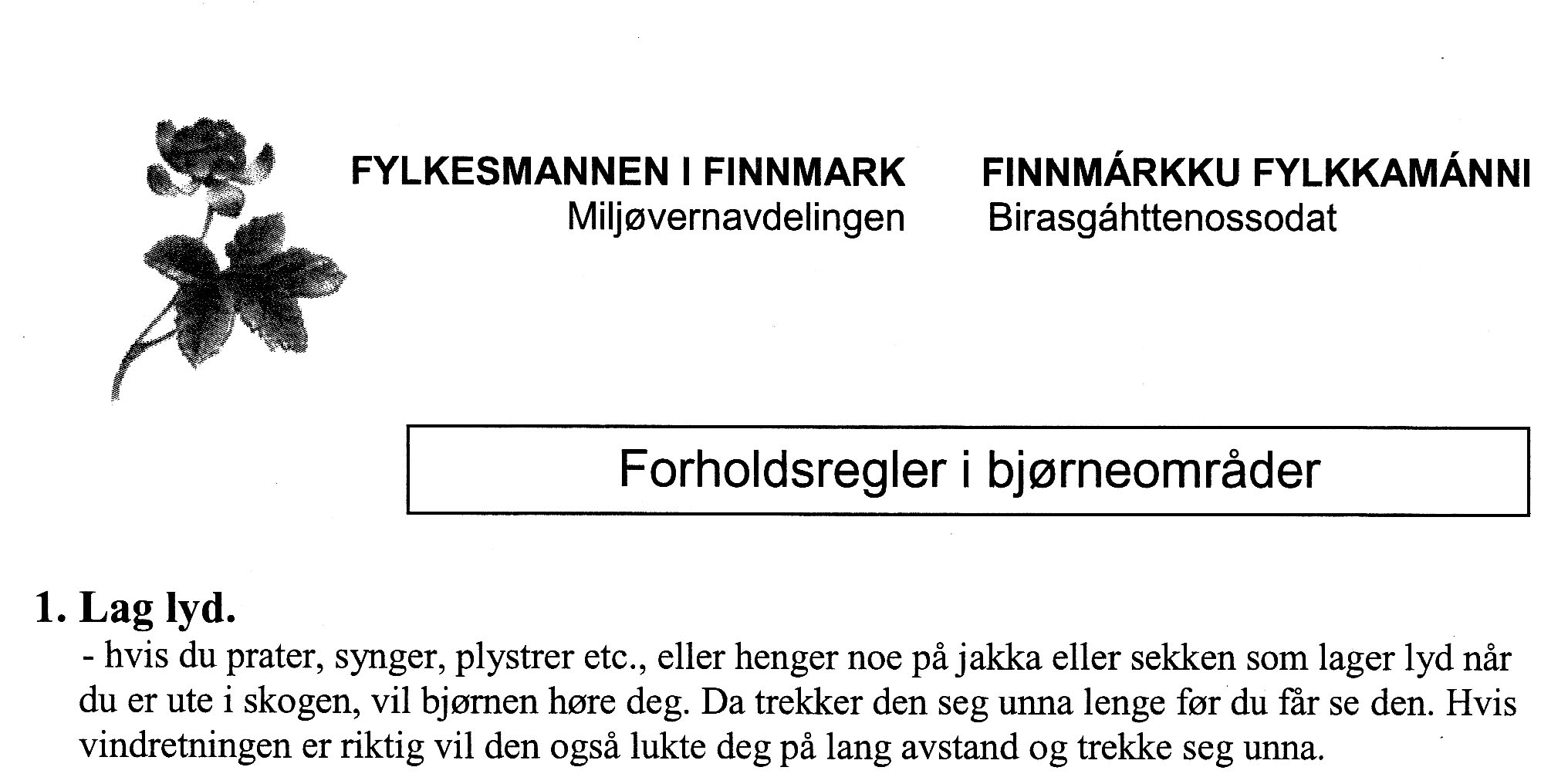

Bear alarm. The letter from the County Governor’s environmental protection department went out to all households in Sør-Varanger. |

|

The Pasvik river was the most important traffic route before the road was built on the Norwegian side and the waterfalls were dammed. People travelled by boat, reindeer and horse right up until the middle of the 20th century. The road through the Pasvik valley was finished in the 1930s. International school routeThe children in Pasvik went to school at Strand boarding school. For children living in Upper Pasvik, the journey to school was about 80 kilometres. The pupils spent 6-8 weeks at a time at the boarding school. There was no properly developed road network on the Norwegian side until the end of the 1930s. Before that, people had to travel by river boat, reindeer or horse; many also had to walk. When Finland was our neighbour in the east, the way to school was easier, as the Finns had built the Arctic Ocean Highway. The pupils in Upper Pasvik were transported over the river to Finland. Then they took the bus in Finland to Salmijärvi, after which they had to go down to the river before being transported or taking the ferry to Svanvik on the Norwegian side. Not many children have had their way to school go through another country! Road buildingThe building of the road through the Pasvik valley fulfilled several purposes. In the 1930s, the Norwegian government wanted new farms to be established in the border area. The network of roads was poorly developed and the road stopped at Svanvik. On the Finnish side, people were linked to the Continent. The Norwegian authorities were sceptical at times with regard to the close contacts with Finland. A road through the entire valley on the Norwegian side would improve conditions for those wanting to settle in the upper part of the Pasvik valley. Today, it is possible to drive by car all the way to Nyrud in the very south of the valley. Tram tracksWhen there were still waterfalls in the Pasvik river, it was necessary to build a system of tram tracks. These were rails that ran alongside the waterfalls and rapids that were not navigable by boat. This was absolutely essential for transport along the river. People had to get out of their boats and frequently help to haul them along the tracks past waterfalls and rapids. Transport on the riverThe people along the Pasvik river used the river for fish transport. Up until the Soviet Union became our neighbour after World War II, it was common to take a trip to visit neighbours on the other side of the river. Trade went on, people visited one another and had festive occasions together, and some rowed across to propose to their sweethearts. Ferry and local boatsWhen Finland was our neighbour in the east, there was a ferry that crossed to Salmijärvi. It transported cars, horses and goods between Norway and Finland. There was also a steamer between Svanvik and Langvannet south of Skogfoss. Regulated transportEveryone who travels by boat on the Pasvik river must have it registered with the Border Commissioner in Kirkenes, who awards a sign with a number and the Norwegian flag on it. If you cross the border in the river, you can risk being fined. The border guards keep a close watch. If you are on a fishing trip on the river, the nearest boat may be Russian. But in order to fish, you have to be a Norwegian citizen! WintertimeSnow scooters are popular for getting about in winter; there are more than 400 km of marked snow scooter tracks in Sør-Varanger. You can drive on the Pasvik river for many months in the winter, and in some places only a few metres from Russia. Dog sled driving has also become popular among the local people and tourists. |

Border marker in the river. It is forbidden to cross the border that follows the deepest channel in the river. The only exceptions are when the water level is low or in an emergency. (Photo: Tor Sandø, Sør-Varanger Avis)

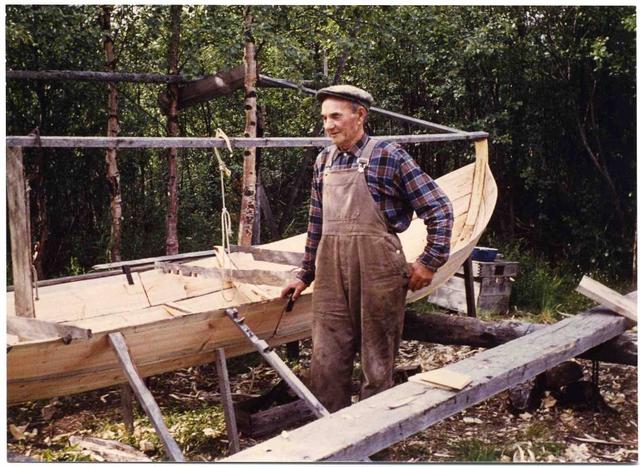

Ola Ranta was one of several craftsmen who made good river boats. The river people in the Pasvik valley have long boat-building traditions. (Photo: Olav Beddari)

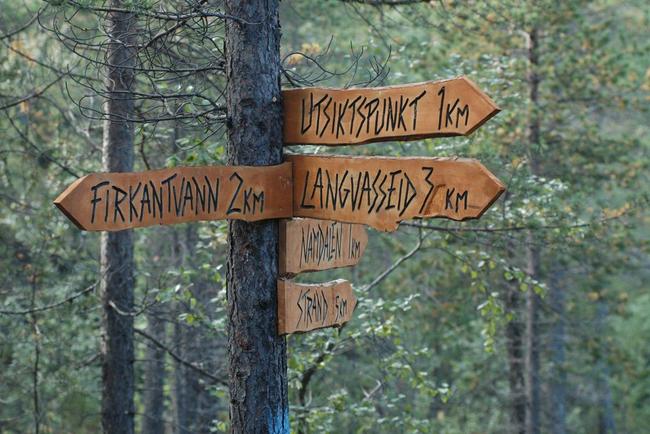

Marked paths are needed in the deep forests. (Photo: Tor Sandø, Sør-Varanger Avis)

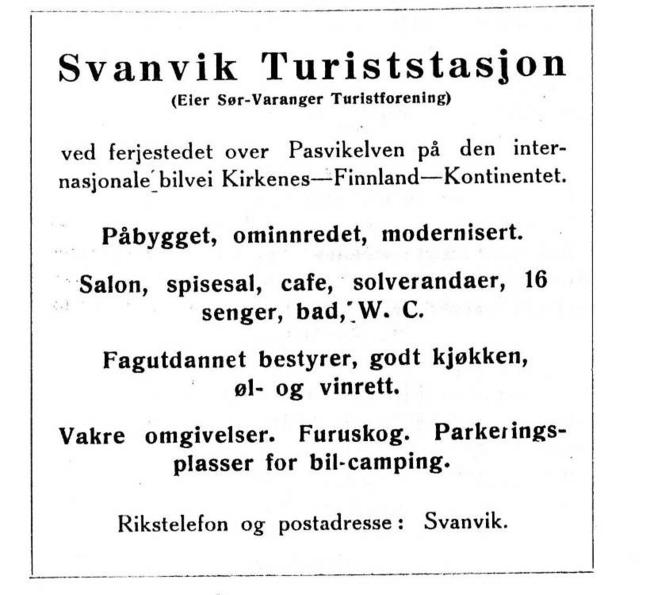

Advertisement from the magazine “Reise i Finnmark” (“Travel in Finnmark”) in 1939.

Information board at Brattli. It is wise to read it before travelling in the Pasvik valley. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

For anyone in doubt: the border does not go under water, but in the river itself. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

The state highway goes all the way to Nyrud in the south. There are also several logging roads. Some of the people of the valley want a road joining Norway and Finland. (Map: NVE)

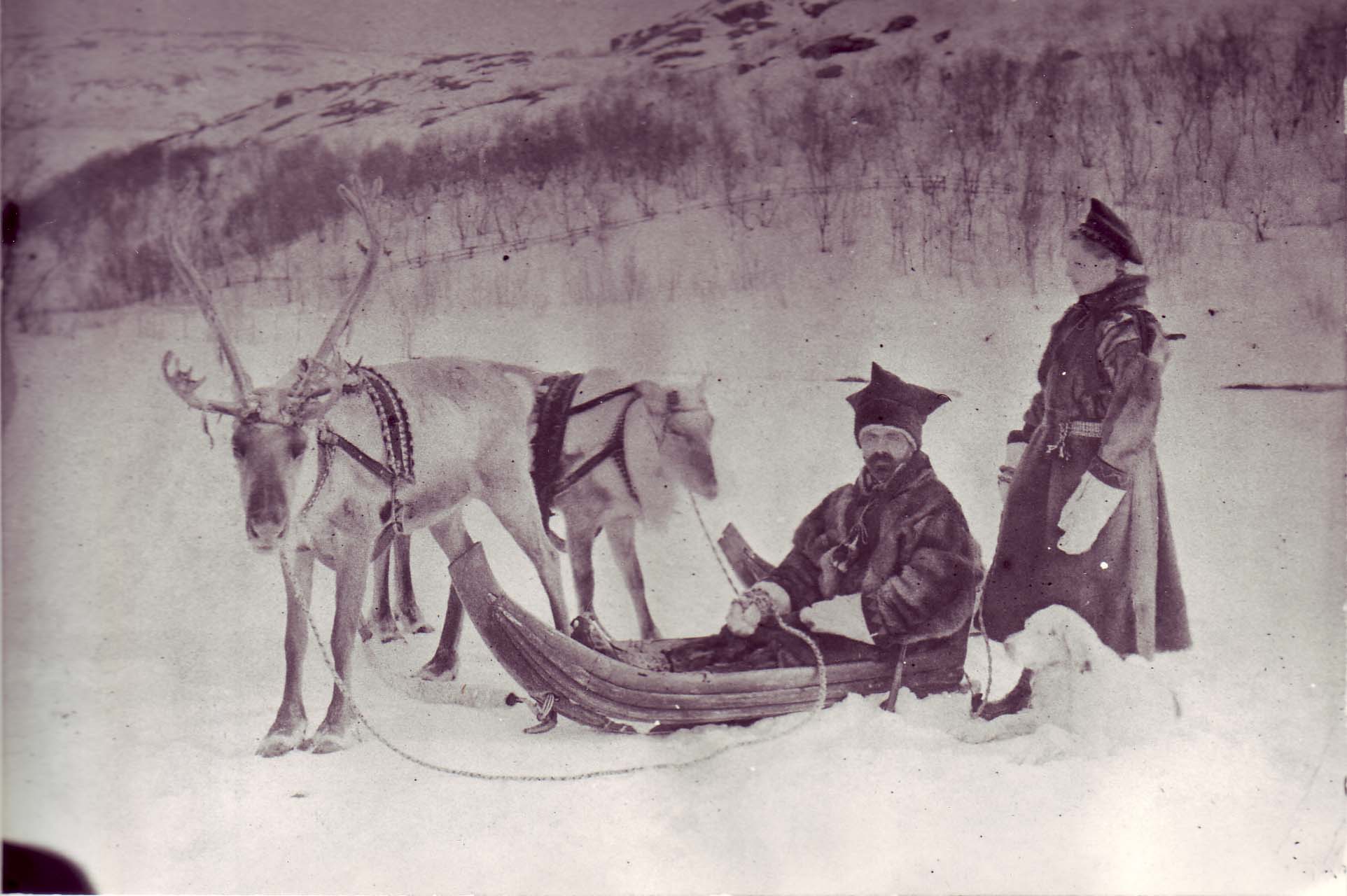

Parish priest Mads Le Maire and Lagertha with driving reindeer and sleigh. Reindeer were a very important means of transport well into the 1900s. (Photo: Ellisif Wessel. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Horses were important for carrying goods and people or as workhorses in farming and forestry work. Today equestrian sports have become very popular in the Pasvik valley. (Photo: Ellisif Wessel. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections) |

|

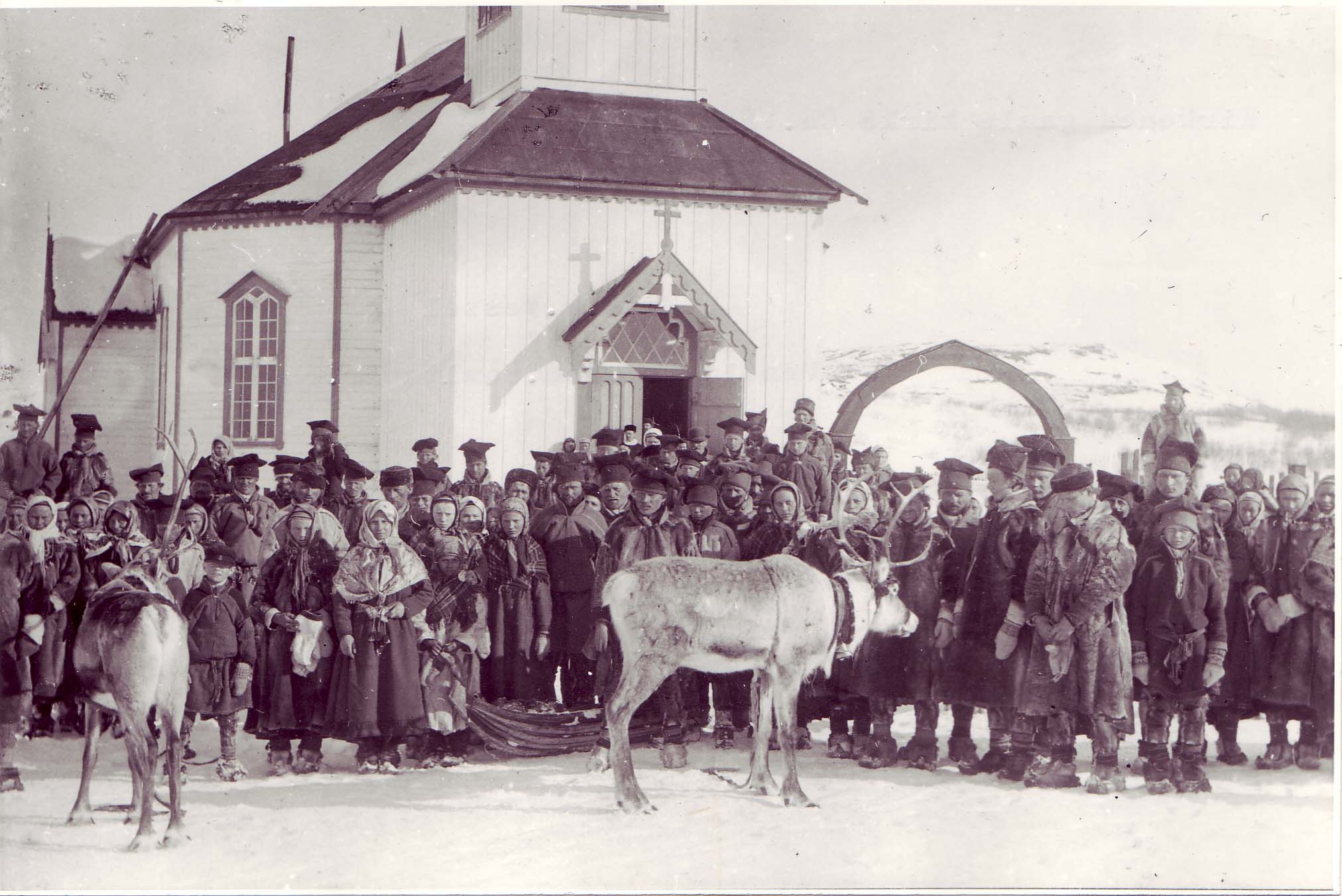

Sør-Varanger is a religious borderland where the old Sami nature religion, the Russian-Orthodox faith and the Lutheran faith meet. Nature religionThe old religion of the Sami is based on an animistic interpretation of life in which humans and nature were closely connected, inasmuch as all life, animate and inanimate, was held to possess a soul. It was important to stay on good terms with the powers of nature, and sacrifices to obtain good luck were made at sacred seid stones. Like the religions of other northern peoples, the Sami religion had a shamanistic form in which the noaide was the religious leader. The noaide mediated contact with the world of the spirits. In present-day Sør-Varanger there are two groups of Sami: East Sami and North Sami. The East Sami have inhabited the area for the greatest length of time. The North Sami are the descendants of the Sami who came to the area from the mid-1700s. Some of them were Sea Sami, or Nomadic or reindeer-herding Sami, and came from the most northerly and easterly parts of the North Sami area, around Tana and Varanger. The two groups had different languages, but could nevertheless understand one another. The biggest difference was in religion: the Sea Sami were Lutheran and the East Sami were Russian-Orthodox. Russian-OrthodoxThe East Sami came into contact with Christianity through the Roman Catholic church during the period prior to the Reformation, and via the Orthodox church in Russia. In the 1500s, the East Sami came under the Russian ecclesiastical system and judicial system. According to legend, the Russian monk Trifon christianised the East Sami and built St. George’s Chapel in Neiden and the chapel in Boris Gleb. The Pasvik Sami were a religious people, and maintained the rituals of the Russian-Orthodox church to the extent possible. Mass is still held in St. George’s Chapel in Neiden.

LutheranOnly sporadic attempts had been made to christianise the Sami prior to the beginning of the 18th century, when the priest Thomas von Westen carried out several major missions to the Sami areas. The Sami mission led to a decisive break in continuity in the centuries-long Sami religious tradition, which was forced underground, if not forgotten. As opposed to the Russian-Orthodox East Sami, the North Sami became Lutherans. In 1862 the Lutherans in the municipality got their very first church when Sør-Varanger Church was consecrated. Churches as border markersPoliticians frequently pointed to the importance of marking Norwegian sovereignty in the area. Churches and schools were important partners in this task. In Sør-Varanger three church buildings were erected which were intended not only to serve ecclesiastical needs, but also to provide spiritual and physical protection for the border to the north-east.

Strand boarding schoolThe establishment of boarding schools was an initiative which was part of the process of making Finnmark into a homogenous Norwegian area. In Sør-Varanger people lived spread over wide areas and it was therefore difficult to have a permanent school in each district. Strand boarding school in the Langfjord valley was built in 1905 and was a combined school and church. As there was no church in the local area, one of the classrooms was fitted out to enable it to be used for church services. A churchyard was also established close to the school. |

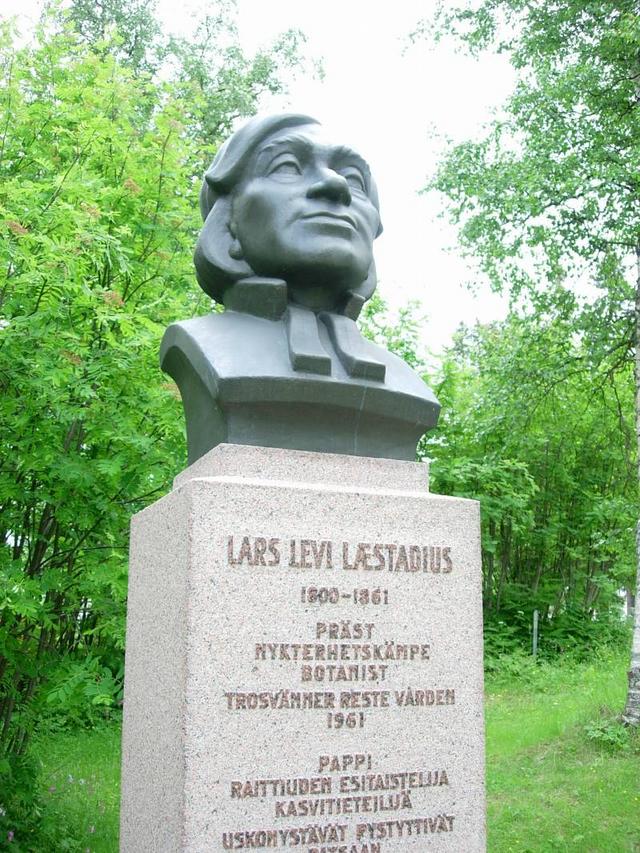

LæstadianismLars Levi Læstadius (1800-1861), who was the priest in Karesuando in Sweden, initiated a revivalist movement which gradually spread through large parts of Norway and Sweden and most of Finland. For Læstadius, an extremely important cause was the fight against alcohol. He also opposed all forms of unnecessary finery and splendour, which he believed distracted people’s attention from God. In Sør-Varanger, the revivalist movement was initially concentrated around Bugøyfjord and Bugøynes, but quickly spread further afield. By around 1885 most of the Finnish and Sami population had joined the movement, while the Norwegian population to a great extent remained faithful to the Church of Norway.

The island of Ukonkivi in the Inari lake. The island has been considered sacred for centuries, and was used by the Sami as a place of sacrifice to ensure a good hunt. Food, birds, precious stones and animal horn were offered in sacrifice. Ukonkivi is one of 3,318 islands in the lake. (Photo: Riina Tervo, Metsähallitus)

Father Johannes during the annual service held at St. George’s Chapel in Neiden. Many Orthodox pilgrims make the journey to Neiden, Nellim and Sevettijärvi to attend the religious ceremonies. (Photo: Yngve Grønvik, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Bishop Panteleimen from Oulo blesses the water in the Neiden river by St. George’s Chapel. (Photo: Yngve Grønvik, Sør-Varanger Avis)

The chapel in Nellim, Finland. Many of the East Sami who belonged to the Pejsen siida (the Petsamo siida) chose to move to Nellim after Finland was obliged to surrender the Petsamo area to the Soviet Union after World War II. Many East Sami have maintained their Orthodox faith. (Photo: Sigrun Rasmussen, Savio Museum)

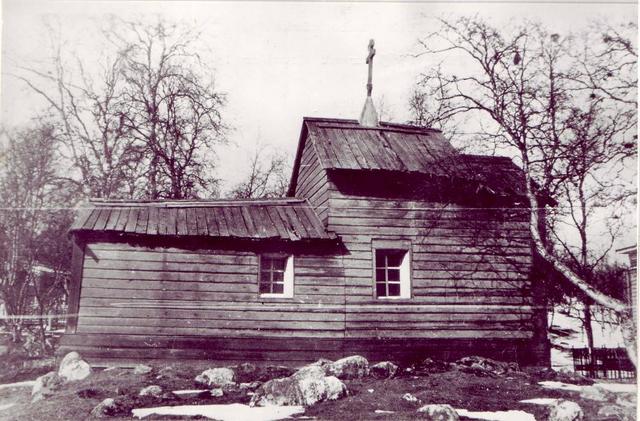

The old Boris Gleb church, which was consecrated on 24 June 1565. For the East Sami in the Pasvik siida, Boris Gleb was important as a settlement and a religious meeting place. Unfortunately, the old church was burned down in October 1944. (Photo: Ole Rugås. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections)

Stone monument to the preacher Lars Levi Læstadius in Pajala, Sweden. Læstadius’ teachings won favour with large numbers of Finns and Sami living in the North Calotte (the Arctic area of the Nordic countries and the Kola Peninsula). Læstadius believed that the word of God should be preached in the people’s own language. The Church of Norway was worried about the enthusiastic response to Læstadius’ teachings and thought it was necessary to build churches in areas where Finns and Sami lived. (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen)

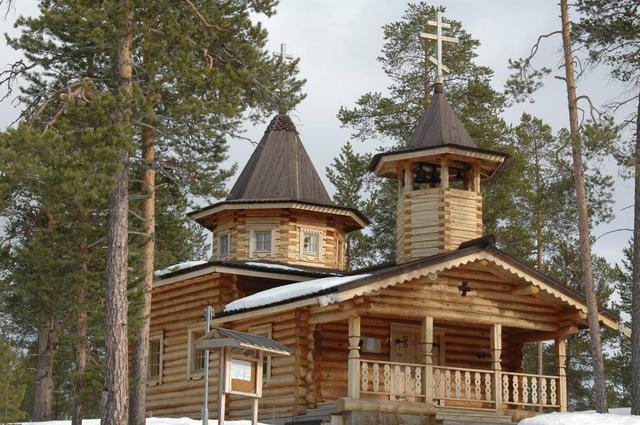

Svanvik Chapel in the Pasvik valley, consecrated on 25 September 1934. The Church of Norway and the Norwegian state marked their presence in the border area. The magnificent timber building is visible evidence of good Norwegian building traditions. (Photo: Ingar G .Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Trifon’s Cave is not far from the mouth of the Pasvik river. It was the custom of the East Sami to leave some coins in the cave before going out onto the fjord to fish. The cave is most easily accessible at low tide. The high tide mark can be seen on the mountainside. (Photo: Gry Andreassen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Outside Kirkenes Church after a service in the 1890s. The clothing and footwear show that Sør-Varanger’s Sami population were well represented also in church life. While the East Sami belong to the Russian-Orthodox Church, most North Sami have been attached to the Lutheran Church or Læstadianism. (Photo: Ellisif Wessel. Sør-Varanger Museum Collections) |

|

Through the centuries, the Pasvik valley has been a meeting place for different cultures and peoples. Traditions have merged and developed over time. Today there are many cultural offerings for all age groups. Cultural life and traditionsThe Pasvik valley is a meeting place for different cultures. The people have learned from one another and benefited from one another’s knowledge. Many traditions have been carried on and developed further. Raw ingredients like fish, meat and berries are used in new variations, although still based on the old knowledge. There is a long tradition of using hides from reindeer, cattle and sheep, and skin from fish. The people of the valley have exploited the resources offered by nature. Craft traditions from Norwegian, North Sami, Finnish and East Sami cultures are maintained by home crafts associations and individuals. The Pasvik valley’s roots are clearly visible if you take a trip to one of the local cultural days or Christmas markets. The schools are important as culture-bearers and there is a great deal of interest in local history. Many children learn Finnish and Sami at school. Contacts with our Russian and Finnish neighbours are attended to through various collaborative projects. |

Band practice in Pasvik. The valley has its own marching band which joins in celebrating Constitution Day on 17 May. (Photo: Jostein Jacobsen, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Schoolchildren from Pasvik School outside Strand boarding school. Strand is now owned by Sør-Varanger Museum. The museum has had several collaborative projects with the schools in Pasvik. There is much interest in local history in the valley; few places in Norway can have so much history per head of population! (Photo: Ingar G Henriksen, Sør-Varanger Museum)

Offroad through the deep forests. (Photo: Anne Mette Bjørgan, Sør-Varanger Avis)

The legendary Swedish goalkeeper, Thomas Ravelli, signs autographs at the Pasvik International Tournament. The tournament and football school are organised annually by Pasvik Hauk, and children come from Norway, Finland and Russia to take part. Several hundred children gather each year for this border country event. (Photo: Tor Sandø, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Pasvik valley school choir. Children from Pasvik and Skogfoss schools. (Photo: Tor Sandø, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Russian folk music performed in the Galleri Pasvik at Svanvik. Contact with Russia is many-faceted, and music has an important place. The gallery holds regular exhibitions. (Photo: Anne Mette Bjørgan, Sør-Varanger Avis)

The Pasvik Trail, an annual dog race through the Pasvik valley. (Photo: Jonas Endre Karlsbakk, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Land Day at Svanvik, 2004, with old tractors on display. Many people are involved in farming in the Pasvik valley. (Photo: Jonas Endre Karlsbakk, Sør-Varanger Avis)

Trotting race at Pasvik trotting park. (Photo: Jostein Jacobsen, Sør-Varanger Avis) |

|

East of Finland and west of Russia lies the Kingdom of the Bear - Pasvik. Here, where the three countries meet, bears cross the border pretty much as they wish. The Pasvik valley is home to the largest population of bears in Norway and rare species that are not found in the rest of the country. The wilderness and predatorsPasvik is only a small part of the vast areas of wilderness that stretch into Finland and Russia, and here one may encounter all of the four big predators: bear, wolf, lynx and wolverine. Although the bear population belong in all three countries, the Pasvik valley has a permanent population of animals, frequently with a number of she-bears breeding here. Lynx prefer the conditions further out towards the coast, while wolves enter the area as dispersal-resident animals from our neighbouring countries. Wolverine were previously threatened by hunting and trapping, but the population has increased in recent years. Elk and bearAt the beginning of the 1900s, elk were rarely seen in the forests of Pasvik, and it was not until 1924 that the first known elk was shot in Sør-Varanger. Today, there is a large population of elk, and in the spring they provide an important source of food for bears. Particularly when the snow begins melting in spring, and its surface is so hard that the bear “floats” on top of it but the elk goes through, the bear has an important advantage over weak elk calves and pregnant females. Northern most limitThe elk population in Pasvik is one of the most northerly in the world, and for many species this is the northernmost limit of their habitation. There is a small population of roe-deer here, although Pasvik’s climate is the most extreme in which roe-deer can survive. The area is also home to species which find their westernmost limit here. One such species is the raccoon dog, which is rarely found further west in Norway. Pasvik’s ancient forestThe ancient forest in Pasvik is the last great ancient forest in Norway, and is the north-westerly offshoot of the world’s largest unbroken belt of evergreen forest, the Siberian taiga. The ancient forest has been allowed to develop freely, and has to a great degree been protected against intervention from humans. Thousands of years of autumn storms and forest fires have created a varied forest with great differences in age among trees, and many trees are several hundred years old. Birds in the ancient forestOld and dead trees provide nesting places and food for many of the birds of the ancient forest. The three-toed woodpecker finds its favourite food, the bark beetle, in dead pine trees, and the old pine forest provides the grounds for the male capercaillie’s distinctive mating games. Some owls prefer to make their nests in natural hollows in old trees. The hawk owl is the most common owl in the forest, while the Lapland owl is the most exotic. The role of small rodentsSmall rodents, such as the red-backed vole and the grey-sided vole, are favourite prey for owls and a number of the forest’s animal and bird predators. Small rodents reproduce quickly, and can therefore appear in extremely large numbers. The population density of small rodents fluctuates, and in Pasvik numbers peak about every five years. There is often a large population of ptarmigan in years with many small rodents, because fewer ptarmigan chicks fall victim to animals and birds of prey. In years with few small rodents, the pressure on ptarmigan chicks is much tougher.

|

MuskratMuskrat is a new species in the Pasvik river system. Muskrat were set out in the wild in Finland and Russia in the early 1900s, and during the 1970s they spread further to Sør-Varanger. The muskrat is not actually a rat as its name might indicate, but a small rodent. The North American Indians called it «the beaver’s little brother» and the two animals are not dissimilar, although the muskrat is much smaller and its tail is flattened from the side.

Bears prepare to hibernate for the winter as the first big snows arrive. They hibernate in order to avoid a time of year when it can be difficult to find food. Bears can remain in their winter lairs for 5-7 months and the she-bear gives birth to her cubs there. The cubs are surprisingly small at birth: weighing about 300-500 g and about 25 cm long. When spring comes and it becomes easier to find food, the bears leave their winter lairs. By the time the cubs hibernate again in late autumn, they will have put on up to 30 kg! (Photo: Steinar Wikan, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

Mapping of the bear population in Pasvik is done by tracking and visual observations, and researchers have now also started studying bear droppings. Svanhovd Environmental Centre has been inspired by the methods used by criminal investigators and is now using DNA analysis. Bear droppings contain the bear’s DNA, and DNA analysis reveals the bear’s identity, kinship and sex. This method provides a good insight into how many bears there are in Pasvik. (Photo: Paul Aspholm, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

The elk population in Pasvik is unusual. Some of the animals have annual migrations where they cross the border between Norway and Russia: these animals are often called "migrating elk" or "Russian elk". Migrating elk prefer the good summer pastures on the east side of the Pasvik river, between the Russian protective fence and the border. Winter grazing is better in the pine forests on the Norwegian side, where the elk feed on pine sprigs and bark. (Photo: Steinar Wikan, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

The Siberian jay is an inquisitive bird which, with its trusting nature, is often a pleasant acquaintance for ramblers in the area. It often sweeps in on silent wings and can be remarkably mute; when it does utter a note the Siberian jay’s song is low-voiced with a mewing sound. (Photo: Morten Günther, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

The grey-sided vole is the most common small rodent in Pasvik and can reproduce at a tremendous rate. It can be sexually mature at about three weeks old, and after a three-week pregnancy it can have up to five or six young. The female often becomes pregnant right after giving birth, so that the next litter can be produced while she is still suckling the new babies. A grey-sided vole can thus produce thousands of descendants in one season. (Photo: Ragnar Våga Pedersen, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

Wood grouse or capercaillie, both the male and female birds, are closely attached to the old pine forests in Pasvik, and in the wintertime pine sprigs and shoots provide a large part of their food. This makes quite a poor diet, and in order to get enough nutrition wood grouse spend a lot of the day eating. In cold periods they remain inactive for large parts of the day, and if the temperature becomes extremely low they may even stop eating altogether. (Photo: Steinar Wikan, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

The young hare lies quite still, pressing its body to the ground to avoid being seen. In winter, the hare changes to a white camouflage coat, which makes it difficult for predatory birds and animals to spot it against the white snow. (Photo: Morten Günther, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

The Lapland owl is one of the world’s largest owls. It is rare, but is seen more often in Pasvik than in the rest of Norway. It is a sporadic visitor, however, in some years appearing in several places in the valley and other years not appearing at all. The Lapland owl has a nomadic way of life, moving around looking for areas where there are plenty of small rodents. (Photo: Steinar Wikan, Svanhovd Environmental Centre)

Roe-deer are a new addition to the fauna of Pasvik, having arrived here along the coast from the west. In the winter of 2005 there was a small group of six animals in the valley: a buck, a calf and four does. Pasvik is right up at the northernmost limit for roe-deer populations. Winter here can be hard for the animals and they are often given a helping hand to survive by feeding them. (Photo: Steinar Wikan, Svanhovd Environmental Centre) |